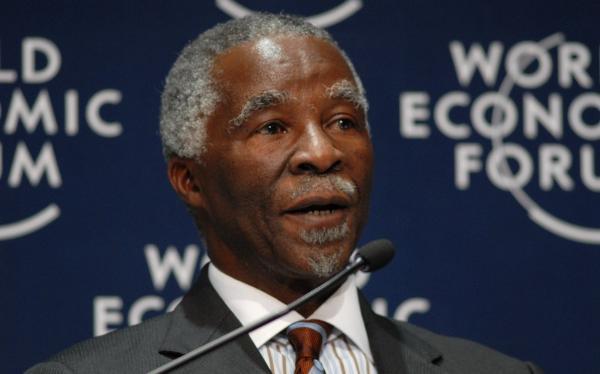

After Thabo Mbeki confirmed on 19th September that he would be stepping down as President, what lies ahead for South Africa? Chris Chatteris SJ examines the current political climate in South Africa and looks at the challenges and implications of the next presidency.

“South Africa belongs to all who live in it, not to any political formation, however powerful.” So protested Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, expressing his deep sense of unease about the manner in which President Thabo Mbeki was removed from the highest office in the country. “Our country deserves better” he said, adding, “I am deeply disturbed that the nation ... has been subordinated to a political party”.

Strong and ominous words from a powerful prophetic voice, but unfortunately one which is likely to resonate only with an older, more courtly generation of ANC (African National Congress) members. That there has been a political shift accompanied by a generational and cultural change in the ANC, was made clear at the party conference in Polokwane at which Thabo Mbeki lost the Presidency of the organisation to his corruption-accused challenger and one-time Vice President of the country, Jacob Zuma. Mbeki's biographer Mark Gevisser reminded us on television of a low point at that conference where Mbeki stood before the assembled delegates and with rather reckless courage, accused this new generation of being 'howlers' and not understanding the true tradition of the organisation, a tradition of reasoned, inclusive debate.

The dignified manner of Mbeki's stepping-down from power has been an example of this older culture. However Mbeki and his supporters have been unable to prevent the ascendancy of the new ethos, embodied by the inflammatory utterances of a young Turk, ANC Youth League leader Julius Malema with his now famous mot that he was ready to 'kill' for Jacob Zuma.

Ironically, however, it was a venerable white judge, a man with impeccable 'activist' credentials who had once defied the apartheid state's attempt to arrest Archbishop Hurley, who was Mbeki's ultimate nemesis. In one of the numerous legal actions to do with Zuma's corruption case, the judge ruled that the elite National Prosecuting Authority (the 'Scorpions'), had rendered their attempts to convict Zuma invalid thanks to procedural errors brought on by an excess of zeal.

However, the judge went further and suggested that there was 'merit' to the view that the state, in the persons of the Minister of Justice and her predecessor, had interfered politically in the case, the implication being that Mbeki's hand was also discernible in this. For good measure he cited other cases in which there appeared to be political meddling, in particular the protection apparently given to Chief of Police Jackie Selebi who has admitted to being a personal friend of a notorious racketeer.

Judge Nicholson was listing these cases to ensure the independence of the judiciary in a young democracy and many have applauded him. However, the inference of political interference left Thabo Mbeki desperately exposed. His enemies in the Zuma camp have long made this accusation of political manipulation of the criminal justice system. Their vindication by such a sober figure of the legal establishment resulted in a gleeful 'we told you so' chorus and an almost immediate decision among those who now call the shots in the ANC to 'recall' (i.e. sack) Mbeki, a decision later upheld by a full meeting of the ANC's 100-strong National Executive Committee. Much to their relief he spared the party the disedifying spectacle of a parliamentary impeachment by tendering his resignation when it was demanded.

So who are these new shot-callers in South Africa's most powerful political organisation? They are Messrs Gwede Mantashe, the Secretary General of the ANC, Zwelinzima Vavi, the leader of COSATU (the trade unions federation), Blade Nzimande, the General Secretary of the South African Communist Party, Julius Malema, the Youth League leader, and Ms Baleka Mbete, the Speaker of Parliament. They represent, at least in theoretical ideological terms, a left-wing tendency.

The Communist Nzimande might strike the non-South African reader as an odd man out. Not at all. There has always been an arrangement whereby Communist Party and ANC members could have dual membership of the two organisations. The strength of the ANC during the time of struggle was precisely its extremely broad-based appeal. However, what was appropriate in the struggle against apartheid is now proving to be an Achilles heel in an era of normal politics.

Herein lies the structural problem which is presently exacerbating the nasty battles between personalities bedevilling the African National Congress, which in some local branches has even led to the drawing and using of knives and guns. In a post-liberation struggle African country, normally the only viable way to power has been through the liberation-movement-turned-political-party. The grip on Zimbabwe of Mr Mugabe's ZANU-PF illustrates this perfectly. In other words, anyone outside the ANC who hoped to gain any real political influence within twenty-five years of the end of apartheid was living in cloud cuckoo land. Jacob Zuma described this political phenomenon rather well when he said that the ANC would rule “until Jesus returned”. Since Jesus has not yet returned, it is therefore still the case that anyone interested in real power has to belong to the ruling party and those that dominate the ruling party are power brokers among the powerful.

For that reason the great prize in South African politics is the domination of the ANC. That is the game behind all the rather confusing political events of late. To put it simply, Mbeki and his more centrist and economically conservative tendency in the ANC has been ousted by Zuma and a more populist, left-wing tendency, probably for the usual mixture of motives – ideology, ambition and vindictiveness. Some have called it a coup, some regicide, and others have likened it to the removal of Margaret Thatcher in 1990.

The takeover was made possible by something that was inevitable – a sense of let-down for a people with huge expectations. After 14 years of freedom from apartheid, although the economy has grown more strongly and consistently than at any time since the Second World War and many 'previously disadvantaged' (read 'black, coloured and Indian') people have benefited, there is still a substantial underclass living in shacks, often without jobs or the education necessary to get them. These people are the natural constituency for a more populist leader, one who has the common touch, an entertainer, always happy to give a performance of his trademark struggle song Leth' uMshini Wami (‘Fetch my machine gun’).

The song is a hit among this deprived class because of its allusion to the struggles of the past, which for them have not gone away. It also has that hint of menace, reminding the Mbeki people of the continuing importance of liberation credentials. The historical point here is that while Jacob Zuma was head of intelligence for Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the ANC, Thabo Mbeki was an 'exile', an activist for the ANC in the more comfortable confines of places such as London. This 'internal/external' division in the history of the ANC's struggle is another faultline underlying the present political schism.

The question of tribe or ethnicity comes into play, but perhaps more subtly than at first appears. Jacob Zuma is from the majority Zulu group and the Zulu rural heartland and therefore is as his supporters put it on their T-shirts a '100% Zulu Boy'. He is also a traditionalist and polygamist. All this says loudly and clearly that, despite Chief Magosuthu Buthelezi's attempt to corner the Zulu political market in Zuma’s home province of KwaZulu-Natal, the ANC is alive and well in that region, so much so that it can even produce a South African president. There are implications for the local, provincial politics of a Zuma presidency and they bode very ill for Buthelezi and his Inkatha Freedom Party.

This does not mean that Zuma's support base is only among the Zulus. The power-brokers mentioned above are themselves a mixed ethnic bag and their calculation is that, as a populist, Zuma will command political support across the South African board, particularly among the disaffected and excluded. This is probably correctly calculated. If the constitution permitted a direct presidential election then some observers believe that Zuma would easily defeat Mbeki. Not that there is an electoral threat to the ANC. However, some party insiders worry that the next election might bring a stayaway protest among ANC voters who have lost hope of the party delivering on their dreams. The hope is that Zuma will galvanise these people into voting again.

Parliament is the electoral college for the president and its overwhelming ANC majority will do the party's bidding and elect Zuma in due time. For the moment it has accepted Mbeki's resignation and has voted in as Acting President Kgalema Motlanthe. He is a temporary olive branch to Mbeki supporters, an intelligent, courteous conciliator of the old school, not a populist, but with roots in the trade union movement which has backed Zuma. Though a Zuma man, it is hoped that he will be able to reach out and heal some of the wounds caused by the recent blood-letting.

Come the general election next year, assuming nothing radically untoward intervenes, Zuma will be voted in as President by Parliament after a resounding or not so resounding ANC victory at the polls. Zuma will have his problems as President and this interim period will give him time to reflect on them. Firstly there is his image, particularly in the eyes of the international community. He still stands accused of corruption in the arms case. Judge Nicholson specifically stated that his judgement did not pronounce on the question of guilt or innocence. Zuma's lawyers were hoping to work for a permanent stay of prosecution. However this has been complicated by the National Prosecuting Authority's decision to appeal against the Nicholson finding. It seems inevitable that during his five years in power he will be continually haunted by courtroom dramas, always pointing back to the question of the arms deal.

Zuma also has to live up to the Mandela-Mbeki legacy. We have moved from political saint (Mandela) through philosopher-king (Mbeki) to a corruption-accused populist entertainer with hardly any formal education (Zuma). Certainly there is the feeling among more middle class sections of South African society that the ANC could surely have produced a better leader from their talented ranks.

He will also have to deliver on his populist promises. The people on the left, particularly COSATU, the trade union congress, and the Communists will be watching him closely to ensure that his economic policy is to their liking. Here he has a very small margin of manoeuvre between the unions and the businesses; one of the really big questions is whether or not he will retain the services of Mbeki's Finance Minister Trevor Manuel, who is the darling of business and therefore not popular on the left. And if the world economic situation is cruel to him, he could default badly on the implicit deal with the poor and unemployed that his election holds to.

Even Zuma's critics express hope for some positive spin-offs from a Zuma presidency. Because he is close to the trade unions who are close to Morgan Tsvangirai of Zimbabwe, the likelihood is that Mugabe's endlessly spun-out, Rasputin-like exit from the political stage will be hastened. Motlanthe is also in the unions' camp, so that process might conceivably start before Zuma takes the reins of power.

Another hope is a change in the government's view of HIV/AIDS, bedevilled by Thabo Mbeki's apparent questioning of the link between the virus and the disease, a stance seemingly imitated by his highly unpopular health minister Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, she of the famous diet of garlic, beetroot, olive oil and African potatoes. After his own horrible gaffe in his rape trial where he said that he took a shower after intercourse as an antidote to HIV infection, Zuma will be under considerable pressure to ensure an approach to the disease thoroughly approved by current medical science.

Thirdly, since Zuma has shown skills as a reconciler in KwaZulu-Natal and Burundi, and also seems more secure in his own cultural identity than the remote and Westernised Mbeki, the hope is that the race tactic will feature less in the discourse of both government and ruling party.

My personal hope is that, like the parent who has missed out on an education and pushes the children to learn, and who makes great sacrifices for their education, Zuma will tackle what is still the biggest obstacle to the development of this country – the dysfunctional public education system. If he could do that he could be remembered as a great man.

The Zulus are warriors. Zuma has fought and won his political battle. The question is whether he can now follow through and prevail over the remaining social evils which still beset us.

Chris Chatteris SJ is the Media Officer for the Jesuit Institute, South Africa.