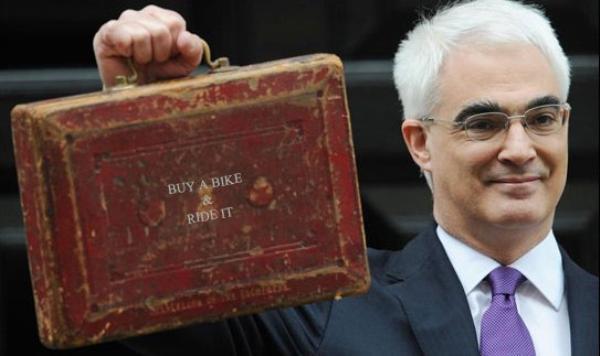

Introducing his budget last week, Chancellor Alistair Darling said, “our greatest obligation to future generations must be to tackle climate change” and declared, “we need to do more and we need to do it now.” CAFOD’s George Gelber analyses how closely the measures the Chancellor has put in place correspond to these uncompromising resolutions.

Last Wednesday, CAFOD called for bolder measures on climate change from Alistair Darling, Chancellor of the Exchequer in what was heralded as a ‘green budget’. It was a week replete with news emphasising the urgency of addressing climate change and underlining the timidity of the chancellor’s measures. On Monday, Javier Solana, the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs underlined the security threats posed by climate change; on Friday, EU leaders agreed to finalise by the end of this year ambitious plans to cut energy use and fight climate change; also on Friday, Tony Blair, adding another role to his post-prime ministerial portfolio, set himself a mission of securing a post-Kyoto treaty that will deliver a 50 per cent cut in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050; and on Sunday we were told that glaciers worldwide are melting at a faster rate than at any time in the last 5,000 years.

Climate change deniers are a dying breed. Few now are prepared to challenge the overwhelming scientific consensus concerning human activity and its impacts upon the climate. The opposing camps on climate change are those who question the wisdom of spending vast sums of money now on the difficult and uncertain project of slowing and ultimately halting climate change and those who are calling for far-reaching measures now to achieve the UK target of reducing our greenhouse gas emissions by at least 60 per cent by 2050 in comparison with 1990. Alistair Darling himself said in his budget speech that the government were considering increasing the target for reducing CO2 emissions to 80 per cent, the level that experts now believe is the minimum necessary to prevent global temperatures increasing by more than 2º Celsius, the limit beyond which there could be runaway, unpredictable climate change.

The message of Sir Nick Stern’s review on the economics of climate change[1], published by the Treasury in 2006, was that an ounce of prevention will be better than a pound of cure. Stern estimated that a “Business As Usual” approach to economic growth, that is doing nothing to mitigate emissions, would eventually cause welfare losses of between 5 and 20 per cent in global income, whereas the annual cost of containing greenhouse gas concentration in the atmosphere within the (too high) 500-550 parts per million limit would be in the region of 1 per cent of global income. The sums involved are perhaps comparable to what has been spent on the nuclear deterrence since the beginning of the cold war. The argument for spending to contain climate change is even more persuasive, because climate change is a current and accelerating reality.[2] In other words, there is a precedent for spending very large amounts of money actively to prevent disaster.

2050, however, the target date for reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 80 per cent is a long way away. And as with all far-off targets, whether it’s a personal pension plan or, say, the Millennium Development Goals with their nearer target date of 2015, it’s too easy to postpone the first vital steps. The consequence, inevitably, is that the first steps will become more painful because there is lost ground to be made up or, more likely, that the target will not be achieved.

Alistair Darling was able last Wednesday to announce hefty increases in duties and taxes on alcohol and tobacco, because he was confident that public concern about alcohol-fuelled excess and tobacco-related illness would ensure that any protest was manageable. Yet, given the opportunity of demonstrating that the UK is serious about climate change, Darling opted for the approach to chastity of St Augustine, who prayed, “Lord make me chaste … but not yet.” The 2p per litre increase in fuel duty, itself not enough to change behaviour, was postponed to October and the £950 showroom tax on gas-guzzling vehicles will take effect in 2010. There were several announcements of more far-reaching measures, such as making new non-domestic buildings zero-carbon by 2019, but these were all comfortably in the future and there was little sign of early or immediate changes in the incentives – sticks and carrots – needed to wean us away from our energy-hungry way of life. It was left to Ken Livingstone to provoke howls of outrage by introducing a £25 a day congestion charge for gas-guzzling vehicles.

Why was the chancellor so timid? Is it because he and Gordon Brown believe that they will be punished at the ballot box? They might argue that, as a nation, we aspire or are already addicted to a way of life which puts a car outside our front doors, offers affordable travel to far away places and brings the products of the world to our high streets. Interfering with this view of the good life in order to attenuate climate change which has yet to make its full impact on our world is politically risky. In recent climate negotiations both George Bush and the Chinese leadership have opted for growth now rather than sustainability in the future. It is future generations who will curse us for our lack of vision and nerve or thank us for our foresight and determination – but future generations have no vote in any proximate elections.

At the same time the government’s fondness for complex, market-based solutions makes it unwilling to approve the subsidies that other European nations are giving to their renewable energy industries. The result is that the UK is falling behind other countries: in Germany, for instance, the share of electricity from renewable energy increased from 6.3 per cent in 2000 to 12 per cent in 2006 while in the UK only 2 per cent of our electricity comes from renewable sources. The government is committed to sourcing 15% of all energy from renewable sources by 2015, a target likely to be agreed with the EU. But the gap between our present reality and the language and aspirations of government is alarmingly large – and the government is unwilling to deploy the instruments that have enabled other countries to make such good progress.

The industrialised countries are responsible for climate change. It is our profligate use of fossil fuels over more than two centuries which has brought us both our present standard of living and climate change. This constitutes our ecological debt and is the reason why developing countries understandably are demanding that we, the rich industrialised countries, should shoulder the responsibility of making the reductions in greenhouse gas emissions that are needed to stabilise the proportion of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Developing countries fear, however, that with our dominance of international institutions, we will seek to pull up the ladder of economic growth and development just as it appears to be within their grasp. But not all developing countries are the same – China in particular is mimicking our history with its own headlong power-hungry industrialisation and is now set to surpass the United States in its emissions of greenhouse gases. India, also in the throes of rapid economic growth, is not far behind. At the same time, China and India, both countries which are vulnerable to climate change and are already experiencing its impacts, are doing their own excellent work on renewables and energy efficiency, and cannot, and should not, be cast in the role of climate change villains. Chinese officials angrily point out that there are three times as many people in China as in the US and that their emissions per head are less than a third of those of the United States. The Chinese foreign minister commented, “It's like there is one person who eats three slices of bread for breakfast, and there are three people, each of whom eats only one slice. Who should be on a diet?”[3]

CAFOD would also have liked the budget to recognise that many developing countries are already perforce having to adapt to the climate change that is already happening. Their weather is becoming more variable; rainfall, on which many poor people depend for survival, is becoming irregular; sea levels are rising; and extreme climate events are more frequent. And all this requires investment now, to secure livelihoods and make people safe. We would have liked Alistair Darling to announce that increasing taxes here would enable him to provide additional development assistance for such purposes, but it was not to be.

Rich nations are now being scrutinised by developing countries as never before. We have made extravagant promises on development assistance, and many of the biggest donors – but not the UK to its credit – are not on track to fulfil their commitments. And now, the UK and EU member states are on the verge of making another huge, long-term set of promises, committing us to consistent action over many years. It is good and important for the UK to have a climate change law but it will be empty of meaning and effect if it is not backed up by resources and action. The gap between the UK’s rhetoric and its reality threatens to undermine its credibility and legitimacy on the international scene, particularly its efforts to encourage the US and the emerging economic superpowers of China, India and Brazil to sign up to an international agreement. The UK, which has been at the forefront of advocacy on climate change, will need to show that it has the determination to will the means as well as the ends.

George Gelber is Head of Public Policy at CAFOD.

[1] See HM Treasury:

[2] a) It is estimated that between 1940 and 1996 the total expenditure on nuclear weapons of the US alone was $5.821 billion in 1996 dollars. If all nuclear powers together spent, say, three times this figure ($17.463 billion) over the same period, then this is on average equivalent to approximately 1% of annual world income. See Stephen I. Schwartz – Atomic Audit: the costs and consequences of US nuclear weapons since 1940; Brookings Institution Press; Washington D.C. 1998

b) Total world income in 1997 was $29,927.7 billion in 1997 dollars – World Bank, World Development Report 1998/99

[3] AFP – 12 March 2007 China tells developed world to go on climate change 'diet'