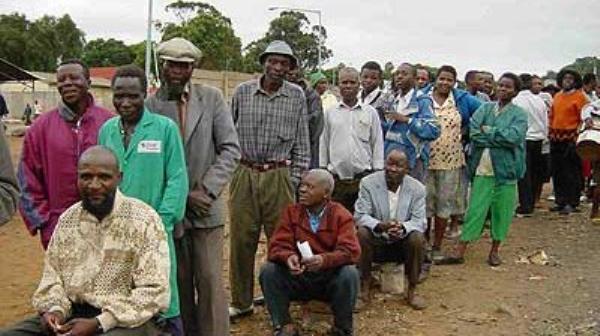

In Zimbabwe, as South African President Thabo Mbeki continues his efforts to mediate between government and opposition, President Robert Mugabe has set a date for elections - presidential, parliamentary and council - of 29th March. Zimbabwean Jesuit, Dominic Tomuseni, reflects on whether this might be a moment of hope for a troubled country.

At the end of March, Zimbabweans will go to the polls to elect new leaders. Given the current situation and the history of elections in Zimbabwe in particular and in Africa in general, one wonders if it is worth any attention. The post-election experience in Kenya has left many doubting whether Africans are capable of any democratic process. The ANC elections in South Africa act as a response. It is a good example of how people of different convictions can belong to the same camp. So Africa is not hopeless. What follows are reflections of hope. Things could be better in Zimbabwe. They should be better. Nonetheless, not all is lost and all is not lost. By this I mean that a lot has been lost, but there is still a lot at stake. Elections might not bring the expected results. They will not restore the economy to where it was, but they are a moment of taking stock at different levels, statistically and semantically.

The history of elections in Zimbabwe is full of dramatic and tragic events. The 1980 elections that ushered in majority rule eclipsed the minority gains. Joshua Nkomo’s Zapu PF won a significant minority – 20 seats out of the 80 which were up for grabs. They were not given a fair share of the national cake and the result was the Matebeleland crisis and the death of many innocent people. Bishop Muzorewa had an insignificant three seats and Ndabaningi Sithole only one. They eventually fell into oblivion, relegated to the dustbin of history. Sithole’s contribution to Zimbabwe’s liberation was not recognised when he died. In 1985 there was no significant opposition, and the one possible great challenge was denied a forum. Individuals have arisen and offered the prospect of change. In 1990, the Zimbabwe Unity Movement arose and caused a stir but it won a few seats and then disappeared. Margaret Dongo, who entered as an independent in 2000, made history by becoming the first candidate to challenge the results in court: they were nullified and she went on to win the re-run election. Jonah Moyo, like Dongo, left Zanu, stood as an independent, and won his seat. Sithole secured a seat in his home area for a long time. The greatest challenge was in 2000 when the Movement for Democratic Change lost by a narrow margin. They won 57 of the 120 seats, but were still unable to oppose the government effectively in parliament.

What is emerging in this brief account is that Zimbabwe has operated as a majoritarian dictatorship, in which the winners take all. This has not been helpful. Politicians like Moyo and Sithole have been faithful to their own, but if they had been part of the government, the areas they represent would have been paid more attention. The 2000 elections showed a great divide between urban and rural areas. If the MDC had been given a chance to operate in government then the concerns of those in the urban areas could have been addressed. Cooperation at that level could have helped to diffuse tension at the grassroots level. Thus, as we enter into the 2008 elections, if they are to work at all, what matters most is how to incorporate the minority.

Another big question with the 2008 elections coming up is what alternative is there, or how much of an alternative is possible? This is a question very much linked with what has been said about giving room to the minority. There are names floating in the air, but what we hear about them is mostly speculation, coming mainly from the foreign press, which is regarded with suspicion by many voters. The challenge here is to be tolerant and give space and room to the opposition to share what they have to offer. How far this is possible in the time left before the elections is a big question, but it is not too late to start reflecting on it now.

What has been discussed so far only touches on those who will be elected. The big question is about the voters themselves. Apart from their experience, what else is available to them to make an informed choice? Voter education has been frowned on because it is associated with indoctrination. But we need to open more forums for discussion if voters are to know what they are voting for. Is all of that possible on the eve of the elections? Maybe not, but open discussion is not only necessary before elections - it should go on after them too.

I do not hesitate to point out that these things – which I suggest are necessary conditions for an election to work in Zimbabwe – have been missing. Thus I am not looking forward to much change in this election. However, I have hope in the people of Zimbabwe. Their resilience and love for peace is exceptional. Things have happened to them that, when they happen elsewhere, would constitute a crisis, yet they have dealt with them in a calm way. We will go to the polls and express our choices. We might be disappointed, but life will go on. It is in this milieu that suggestions such as mine will become relevant.

Dominic Tomuseni is a Zimbabwean Jesuit currently studying theology at Heythrop College, University of London.