This Sunday 21st March marks World Poetry Day, but how many of us dismiss contemporary verse as being incomprehensible or too high-brow? We should think twice before we turn our backs on it, argues Nathan Koblintz, especially if our reason for doing so is that such poetry cannot speak about God. How can a Christian find value in even seemingly atheistic poetry?

You’ll be in the minority if you know that Sunday 21st March is World Poetry Day. We can expect a brief discussion in the press about the relevance of poetry to contemporary British society. Is poetry something for the academy alone to appreciate? Is it appropriate for a medium so personal to be used to announce the birthdays of royals or the pomp of state occasion? The debates will flicker briefly, as they did when they were fuelled by accusations of long-distant sexual impropriety in the competition to become the next Professor of Poetry at Oxford. Poetry, an observer might have concluded, was relevant only when it brought out the worst in people.

Why is this? Skimming the surface of reactions to contemporary poetry comes up with complaints that the poetry is difficult to understand, too ‘literary’; to which a reader of Thinking Faith might add: too consistently irreverent, too consistently atheistic, too pretentious to be read with pleasure and benefit by contemporary Christians. As people of faith we are more likely to turn to the past – to a poem like Hopkins’ ‘God’s Grandeur’ – or to assume that any reading of modern poetry that we do must be done with our faith kept in our back pocket in case it clashes too much with what we read. As with any assumption, this turning away from contemporary, non-Christian poetry can become an unthinking habit.

But is there something of value to Christians in poetry that is complex, ‘literary’ and atheistic, or should it just be consigned to the status of a clever game? Can we tempt contemporary poetry out of the doorway in which it slinks (probably up to no good) and get it to explain itself?

*

To begin with here is verse three of Scott Cairns’ ‘Idiot Psalms’ (2009):

A psalm of Isaak, whispered mid the Philistines, beneath the breath.

Master both invisible and notoriously

slow to act, should You incline to fix

Your generous attentions for the moment

to the narrow scene of this our appointed

tedium, should You – once our kindly

secretary has duly noted which of us

is feigning presence, and which excused, which unexcused,

You may be entertained to hear how much we find to say

about so little. Among these other mediocrities,

Your mediocre servant gets a glimpse of how

his slow and meager worship might appear

from where You endlessly attend our dreariness.

Holy One, forgive, forgo and, if You will, fend off

from this my heart the sense that I am drowning here

amid the motions, the discussions, the several

questions endlessly recast, our paper ballots.

Anyone who has sat in a meeting and felt how its ‘mediocrities’ allow people to say so much ‘about so little’ will have likely whispered something similar, if less eloquent, under their breath. What Cairns does is to fuse this humdrum dreariness to God’s endlessly attending presence – He who never sends His apologies for absence nor cries off with a double-booking. The Christianity of the poet gives this poem its life: imagine how the poem would have been written by an atheist poet – perhaps a wry glance at humanity’s ability to organise the passion out of any idea, or the feeling of life passing you by as responsibility clutches you in a bureaucratic grasp. There is no doubt that readers who bring faith to the poem are enriched by the faith of the poet: yes, we might respond, I also have felt my meagreness in the face of God, and here it is expressed before me.

In comparison, this is Simon Armitage on a mountain bike in ‘About Ladybower’ (1992):

Undergrowth nods forward, chimes for a moment

in the spokes,

sticks its neck out and gets strimmed. Bent sticks

rear up like snakes

and are broken. One pot-hole cups the wheel and upends me.

Quickly the home straight,

the landing lights of cat’s-eyes and too soon it is over,

one last long

kinematic free-wheel into the road’s elbow, the whiplash

up and out

along the apron of the lake and a copybook quietness

to glide into.

This too has the charm of recognition about it: anyone who has cycled a bike in the countryside spots her or himself pushing against the slope, or the crazy freewheeling down with gravity where roots and holes interrupt the path. It’s certainly an excellent poem – but what lies behind it? It is simply about the thrill of cycling. In this sense it is a ‘flat’ poem, not in the sense of its energy or attractiveness, but in the sense that it does not invite us into any sense of mystery. The world is made of the materials we see and the emotions we feel; that is all. We are not encouraged to sing out with the Psalmist: ‘For so many marvels I thank you; a wonder am I, and all your works are wonders. You knew me through and through, my being held no secrets from you, when I was being formed in secret, textured in the depths of the earth.’ (Psalm 139, v.14-15) What a Christian gains from it is surely nothing more than entertainment: pleasure rather than joy; recognition rather than exaltation. Cairns’ office meeting is a meeting with God; Armitage rides alone.

But surely faith-filled poetry does not hold a monopoly on depth of vision. After all, one of the complaints levied at contemporary poetry is its esoteric nature, implying that poets have access to the deeper truths of the universe. Here are the first three verses of ‘90 Instant Messages to Tom Moore’ (2006) by Paul Muldoon:

I

Jim-jams and whim-whams

Where the whalers still heave to

For a gammy-gam.

II

Yet another isle

Full of noises. Feral hogs.

The turn of turnstiles.

III

Hamilton. Tweeds? Tux?

Baloney? Abalone?

Flux, Tom. Constant flux.

Discuss that! There are a few facts to throw at it – these are haikus; Tom Moore was an Irish song-writer and poet; the isle full of noises must be a reference to The Tempest; a whim-wham is a fancy ornament. It’s a poem that shouts out its intelligence and complexity: clearly anyone who can understand it is of similar intelligence. Reading and talking about the poem becomes something of a intellectual weight-lifting contest: here’s one critic describing Muldoon: ‘His rhetorical gestures are large, yes, but they are massively self-deprecating, distrustful of every familiar gesture of moral rectitude or emotional sincerity.’ Well, that clears that one up.

The mysteries of the poem feel accessible only to its disciples who have aped the trick of the adulation that reflects as much back on he who praises as he who is praised. Reading Muldoon’s poem feels like struggling for membership to an exclusive club: hardly a spiritually satisfying exercise.

I’ve used these three poems to triangulate some extremes of contemporary poetry. We have the Christian poet’s take on the divinely sustained everyday; what we might call Armitage’s materialist everyday; and Muldoon’s highly ‘intellectual’, complex poetry. At first glance it would appear that of the three only Cairns’ poem is spiritually and intellectually satisfying to a Christian reader in the sense that it reflects back a believer’s view of creation. And yet many ostensibly atheistic poems make reference to life in such transcendent terms that they seem to be crying out for recruitment to a Christian interpretation. Could it be possible even atheistic poets are talking about God? It is to this approach to poetry that I now turn.

*

At the start of one of Don Paterson’s versions of Rainer Maria Rilke’s sonnets, we find this:

God is the place that always heals over, however often we tear it.

(from ‘The Stream’, 2006)

It’s a beautiful phrase, containing much within it: one of those moments when the right words present us with a known truth from a new angle. However, both Rilke and Paterson are atheists. Here is the latter commenting at the end of the book:

Human religion’s demotion of this astonishing situation [that we find ourselves here in the first place] to the status of existential preamble is in some ways its supreme accomplishment. Religion acts as if it holds copyright on the miraculous, and yet is dedicated to eradicating the real wonder from the human experience.

(Orpheus, pp.67-8)

Clearly whatever Paterson means by God being the place that ‘always heals over’, he did not intend it to refer to the always-forgiving deity that a Christian reader might infer. We are therefore left with a few options: do we tell ourselves that Patterson, despite his atheism, has touched upon a heavenly truth? Do we close our eyes to the rest of his beliefs and insist that whatever he meant by the poem, we can take whatever we want from it?

Both approaches seem unsatisfactory: the latter implies a wilful ignorance of the facts of the poem, whilst the former, however true it may be in the way that God works through both believers and non-believers, seems an unsustainable way of reading poetry: although a phrase that starts ‘God is…’ clearly lends itself to a religious interpretation even if written by an atheist poet, what do we do with lines that don’t start so conveniently? Jo Shapcott in bed on top of a mountain:

I’m wondering, as I reach to comfort him,

about love – how it lets in the whole world,

even the cloud sitting on the mountain top,

the awfulness of the stars we can’t see,

the animals, walkers, cars rolling

across the pass, the very dark itself…

(from ‘On Tour: The Alps’, 1992)

Yes, she’s talking about all-encompassing love; about that discovery within herself as she realises her capacity to care for her sulky boyfriend who is now infected with nightmares: but it’s clear from the rest of the poem that she attributes this force to the pagan (the mountain) or the human – full stop. To pretend that she is talking about God, either explicitly or ‘accidentally’, does not really do justice to where she is speaking from.

It’s hard then to read atheist poetry as some kind of secret work of theology. Yoking that responsibility of talking about God onto atheist poems devalues both endeavours. Poetry sometimes talks explicitly about the God in whom we believe – but it always talks about the human. Perhaps it is this approach to poetry that locates its true value.

*

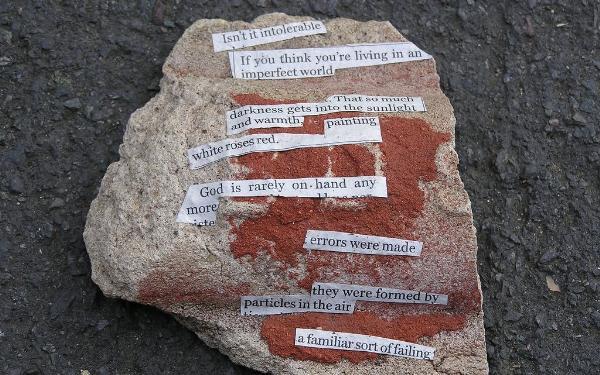

Back to basics then. What is poetry, why the urge to write it? Every poem has of course its own myriad of impulses behind it. But what every poem shares is the desire to record – the words are a kind of blotting paper dipped into the flow of time, to record all aspects of existence: hearing God’s call but feeling dull and tired; the way one relates to a dead Irish songwriter; what it feels like on a mountain bike; a realisation that comes atop a mountain. Everything else that comes on top of this – the ways we are taught at school to talk about poetry, or the critics we might see in a newspaper – are secondary, as is, despite what many critics would have us believe of their mystic-making, the form and the technique that a poet uses. The very fact that something is worth recording, even the smallest of moments, is predicated on the fact that human existence is in some way important.

Thinking about poetry in this way defuses some of the tension between the categorization of poems into silos of Christian or atheistic. Although we may find Christian poems satisfying in the way that they seem to present a truer vision of reality than ones based on materialistic philosophy, every poem is merely a human construction – and not even the most Christian poem is a work of pure theology, or a piece of Church teaching. It is worth remembering that the God of Paradise Lost, often referred to as the epitome of Christian poems, is not necessarily a God that all of us would recognise. Milton was a less a theologian than he was a dramatic poet, and his ‘God’ bears the same relation to the real God as Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar does to the historical man. Christian poems talk about their author’s experience of God and of a God-filled life. The poems of an atheist express something just as human and earth-bound.

Reading any poetry shares with it some of the outward characteristics of praying: it often takes place alone, with focused attention and with (in the words of e.e.cummings) ‘the eyes of your eyes awake and the ears of your ears open’. Like prayer, poetry challenges us to be honest to and about ourselves, in its insistence that nothing should be hidden and that truth should be sought at all times. This search for honesty and truth appears hidden in much of contemporary poetry – why all the games, the word-playing and referencing of obscure texts? – but although the style in which it manifests itself has changed, the impulse has stayed the same.

Reading poetry then can be a way of entering more deeply into what it is to be human. Back to Don Paterson, the avowed atheist:

By all means, turn the page or close the book.

But first, imagine how this world would look

were it not duly filtered, cropped and strained

into that pinhole camera you call a brain

by whose inverted dim imaginings

you presume to question it. So many things

are hidden from you. Luckily. Here’s one.

(from ‘A Talking Book’, 2003)

Imagine how this world looks – a great expansion from the small spots of creation we inhabit. Here with no mention of a God in whom he does not believe, Paterson’s poem invites us into a bigger vision of creation. This ‘talking book’ challenges us to imagine all the extent of creation that our brains can become dulled to in the midst of routine and everyday concerns. It’s a refreshing, and to some, a scary experience, ending in that mysterious promise of the ‘so many things’ hidden from you. There is something very human in this – the ignorance, the wonder, the conversational tone. The reader might be reminded of the Total Perspective Vortex of Douglas Adams’s Restaurant at the End of the Universe, a mindboggling machine that gives you ‘just one momentary glimpse of the entire unimaginable infinity of creation, and somewhere in it a tiny little mark, a microscopic dot on a microscopic dot, which says, “You are here.”’

*

Contemporary poetry brings with it its own challenges. The fashion is nowadays for poetry that is so ‘difficult’ to read you have to really sweat out a meaning, or an immediately appreciable domestic poem that refuses to indulge any mystery. The temptation for Christians might be to turn away altogether or to anthologies of Christian poets. I have suggested a way of approaching poetry that emphasizes its humanness: the millions of poems out there waiting to be read each encapsulate a fleck of someone’s life. As Christians who believe in the celebration of every human life in its fullness we are positioned to be excellent readers of all types of poetry: poems do not have to speak about God in the way that theology does for it to be full of wonder and spiritual stimulation. It is in its recording and celebration of all aspects of human existence that its value lies.

Nathan Koblintz is a member of the Thinking Faith editorial board.

Bibliography

Douglas Adams (1981) The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, London: Random House

Simon Armitage (1992) Kid, London: Faber and Faber Ltd

Scott Cairns, (2009) ‘Idiot Psalms’, Poetry, January 2009, Chicago: The Poetry Foundation

Paul Muldoon (2006) Horse Latitudes, London: Faber and Faber Ltd

Don Paterson (2003) Landing Light, London: Faber and Faber Ltd

Don Paterson (2006) Orpheus: A Version of Rilke, London: Faber and Faber Ltd

Jo Shapcott (200) Her Book: Poems 1988-98, London: Faber and Faber Ltd