Zimbabwean Jesuit David Harold-Barry looks at the concept of power expressed in the letters of St Paul, as part of Thinking Faith’s series for the Pauline Year. How does Paul’s idea of power differ to the manifestations of political power we see today?

People who observe Zimbabwe from afar often explode, ‘Why is the situation going on so long? Why don’t you do something? Why don’t you get rid of that man who is blocking everything?’ Those of us who live here do not ask these questions. We have tried every constitutional way of changing our government, which long ago ran its time, but the man at the top is determined to remain in power. We are not interested in violence; we had years of it in the struggle for independence and they were deeply traumatic. And besides, bad as our situation is, we have no wish to find ourselves alongside Kivu and Goma, suffering the same misery as that caused by the Rwandan genocide.

But there is perhaps a deeper reason which we do not often put into words. Our president uses force to stay in power but to use force to remove him would be inviting for ourselves decades of instability. We prefer to wait. Eventually circumstances will abound that will make change inevitable. Something like that happened in South Africa. I am one of the many who believed in the 1970s that the war in Rhodesia would be a picnic compared to the war that would eventually break out in South Africa. We were wrong. There was no war. What happened was an accumulation of circumstances that made it impossible for the government of the day to carry on.

The makers of the European Union took decades to piece together a community of 26 nations and they have been building on rock. It will last. For the first time in millennia we can say with certainty there will never again be a war between European nations. That is an amazing achievement of the human spirit.

And it is the only way to build a nation. What we are living through now in Zimbabwe is painful but it is not time lost. People in their thirties and forties, educated reflective people, have observed what has been happening this past ten years and they are deeply embarrassed by the continued presence of ‘the old man’. But they want to see him go peacefully. Meanwhile they are consciously planning the sort of society they want. They now know – by a sort of via negativa - what good governance means and what effective management of the economy means. We will never again tolerate someone bulldozing his way through the institutions of the state.

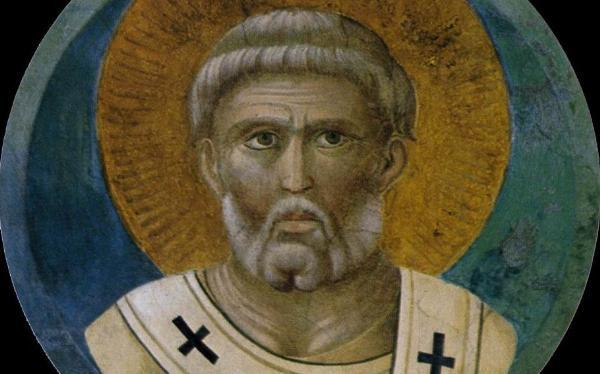

In this year of St Paul we have a sure theological base for this way of seeing things. Paul often talks of power but in a way quite different from our leader.

May the God of hope fill you with all joy and peace in your faith, so that in the power of the Holy Spirit you may be rich in hope. (Rom 15:13).

Glory be to him whose power, working in us, can do infinitely more than we can ask or imagine. (Eph 3: 20)

There is exterior power, which is the imposition of something by brute force, that has no relationship to the reality on the ground. There is also interior power, which is what Paul refers to. It is doing something, often painfully and slowly, that relates, as it were organically, to some need on the ground and which ultimately people accept because it has an interior logic. This is the power Paul writes of. And he is quite blunt about it: for Paul, power means the cross.

The message of the cross is folly to those who are on the way to ruin but for us who are on the road to salvation it is the power of God’ (I Cor 1:18).

For Paul, power, paradoxically, means submission – submission to the reality there before us. Nicholas King SJ calls the Letter to the Romans ‘a love story’ in the sense that it describes God’s love for humanity. Jesus showed his love by accepting the cross. This ‘folly’ shows the true meaning of power. Paul uses all sorts of images to describe power; who else would use the word ‘weakness’ to describe power? “For it is when I am weak that I am strong.” (2 Cor 12:10)

Another way – perhaps the way that sums up all others – is his use of the phrase, ‘the obedience of faith’ at the beginning and the end of his letter to the Romans (1:5 and 16:26). For Jesus there was a necessity to undergo the cross. Since he listened to the Father he understood that there was no other way. Once the Trinity decided that the second person would become man (to use St Ignatius’ presentation of the Incarnation in the Spiritual Exercises) there was an internal logic about the cross. There was no other way of achieving his aim. If he was to ‘save’ the human race and ‘all creation’ he had to enter the struggle which human beings were enduring. Irenaeus did not speak much about the death and resurrection of Jesus. What was important was the incarnation. Once you have the incarnation you have everything. Because he is who he is the very fact of his becoming one of us means that he will show us the way by what he does as well as by what he says.

Jesus tried, with some initial success, to convince people about the message of the gospel. But as time went on, together with the ‘admiration of the crowds’ (Luke 5:26) there was the growing hostility of the ruling classes. He could have asked for ‘twelve legions of angels’ (Matt 26:53) but that would be an expression of Mugabean power. No, he allowed himself to be handed over to them. He confronted them in the only way that had an interior connection with the opposition that the ruling classes were expressing. He entered deeply into the human experience of sin with its refusal to believe, its deceit, selfishness, greed and cruelty. ‘The Son of God enters into the depths of this world’ (Leo the Great). He laid the axe to the root (Luke 3:9). He submitted in obedience to the inner logic of the human situation.

His submission was in his entering fully into the experience of human beings, entering into their pain – a pain which up to that time had no meaning, as it still has no meaning for millions of our contemporaries. He actually died as we die and entered into the underworld – the home of sin and death and alienation, symbolised by his being buried in the earth for three days. But because he was who he was death could not hold him. Since he was the source of life he burst forth from the tomb and in so doing removed the sting of death and with it all the effects of sin. His rising was the definitive conquest of these negative forces. In this way he showed the power of which Paul speaks. He ‘accepted death’ (Phil 2:8) ‘learning obedience, Son though he was, through his sufferings’ (Heb 5:8). This obedience of Jesus is the only way to live.

That is why Paul sees his mission as calling ‘the nations’ (Rom 1:5) to this same obedience. Power comes from an acceptance, a submission, an obedience, to human reality of which the cross is the most powerful symbol. The Carthusian motto is stat crux dum volvitur orbis – the cross is the one fixed point in a world that is forever in motion.

In the world of politics, the word power is in constant use. You are either ‘in power’ in which case you can do anything, or you are out of it in which case you are helpless. The past nine years of Zimbabwean history illustrates this adequately. However, for Paul, power does not mean ‘making one’s authority felt’. A true understanding of power means that it can never be an arbitrary manipulative exercise of force which takes little or no account of the reality on the ground. True power does not impose itself but receives or perhaps absorbs reality.

May He, through his Spirit, enable you to grow firm in power with regard to your inner self, so that Christ may live in your hearts through faith, and then planted in love and built on love, with all God’s holy people you will have the strength to grasp the breadth and length, the height and depth, so that knowing the love of Christ, which is beyond knowledge, you may be filled with the utter fullness of God. Glory be to him whose power, working in us, can do infinitely more than we can ask or imagine. (Ephesians 3:16ff)

David Harold-Barry SJ is the Director of Silveira House Development Education Centre in Chishawasha, Zimbabwe.

Read more of Thinking Faith’s series on Saint Paul:

![]() Who Was Saint Paul? – Peter Edmonds SJ

Who Was Saint Paul? – Peter Edmonds SJ

![]() The Long Road to Damascus – Bishop John Arnold

The Long Road to Damascus – Bishop John Arnold

![]() Paul the Pastor – Jerome Murphy-O’Connor OP

Paul the Pastor – Jerome Murphy-O’Connor OP

![]() The Vision of Saint Paul – Nick King SJ

The Vision of Saint Paul – Nick King SJ

![]() Getting to know Saint Paul today – David Neuhaus SJ

Getting to know Saint Paul today – David Neuhaus SJ

![]() Paul, Trinity and Community – Michael Mullins

Paul, Trinity and Community – Michael Mullins

![]() St Paul and Ecumenism – Bishop John Arnold

St Paul and Ecumenism – Bishop John Arnold

![]() The Letter of Paul to the Philippians – Peter Edmonds SJ

The Letter of Paul to the Philippians – Peter Edmonds SJ

![]() Thinking about Christ?s Resurrection in the Year of St Paul – Gerald O?Collins SJ

Thinking about Christ?s Resurrection in the Year of St Paul – Gerald O?Collins SJ

![]() The Letter to the Colossians: Jesus and the Universe – Brian Purfield

The Letter to the Colossians: Jesus and the Universe – Brian Purfield