Damien of Molokai, a Belgian saint who spent half his life in Hawaii and who is known for his ministry to the lepers who lived in isolation in the settlement of Kalaupapa, was canonised on 11 October 2009. Teresa White FCJ considers the model of holiness that we find in Damien’s life, particularly as it is dramatised in Aldyth Morris’ play, Damien.

Damien of Molokai was canonised in the autumn of 2009, and during a visit to Brussels around that time, I went to see a performance of Damien, a one-act play by the American writer, Aldyth Morris. The play takes the form of an imagined soliloquy spoken by Damien as he travels by boat from the Hawaiian island of Molokai to Leuven, Belgium. Such a voyage did indeed take place, in 1936, but it was the saint’s dead body which was brought back to his homeland in that year. He had died almost half a century before, in 1889.

As Damien looks back on his life from beyond the grave, the people who played a part in the drama of his life are given due attention, but their significance is filtered through certain vivid memories which he chooses to share with the audience. He does this with unaffected honesty. In many ways, the man we meet in this play does not fit the categories of traditional Catholic hagiography – indeed he finds it somewhat ironic that he should considered to be of interest or importance to church authorities after his death, given that he so often clashed with them in his lifetime. This Damien is ‘real’ and human, with faults and failings as well as astonishing grit and determination. He is passionate and compassionate, hot-headed and impulsive. Above all, he has a wry and self-deprecating sense of humour that is both engaging and endearing.

In language that is sometimes poetic, Damien’s musings are shaped by a series of incidents, by turn comical or painful or disturbing. Strict chronology has no place in this play, and one vivid memory leads to another. The enduring theme is the rejected people to whom this man had unconditionally given all that he was, and the inhospitable island that had been his chosen home for sixteen years. He remembers both people and island with warmth and affection.

Jozef de Veuster was born in Flanders on 3 January 1840. His father was a down-to-earth man, and he wanted his younger son to work with him on the family farm. But Jozef had other ideas. His older brother, Wenceslas, was a member of the Missionary Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary (SSCC), who had a community in Leuven, and Jozef longed to be a priest like him. In his habitually direct manner, he told his father this, but the news was not well received.

Jozef turned twenty in 1860, and not long after his birthday, he was taken by his father to Leuven, where, to his amazement, the whole community seemed to be expecting him. At the end of the day, his father returned home, leaving his son behind, and Jozef realised that he was now free to begin his training as a priest and religious. He had not even said goodbye to his mother, and he regretted this, but he knew in his heart that his deepest desire was being fulfilled. He entered the novitiate, taking the new name of Damien.

Four years later, Wenceslas was named to go to Honolulu, but he fell ill and was unable to travel. When Damien begged his superiors to be allowed to go in his brother’s place, permission was reluctantly given, and in 1864 he left Belgium for his new mission. This time he did say goodbye to his mother, promising her that he would return home after twelve years. Ordained priest in Honolulu Cathedral a few months after his arrival, he went first to Puna on the Big Island, and was then sent to North Kohala, where he stayed for nine years. It was while he was in Kohala that he learned about the settlement on the island of Molokai, where the lepers had been exiled by the Hawaiian Government. He visited the island frequently, and eventually he was given an ultimatum by his bishop: either to stop going there once and for all, or to go and stay for ever. He had no hesitation: he would go to live with the lepers, he would be their priest. After much procrastination and questioning by his superiors, he was finally given permission to do this.

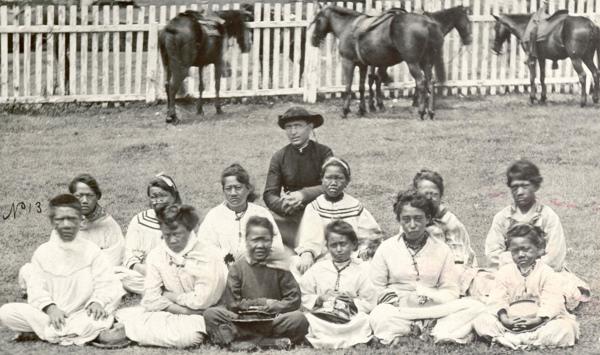

Damien found the secluded settlement of Kalaupapa on the island of Molokai teeming with lepers, more than a thousand of them, living in the most appalling conditions. At first, repulsed by their damaged and misshapen limbs and especially by their facial disfigurements, he said he had to force himself even to look at them. But he learned to love them, deeply and genuinely. His concern for them led him to expose the shameful state of affairs on the island, and he had no hesitation in begging for help in his clean-up operations. He championed his people with characteristic energy doing everything he could to improve their lives. Not surprisingly, he found the usual mix of good and bad among them. They were lepers, he said, but they were not all angels. Sometimes he was shocked and sickened by what he called their ‘sinful’ ways. His anger flared out when he found that a number of the men had been abusing the children. He said he could have killed these men with his bare hands.

On the voyage home, the older, wiser Damien looks back on his youthful self, and acknowledges his naivety and enthusiasm when he joined his missionary congregation at the age of 20 and, a few months later, made vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. At that tender age, what, he asks himself, did he know of poverty, the grinding, degrading poverty that he, as a shepherd, later witnessed in the lives of his flock? Chastity, giving his heart to God alone – that he did with all the idealism and eagerness of youth. Reflecting on this vow, he recalls a Hawaiian wedding he had once attended. After all the festivities, the guests were given sleeping accommodation in a huge barn, with men and women bedding down together. When a beautiful young woman lay down beside him, he felt unsettled by her proximity and was unable to sleep. He eventually got up and walked out into the moonlight. A slight sound made him look back, and there, framed in the doorway, was this woman, totally naked, beckoning to him. He was transfixed, and for a long moment could not tear his eyes from her. God’s strength upheld him, he said. He did not return to the barn but instead roamed the island for the rest of the night. With his usual honesty, he admits that the vision of that naked female body appeared between the pages of his breviary for many weeks and months afterwards. As for the third vow, obedience, how could he have known, at the age of 20, what the cost of it would be for his headstrong, independent spirit? So many battles with church authorities, so many arguments and bitter disagreements with his superiors, as he fought for the lepers, fought for humane conditions and a modicum of comfort for these people who had lost everything and lived in squalor.

He acknowledges that the loneliness of life on Molokai, especially after he contracted the disease himself and could not leave the island, was at times almost unbearable. He was beset by homesickness and longed to see his family, heartbrokenly remembering his promise to his mother all those years ago. Even the sacrament of Confession, which had always been balm to his scrupulous soul, was surrounded with difficulties. He remembers the time when his provincial came to visit him but was not allowed by the captain of the boat to set foot on the island. The boat was moored offshore, and the provincial stood on deck while Damien shouted out his confession – his pride, his anger, his disobedience – for all to hear. There was no healing touch: the words and gestures of absolution were carried to him from a distance, increasing his sense of isolation and abandonment.

An interesting touch in the play, in keeping with the writer’s portrayal of Damien as a ‘modern’ character, is his ecumenical outreach – though he himself would not have used that term. He sees his vocation to work among the lepers on Molokai as a ministry to all of them, whether Catholic or not. He asks the question, ‘What do you say to a dying leper, begging for the comforting sign of God’s forgiveness? Do you ask if he or she is a Catholic, and withhold the Sacrament from those who are not?’ To him, the answer is clear and he follows his own conscience; but the church authorities of the time did not approve of this all-embracing brand of priestly ministry.

The climax comes when Damien describes how, in his mid-forties, he discovered that he too had contracted leprosy. Bathing his sore feet one night, he poured steaming hot water into a bowl, put one foot in, then removed and dried it. As soon as he put the other foot into the bowl, he squealed, reaching for a jug of cold water to reduce the heat. Then he looked at his first foot – it was covered in blisters, and he had felt nothing. He knew this was the beginning of the end for him. The next morning, at Mass, he linked himself with the whole congregation: ‘We lepers...’ he said. They had often heard him say this, but the way he spoke that day made it clear to them all that this time it was literally true. He died four years later, at the age of 49.

On that imaginary voyage home to Belgium, Damien’s reflections lead him to a keen awareness of a major conflict within him. His campaigns for the human rights of the lepers had drawn universal attention and they became increasingly successful. He had been regarded as an international hero, and he knew he had responded to this acclaim, accepted it, relished it. He had not sought popularity but neither had he dismissed it. Admitting that he had not always inwardly and openly attributed all his achievements to God, he confronts the doubts that pierce him to the core. Why had he asked to go and live on Molokai? Why had he done all that campaigning? Was it really for the lepers’ sake? Or was it for himself, to boost his own prestige? Had the whole endeavour been little more than an ego-trip? Had he quite simply been ruled by pride? In the play, peace only returns to him when he reaches his journey’s end and is laid to rest in Belgium.

Aldyth Morris’s portrayal of Damien of Molokai includes the standard biographical details concerning his background and his ministry among the Hawaiian lepers. Yet her script has a unique freshness and vigour: it comes alive because the words are spoken by Damien himself. A man of deep faith is reviewing his life, sharing some of the insights and understanding that he has gained with the passing of the years. This man confides in the audience, creates an atmosphere of touching intimacy through his candour and integrity. The portrait Morris paints of this unlikely candidate for canonisation is colourful and vibrant. Her short play extends the boundaries of sanctity. Yes, sanctity means living a God-centred life, but to be holy also means being involved in the struggles of life, coping with suffering and difficult relationships, and facing times of helplessness and failure. In these terms, she seems to say, Damien of Molokai is a true saint.

Sister Teresa White belongs to the Faithful Companions of Jesus. A former teacher, she spent many years in the ministry of spirituality at Katherine House, a retreat and conference centre run by her congregation in Salford.