In the first instalment of a three-part series, adapted from his lecture at the 2008 Living Theology summer school at Ushaw College, Paul D. Murray introduces the scriptural and theological contexts in which Catholics should explore and reflect on the notion and practice of dialogue.

Introduction

When I mentioned to a close friend, who is sadly no longer a member of the Church, that I was to present a lecture on ‘Dialogue and the Church’ he promptly retorted that it would be a difficult task given that Catholicism is more given to monologue than dialogue. After a pause, he added that it should at least have the advantage of evoking an uncharacteristically short contribution from me. Well, you may be reassured and dismayed in equal measure to hear that he was wrong on both accounts. As I told him, whilst Catholicism may indeed still have a way to travel into the full potential and implications of dialogue, both in relation to others and in relation to its own internal life, it is equally the case that Catholicism has a long-term and intrinsic relationship with the way of dialogue. And as I also told him in relation to his second point, he should never underestimate an academic’s ability to go on at length about anything.

My Context – Receptive Ecumenism and Ecumenical Dialogue

My own closest engagements in theological dialogue have been on two somewhat different fronts. In the past I have been engaged with the respective interfaces between theology and modern philosophy, and theology and aspects of scientific understanding. [1] More recently and with clearer practical relevance, I’ve been fairly involved in intra-Christian ecumenical encounter and learning. Here I’ve been particularly involved in developing and testing a proposed new strategy going by the name of Receptive Ecumenism which seeks to respond to the particular ecumenical context in which we now find ourselves. [2]

Four key aspects of this context are: 1) the waning and disappointing of the ecumenical optimism – over-optimism? – that marked the late 1960s and 1970s, and into the ‘80s; 2) the recognition that whilst the resource-intensive ecumenical dialogues have indeed led to markedly increased levels of mutual understanding and the resolving of some historic knots of disagreement, they have not delivered structural unity; to the contrary, 3) they have actually led, in some respects, to the respective parties becoming clearer both about the areas of real, continuing difference between them and that these cannot be resolved by discussion alone but require some degree of real movement, or conversion, by at least one party; 4) consciousness also that alongside these existing long-term differences are various more recent issues, such as female ordination and the explicit acceptance of practising homosexuals, that have, for the short-medium term at least, intensified rather than reduced what are regarded as communion-dividing differences.

Within this context, the remarkably simple principle at the heart of Receptive Ecumenism is that rather than asking the question, as much ecumenical work effectively does, “What do our various others first need to learn from us?” priority should instead be given to the self-critical question “What do we need to learn and what can we learn – or receive – with integrity from our others?” Or again, “How might the specific difficulties we experience in our own thought and practice be eased by learning from our ecumenical others?” The conviction is that if all were acting on this principle, even relatively independently of each other, then change would happen on many fronts, albeit somewhat unpredictably. As such, Receptive Ecumenism values and presupposes the work of the formal ecumenical dialogues, whilst viewing them as incapable alone of delivering the self-critical openness to practical conversion, growth and development upon which all real progress depends. The dialogues excel in mediating and translating between differing, apparently conflicting, doctrinal languages and even showing them, on occasion at least, to be compatible. In the very act of so doing, however, the danger is that they will leave these differing yet potentially compatible languages in themselves relatively unchanged.

Despite its simplicity, then, there is also something counter-intuitive about Receptive Ecumenism in as much as it seeks to contribute to Christian unity by not aiming at it directly. In the first instance, it seeks not agreement between separated traditions but transformative, receptive learning within such traditions. Indeed, in the short-medium term it seeks not to collapse differences but to intensify and complexify them. It seeks, we might say, long-term conversion to a new place rather than short-term convergence upon any existing position.

So then, whilst valuing dialogue highly and, indeed, desiring to see rather more of it at all levels and on many fronts, I do not view it in itself as some kind of panacea, or cure-all; particularly so if conceived in terms of the task of bringing what are effectively regarded as differing complete, static systems into conversation with each other. In this view, dialogue must either be complemented by, or already contain within itself as an aspect of its operation, the kind of concern for dynamic receptivity with integrity that Receptive Ecumenism represents in the intra-Christian ecumenical context.

Scriptural Reflections on Christ, Creation and Catholicity

Reflect for a moment on these three scripture passages:

Genesis 1: 1-3

1In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth, 2the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters. 3Then God said, ‘Let there be light’; and there was light.

Colossians 1:15-17

15He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation; 16for in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers—all things have been created through him and for him. 17He himself is before all things, and in him all things hold together.

John 1:1-5

1In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. 2He was in the beginning with God. 3All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being. What has come into being 4in him was life, and the life was the light of all people. 5The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.

(NRSV)

These passages are, I suggest, fundamental to a Catholic vision of the world. Sure, there are other things not said here that we would also want to say – concerning, for example, the sin-distorted character of created reality and its need for redemption. So, whilst not entire and sufficient of themselves, what we find here is, nevertheless, fundamental to that vision. When read within a Christian interpretative framework, what we are presented with here – as, more generally, from the first word to the last word of the scriptural narrative – is a vision of all that exists as having its origin, existence and promised consummation in God in Christ and the Spirit, in whom, as St. Paul is recorded as saying, all things live, move and have their being. In this perspective, all of reality whilst sin-dimmed and frustrated is, nevertheless, of intrinsic theological significance and capable of showing forth something, even if only partially and in confused form, of the reality of God.

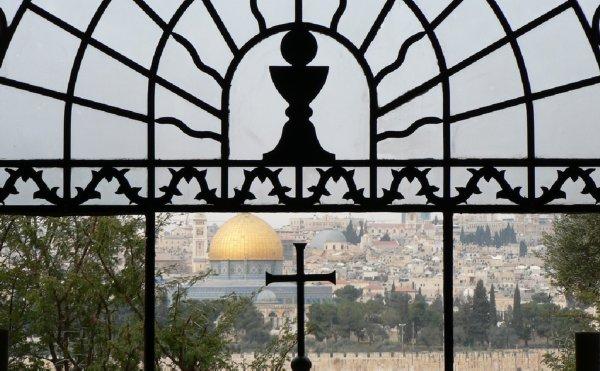

Theologically speaking, the word ‘dialogue’ is itself suggestive of this vision. With its origins in the classical Greek word for the art of reasoned disputation, it came to refer more generally to communication between people aimed at identifying meaning. In turn, this has been put to work theologically to speak, by analogy, of revelation as God’s communication of meaning to creation, and this not simply through created words but in and through the Word that is God’s eternal means of self-expression. Indeed, in the light of these passages, more fundamental even than speaking of revelation as communication in and through the Word, we need to speak of creation itself as an event in and through the Word in the power of the Spirit. And behind that, in turn, of course is the most fundamental reality of all, the Trinitarian life of God which simply is a, indeed the, fully actualised event of dialogue; of being through the Word in the Spirit. More in that latter regard later; for now, we can simply note that these passages can thus be seen to open for us a vision of the entirety of reality as having intrinsic Christological significance. The cosmic Christ is not simply a post-resurrection, post-ascension phenomenon but the deep principle, the form and means of creation from all eternity. These passages, we might say, take us into the mystical heart of Catholicism and recall for us the deep logic of our sacramental sensitivity.

In fact, the very word ‘Catholic’ already points us to this vision. If one asks Roman Catholics what the word ‘Catholic’ means, one might typically be told that it means something to do with being in communion with the Bishop of Rome. Even more likely is that one will be told that it means ‘universal’. There’s something unquestionably right about that. The notion that the Catholic Church is universal, everywhere – the great Church universal, co-extensive with the inhabited world and not some localised sect – stems from the time when that self-consciousness of the church broke through. We find this explicitly in Cyprian’s writings, for example, in the 3rd century, and we might see it as being in implicit in St. Paul’s impassioned concern to take the Gospel, following the great commission, to the ends of the earth. But behind this notion of spatio-temporal, or geographic, universality that goes so deep in the Catholic psyche, ‘Catholic’ first bespeaks a prior, more explicitly Christological universality.

From the Greek adverbial phrase kath’holou, literally meaning ‘according to the whole’, or ‘in accordance with the whole’, it seems that the first usage of ‘Catholic’ in relation to the church was by Ignatius of Antioch some time towards the end of the first century in order to distinguish the Catholic Church that understood itself to maintain the whole truth of Christ from heretical sects who were regarded as settling for partial, distorted understandings of Christ. The deep connection between this early and explicitly Christological usage of Catholic and the later extension of this in the direction of spatio-temporal universality is to be found in the kind of perspectives that we have been exploring in relation to our scriptural passages. The point is that as variously written into the deep fabric of creation, the whole truth of God in Christ and the Spirit requires an ever-renewed attentiveness to what may be disclosed of Christ and the ways of the Spirit in the diverse particularity of created reality.

We earlier touched on what we might refer to as the Petrine dimension of Catholicity – the centripetal instinct for holding things together, for thinking according to the whole of the Church through communion with the Bishop of Rome. What we are now saying regarding the task of thinking in accordance with the whole truth of God in Christ and the Spirit as having resonance with the entirety of reality points us to another dimension of Catholicity that complements this. In this year of St. Paul, we might refer to this complementary, centrifugal instinct as the Pauline dimension of Catholicity. Where Peter and the Petrine instinct represents the concern, as it did also in the Apostolic period, to hold what we have together, Paul and the Pauline represents the instinct to explore the new frontiers of understanding and practice into which the Spirit appears to be leading us.

The necessary complementarity between these two instincts came home to me very vividly during my first visit to Rome in September 2005 in the context of a planning visit for the first Receptive Ecumenism project. My wife, Andrea, and I were staying at the Beda College which is situated a short way out from the centre, opposite the Basilica of San Paulo Fuori le Mura, St Paul’s Outside the Walls. Each day, either for meetings with staff of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, or for reasons of pilgrimage and sightseeing, we had cause to travel in from St Paul’s to St. Peter’s and back again. After a number of days shaped by this rhythm, it struck me that that really is what it means to be Catholic: to live between the embracing arms of Bernini’s colonnades, gathering all into communion, and the outward-facing stance of St. Paul’s Outside the Walls. It is for good reason that Pope John announced the Second Vatican Council whilst visiting St. Paul’s and it is for good reason also the start and end of the Octave of Prayer for Christian Unity takes place here.

So, Catholicism exists between a centripetal gathering and holding, and a centrifugal dispersal, challenge and renewal: between these apparently contradictory but complementary dimensions of the Spirit’s activity. Sure, there is an inevitable tension between these dimensions but it should be a creative tension that we eradicate to our mutual impoverishment. To diminish either one is to diminish our Catholicity. And in this regard it is, perhaps, to state the obvious to say that our tendency as Roman Catholics is to over-achieve on the Petrine to the expense of the Pauline. Indeed, it may be that we as Roman Catholics need to re-receive the authentically Pauline dimension to our Catholicity from our Protestant brothers and sisters and the practices and structures that operate in their churches.

Paul D Murray is Director of the Centre for Catholic Studies and Senior Lecturer in Systematic Theology in the Department of Theology & Religion at the University of Durham. He is the Editor of the forthcoming volume, Receptive Ecumenism and the Call to Catholic Learning: Exploring a Way for Contemporary Ecumenism (Oxford University Press).

This article was adapted from the keynote lecture given by Dr Paul D. Murray the 2008 Living Theology summer school at Ushaw College, Durham.

![]() Read Part Two of this series

Read Part Two of this series

[1] See, for example, Murray, Reason, Truth and Theology in Pragmatist Perspective, (Leuven: Peeters, 2004); ‘Truth and Reason in Science and Theology: Points of Tension, Correlation and Compatibility’, in God, Humanity and the Cosmos: A Textbook in Science and Religion, C. Southgate (ed.), (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1999), pp. 49-92; ‘Epistemology’, in The International Encyclopedia of Science and Religion, Vol. 1, J. Wentzel van Huyssteen (ed.), (New York: Macmillan Reference, 2002), pp. 266-8.

[2] See Murray (ed.), Receptive Ecumenism and the Call to Catholic Learning: Exploring a Way for Contemporary Ecumenism, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008); also ‘Receptive Ecumenism and Catholic Learning: Establishing the Agenda’, International Journal for the Study of the Christian Church, 7 (2007), 279-301.

![]() Living Theology

Living Theology![]() Centre for Catholic Studies

Centre for Catholic Studies![]() 'Receptive Ecumenism and the Call to Catholic Learning' edited by Paul Murray

'Receptive Ecumenism and the Call to Catholic Learning' edited by Paul Murray