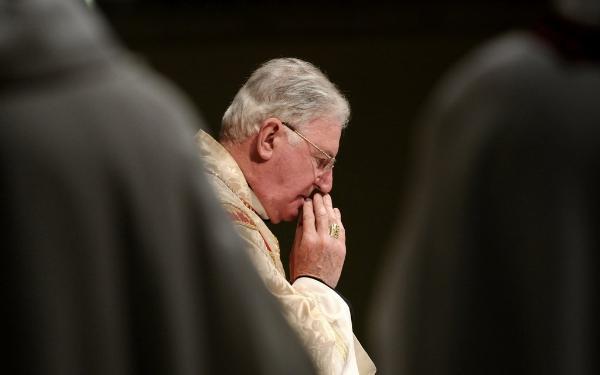

The Holy See has announced that the Apostolic Visitation to the Archdiocese of Armagh will be overseen by Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O’Connor, who ten years ago commissioned a review of cases of abuse in the Church in England and Wales. Following Lord Nolan’s report, the Church has taken measures to prioritise the safety of children and vulnerable adults. Michael Smith SJ, the Safeguarding Co-ordinator for the British Jesuits, explains the policies currently in effect and looks to the further transformation in the Church in the future.

This article builds on that of Fr Brendan Callaghan SJ, published by Thinking Faith. Here, I address two further issues: what is being done in Great Britain to ensure that the situation changes; and secondly, what still needs to be done to ensure that the future could not bring a slide back into the situation as before.

The recent cases which have caused so much anger and distress have shown that people can be fairly forgiving about a priest or religious brother or sister who offends by sexually abusing a child (though they expect him or her to be dealt with effectively), but reserve a particular anger and condemnation for the bishop or congregation leader who did not transparently take effective action when an allegation was made. Most of the cases which are being dealt with in Great Britain at the moment are ‘past cases’, in which the abuse occurred a number of years ago. The figures for 2007 – the last year for which the figures are broken down by the year in which the abuse is alleged to have occurred[1] – show that in England and Wales, out of 53 referrals to safeguarding co-ordinators (note that a referral is not necessarily a case of actual abuse), ten related to that year, another eight to the earlier years of this century, a further 22 to the 70s, 80s and 90s, and the remaining 13 to the 60s or earlier.

It’s not really surprising that cases that arose all those years ago should have been mishandled by what might be referred to as the Catholic Church management. Child sexual abuse only became a public issue of concern in the United States in the 1970s, and in Great Britain around ten years later, and it was even later that anyone really understood its psychology and how it should be dealt with. The watershed in Great Britain was the passing of the Children Act in 1989. It was then that awareness grew of the presence of abuse in our caring provision, and of the many difficulties involved in dealing with it, especially that the sexual abuse of children is so compulsive that there is little likelihood of a change of behaviour on the part of the abuser. Before that awareness grew, church leaders gave the offenders some good advice, perhaps advised confession and more prayer, and then sent them to a different parish for a fresh start. The fresh start certainly happened, but not the one that was intended. It was when these same people cropped up again as repeat offenders that anyone realised just how badly things had gone wrong, and how misguided had been the management of these previous cases.

Around the year 2000, Cardinal Murphy O’Connor was accused of having previously mishandled a case in this way. In fact, there was not much evidence that he had, but he decided to try to sort things out once and for all. He asked Lord Nolan to chair a commission with a brief to decide what the Catholic Church in England and Wales needed to do to deal effectively with these issues. The Nolan report made a number of recommendations, including the establishment of a national body to ensure a single set of policies and good practices throughout England and Wales, and that the Catholic Church should become a beacon of excellence in dealing with abuse. Crucially, this national body would be led by a lay person, managed by a largely lay commission, and all the commissions which dealt with case referrals in dioceses and religious orders would consist mainly of lay people drawn from professions that regularly dealt with cases of abuse. Bishops and congregation leaders, their deputies, and all members of the trustees of the dioceses and religious orders, were excluded from these commissions. It wasn’t just that the trustees and other leaders had a conflict of interest between preserving their assets and reputations, as against listening with care and sensitivity and giving practical help to the victims of abuse; religious leaders would also be spared the conflict of being the person entrusted with the pastoral care of their priests or religious, and of simultaneously being the tough and unbiased disciplinarian of those same people when they were accused. The price of this separation of roles was that they would have to learn to accept the recommendations of their commissions in the actions needed to deal with accused clergy and religious. These largely professional commissions also took on the responsibility of training church workers for their roles and in how to create safe environments for everyone in all the works the Church does. And they brought their experience and insight to the task of trying to do whatever could be done to help victims come to terms with their distress. And so in every parish and every other significant work of the Catholic Church in England, Wales and Scotland there is a link person who knows how to manage the screening of church workers, how to monitor the implementation of safe working practices, and how to refer allegations and concerns to their commission. There are similar systems in some other parts of the world too. And the system is working well: cases are dealt with professionally, transparently and quickly; there are sound safeguarding polices in almost all church works; and good quality training is continually provided. It’s not as good as it would be if there were no abuse, but it’s as good as a human institution is likely to get.

But, in the long term, it’s not yet reliably safe.

It has been said that now that there are successful working systems throughout the Church, people in church management can relax. Cases will be properly and transparently dealt with, good policies will be implemented, and people will stop attacking us. But what of the badness of heart which made these supposedly holy and responsible people abuse the smallest and weakest clients? What of the authorities who didn’t deal with it effectively? To tackle that, we have to consider the culture which pervades our Church.

In his previous article on this topic, Brendan Callaghan wrote a sentence which he realised would make people angry, at least until they thought about it. This article also has a sentence with the same potential to make people angry: the Church is not just the pope, maybe with the bishops, it is not even all the clergy, but all the people who belong to it; and it’s every one of the people who belong to the Church who must share in the responsibility for the culture which made the sexual and physical abuse, and the subsequent cover-ups, of young or vulnerable people possible. This is not a cynical attempt to shift the blame onto the laity; please read on to see why we are all sharers in that responsibility.

A small review of recent abuse cases within the Catholic Church threw up a remarkable fact: that in almost all cases of abuse by clergy and religious, whether sexual or physical abuse, there were people who must have known what was going on, or possibly were terribly naïve, or even colluded in the abuse. Here is an example of this, basically true but very much modified to keep people’s private lives private. A priest ran an altar servers group, and once a week they would have a meeting. Some of the more distant children were picked up by the priest in his car. In one case he would drive up to the house, and the mother of the eight-year old altar server would put his coat on him and make him go off with the priest. The young boy hated this. He was clearly desperately afraid, so much so that one day he wet himself in his terror. His mother took him upstairs, changed his clothes and sent him off with the priest, who took him to the park as usual, sexually abused him as usual, took him on to the altar servers’ meeting, and then afterwards brought him back. The key question here is: what did the child’s mother think was going on? Could she not understand and interpret her own child’s terror?

Whenever questions like this are asked, the answer given is along the lines of: it is because of how priests were looked up to, and that no-one would question what a priest thought should be done. The status of a priest was so high that what he said was law, and he was always right. This exaggerated status of the priest was of course given to him by the laity, but they would say that the priest and other hierarchy demanded it. That is certainly true. It is equally true that while that culture persists in the Catholic Church, the problems of abuse by clergy and religious sisters and brothers will not be solved. And that is why people are so angry when church workers abuse children and vulnerable people – they were entrusted with status, authority and power, but they used them to have their way with vulnerable people, and to prevent discovery of their misdeeds.

Every member of the Church has a responsibility for the culture of the Church, but the problem is that we leave it to one small section to establish it. Think of the way that in England, for example, cabinet members are held responsible when some poor child is abused when more adequate social services could have intervened, and compare that with the silence and secrecy that have hitherto characterised the response within the Catholic Church to abuse by clergy and religious. Those three seducers – status, authority and power – have supplanted the humble service of authority called for by Jesus Christ. A little gospel meditation on the criticisms made by Jesus Christ of the religious authorities of his time will show how many of them could be made of the religious authorities of our Church and in our day.

We need to change this culture where it exists in our Catholic Church. Such a shift of culture, if the majority of the members of the Church insist on it, would transform the Church’s way of working, and introduce to the Church authorities a sense of accountability for the Church they have created.

The new systems introduced since Lord Nolan’s report have been very effective in the parts of the international Church where they are applied, and some other parts of the Church have different and equally effective systems. Such policies counteract, to some extent at least, the tendency of the Church to disown the abuse or the abusers, and recognise the duty of the Church to try to help those who have been abused. They also counterbalance the right and proper attitude of religious authorities who have to care for and defend the priests and religious entrusted to them. But precisely because the safeguarding commissions, or their equivalent, are separate from the management of the Church, whether the hierarchy or the trustees of dioceses and religious congregations, there is a danger that we will think that the problem is sorted and someone is dealing with it. There are few signs at the moment that the fundamental shift in culture, which is needed within the Church if future generations of vulnerable people are to be safe, is actually occurring.

People who deal with these cases notice that the real anger is not with the priests and religious who abuse; they are human and do not leave their human and sinful tendencies behind when they join. The real anger is reserved for the leaders of dioceses and congregations who did not deal effectively with cases that came to their attention. Once again we are led to challenge the culture from which they operated.

All of us who are members of the Catholic Church have to take on our responsibility to establish the culture in the Church which Jesus Christ taught us. If we can do that, the Church will have moved forward in its accountability to all its members. If we don’t then all of these problems will still be with us in twenty years’ time.

Fr Michael Smith SJ is the Safeguarding Co-ordinator for the British Province of the Society of Jesus.

[1] Cf. www.csas.uk.net – Documents; subsequent annual reports are prepared by the National Catholic Safeguarding Commission, and are at www.catholicsafeguarding.org.uk/documents.htm