The Feast of the Ascension strikes many Christians as the poor relative of the two rather bigger celebrations which top and tail the long and joyful season of Eastertide: Easter itself, and Pentecost. But Damian Howard SJ ascribes to this feast the utmost significance. What are we to make of the story of Jesus being taken up into a cloud, an episode that not only sounds like mythology but also violates our modern sense of space?

In between our celebrations of the Lord’s Resurrection at Easter and of the gift of the Spirit to His disciples, the ‘birthday of the Church’ at Pentecost, we observe another feast: the Feast of the Ascension. For all the memorable imagery that the story of Jesus’s ascension into heaven evokes, it still strikes many Christians as a rather curious episode. To put it crudely, had Jesus simply ascended vertically into space we would by now expect him to be somewhere in the outer reaches of the solar system, a thought that is hardly an aid to Christian devotion. Yet the event of the Ascension, which appears in both the New Testament books authored by Luke (his Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles), serves as the narrative lynchpin of the grand story told by scripture. It is, as one scholar argues, the culmination of every biblical event leading up to it and the condition of the drama that follows it.[1] To understand why this is so will take a little explaining.

A good way to begin would be to ask yourself a question: what, in a nutshell, is the core of the New Testament message? There are doubtless as many answers to that question as there are Christians, but most of them would probably involve one or more of a bundle of ideas: resurrection–reconciliation–new life–triumph over sin and death, all very good, very Eastery answers – and all, incidentally, very much about us human creatures. The centrality of these notions to most Christians explains both why Easter and Pentecost are so important to us and why the Ascension is not. Easter and Pentecost can be quickly established to be all about us: the promise of forgiveness and new life for us, the gift of the Spirit to us. It is not quite so clear what the Ascension has to offer us? The best answer I have been able to come up with is that Christ’s withdrawal brings about a new mode by which Christ can be present to us, intimate, yet universal and ‘interceding for us at the right hand of the Father’.

If you were to ask the same question to the New Testament scholar, N.T. Wright, you would be given a subtly different response, one that puts centre stage someone other than us. For Tom Wright, the core truth of Christianity is that Jesus, and hence God, has become King. The crucified Nazarene has been raised by God to be the universal Lord. Christ’s rising from the dead is not in itself the end of the story but a vitally important part of the trajectory that takes him to his heavenly throne. Wright’s interpretation hardly denies the importance of resurrection; it just sees it as part of a bigger picture. Jesus is raised to be King.

All of which has serious implications for Christian belief and practice. If we were to think very schematically, we might say we have two styles of Christian living here: let’s call them Resurrection-Christianity and Kingdom-Christianity. (I am sketching here ‘ideal types’ for the sake of reflection and these should not be taken as applying to any individual or group in particular, still less as criteria for some kind of orthodoxy.) Resurrection-Christianity would focus, obviously, on the Resurrection, on the fact that Christ has overcome death and won eternal life for those who believe in Him. Kingdom-Christianity is more attentive to the arrival of the Kingdom of God, in other words a state of affairs abroad in the world, such that a new source of power and of ultimate authority is enabling and challenging human beings to allow themselves to be transformed, to receive ‘eternal life’ in the here and now. The two styles are hardly opposed to each other but their focus is appreciably different.

What makes Kingdom-Christianity so convincing an interpretation is the way it makes sense of the whole narrative of the Bible by offering a ‘crowning moment’ in the shape of the final resolution of an expectation spelt out in a spectacular apocalyptic scene by the prophet Daniel (7:13-14):

I saw one like a human being

coming with the clouds of heaven.

And he came to the Ancient One

and was presented before him.

To him was given dominion

and glory and kingship,

that all peoples, nations, and languages

should serve him.

His dominion is an everlasting dominion

that shall not pass away,

and his kingship is one

that shall never be destroyed.[2]

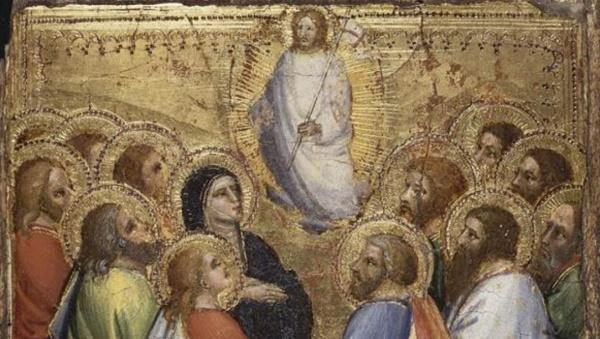

Here, the coronation of the ‘one like a human being’ (the original expression is translated literally as ‘one like a Son of Man’, from which you can deduce whence Jesus derives His favourite way of referring to Himself) is presented exactly as an onlooker in heaven would enjoy the scene. It is a dream-vision, an imaginative rendition of the deep, hope-filled aspiration of faithful Jews, suffering persecution at the hands of an enemy so powerful they could scarcely envisage ever overcoming it. The Ascension, Douglas Farrow points out, is quite simply the very same event as viewed from the earth, the Son of Man setting out on His journey to take up His throne alongside the ‘Ancient One’.[3]

Hence, in the Ascension we see the mystery alluded to in the Hebrew Bible acted out in full view of the disciples. You can see now that the Ascension is no quirky interlude between Resurrection and Pentecost but a dramatic consummation that makes sense of them: the Resurrection is the beginning of Christ’s heavenly journey, Pentecost the echo on earth of heaven’s jubilation at his coronation. The Ascension is crucial, not decorative.

Farrow defends this view of the centrality of the Ascension from the understandable and legitimate anxiety that it downplays resurrection hope as an end in itself:

In the Bible, the doctrine of the resurrection slowly emerges as a central feature of the Judeo-Christian hope. But if, synechdochically, it can stand for that hope, the hope itself is obviously something more. Resurrection may be a necessary ingredient, since death cuts short our individual journeys, but it is not too bold to say that the greater corporate journey documented by the scriptures continually presses, from its very outset and at every turn, towards the impossible feat of the ascension.[4]

So Kingdom-Christianity in no way cancels out or negates Resurrection-Christianity: it includes it but situates it in a bigger picture and it is a picture that does not have us at the centre, with our desires and hopes, but the person of, if you like to think of it like this, King Jesus.

In his book Surprised by Hope,[5] Tom Wright works out some of the consequences of what is for many a surprising angle on the Biblical story. The problem is not that Resurrection-Christianity (he does not use the term) is false. Rather, it is that if it becomes detached from its original moorings in the proclamation of Jesus as King, then it can drift into something lesser. An example is the way many modern Christians have come to think that the point of Christianity is about ‘getting to heaven when you die’. A Christianity rooted in its original proclamation of the Kingdom of God is not in the first place about life after death, but very much about life in the here and now under the new conditions of God’s reign (which is also not in any way to deny life after death!). If it totally loses its anchor in the Kingdom proclamation, an exclusive concern with resurrection has been known to see this world as a decadent and evil place without hope; salvation begins to look like escape. This is a Gnostic tendency to which Christianity has long been vulnerable. For Wright, the time has come to get back to the original Kingdom-Christianity of the Bible with its confidence in the resurrection of the body, its utter Christ-centredness and its concern for the mission of Christians to help transform the world in accordance with the in-breaking Kingdom.

I must confess both to excitement about Wright’s work and also to a certain perplexity. The excitement springs from the plausibility of his biblical interpretation, from the stress he puts on the Gospel as a God-event rather than the transmission of some new information, and on the implications of all this for the way we think about Christian action and witness in the world. But my perplexity is twofold. First, Wright is suspicious about a great deal of the Christian tradition as it has come down to us over the years. He regrets the medieval corruptions that set in, entailing the loss of the ‘real narrative’ of the Kingdom, until, that is, modern exegesis came into existence. An evangelical Protestant like Wright is entitled to think like that, of course, even if it puts a Catholic on the back foot. But is Christian tradition so badly in need of correction or has it, perhaps, managed to hang on to the Kingdom-story rather more than Wright allows? After all, leaf through any hymn book, Protestant or Catholic, and dozens of images of kingship will jump out at you. But still, Wright might say, these may not correspond to the way people actually think and act in their religious lives. Maybe there is a case to answer here.

The second difficulty is that my modern imagination rather baulks at the thought of Jesus sitting on a throne as King in heaven. It’s a fine metaphor but in what sense does it represent a state of affairs? My mind is uneasy with what sounds like mythology and I find myself restlessly wanting to ‘demythologise’ it, to translate it into categories more related to my way of seeing the world. The problem is that the Ascension is essentially an ‘is’ statement whereas demythologising usually ends up with ‘ought’ statements like saying that ‘living in the Kingdom of God’ really just boils down to living by ‘Kingdom values’ or, ‘building the Kingdom’ by being good citizens, speaking up for the victims of injustice and behaving in an ecologically responsible manner. If that is the ‘cash-value’ of the doctrine of the Ascension, then it seems to have made no real difference. Yet the only alternative would seem to mean fixating on a rather literalist interpretation of the doctrine itself; if my (or your) imagination cannot cope, that’s just too bad, because that’s how it is…

An answer to both perplexities comes in the shape of the Spiritual Exercises of St Ignatius Loyola. What I see in his famous itinerary for a 30 day transformative retreat experience is a playing out of precisely the kind of spirituality that flows naturally from the Kingdom narrative: not one of resurrection as an end in itself (though resurrection is very present) but a vivid engagement with Christ, the Eternal King, and a focused and prolonged imaginative effort to contemplate the world under the aspect of the Kingdom of Christ and to discern in depth the difference that this truth makes: i.e. that it calls me to become a servant of Christ’s mission.

There is some irony in making this point. Everyone who has ever made the Exercises knows full well Ignatius’s fondness for regal and military metaphors. People often assume that behind it is Ignatius the (minor) nobleman harking back nostalgically to his time in the Spanish court or soldiering against the French. Yet Ignatius was no sentimentalist. If he used kingly language to speak of Jesus it was quite simply because he knew Jesus as a King.

In this he was helped by the standard, even ubiquitous iconography of the Middle Ages. One of the most common depictions of Jesus throughout the period was the eschatological Christ seated on a throne, surrounded by an oval aura called a mandorla and the four apocalyptic beasts. This figure, known as the maiestas domini, adorns many a Cathedral tympanum, reminding those entering below that Christ is indeed their King here and now. This Christ was majestic and powerful, not entirely dissimilar to the eastern Christian icon of Christ pantokrator, Lord of all. The mandorla was significant too, an unmistakeable reference to the birth canal. The figure of the King in the mandorla, the Kingdom in the very process of being born, echoes the Lord’s prayer: ‘thy Kingdom come!’ It is a dynamic image of God’s Kingdom coming to us as we look on, a reminder that if the Kingdom is indeed already a reality, nevertheless it has not yet fully arrived. It still has something of the subjunctive about it.

Ignatius, judging by the language he uses to speak of Christ in the Exercises, took this icon as his preferred depiction of the Lord. Whenever he imagines himself standing before God, offering himself for service in whatever way God will decide, he speaks of God/Christ as ‘the Divine Majesty’:

Then I shall reflect within myself and consider what, in all reason and justice, I ought for my part to offer and give his Divine Majesty, that is to say, all I possess and myself as well… (Sp Exx 234)[6]

The most important and transformative exercises are preceded by an invitation to imagine Christ as King and to allow oneself to enter into the scene of that image, adopting the behaviour appropriate to it:

how much more is it worthy of consideration to see Christ our Lord, the eternal king, as to all and to each one in particular his call goes out: ‘It is my will to conquer the whole world and every enemy and so enter into the glory of my Father… (Sp Exx 95)

And:

Here will be to see myself in the presence of God our Lord and of all his saints that I might desire and know what is more pleasing to His Divine Goodness. … here it will be to ask for the grace to choose what is more for the glory of his Divine Majesty and the salvation of my soul. (Sp Exx151-2)

Two vital clues suggest that the link with the Ascension was one Ignatius would have made himself. In the ‘Fourth Week’ of the Exercises, which deals with the Resurrection of Christ, Ignatius offers for meditation no less than 13 appearances of the Lord, including one to Paul which would have taken place after the Ascension. But he insists that it is the Ascension that should be the final mystery of the whole retreat to be contemplated. For Ignatius this is no mere detail, no pious addition to the list of biblical incidents but the highpoint, the climax of the whole movement of Christ that brings him to the divine throne before which he stood repeatedly seeking God’s will for his life. The other detail comes from an autobiographical incident that took place when Ignatius was on pilgrimage in Jerusalem. He was about to be expelled from the Holy Land by the Franciscan authorities but before heading for the coast he was desperate to do one last thing: to revisit a particular site from the pilgrim’s itinerary, the place where, tradition has it, Jesus ascended into heaven. Bribing the guards with a pair of scissors, of all things, Ignatius managed to get up to the Mount of Olives where he could check the exact position of Christ’s footprints before He was taken off into the cloud.

So, with regard to my first perplexity, it is clear that Ignatius at least, one of the Catholic tradition’s most brilliant and influential spiritual masters, is an unabashed exponent of Kingdom-Christianity. If you know anything about his life that observation will ring true; he was above all a man who desired to let God’s glory shine out here in the world by living his life as a divine mission. Knowing this, one could never say blandly that the tradition of the Church simply lost sight of the central significance of Jesus Christ as universal King. Indeed, it seems to have maintained it with clarity and vigour.

Ignatius has also relieved my second perplexity considerably, the anxiety that simply proclaiming the kingship of Christ as a literal state of affairs does not seem to get us very far. Appropriating this deep truth, as Ignatius’s life shows, requires a very special human faculty, one that Ignatius was forced to deploy by the very forces which were undermining the ‘Kingdom’ in his day. For at the time he is writing, the image of the Divine Majesty was facing a major crisis. This was thanks to the impending demise of that ancient, traditional cosmology in which the image of Christ as King in heaven made some sense. By the end of the 15th Century the new sciences and the successful circumnavigation of the globe had put that picture under severe pressure. Politically things were changing too. A united Christendom had been evidential warrant to the notion of a civilisation united under the rule of Christ. But now, under the impact of the Reformation, Christendom was breaking up, making it all but impossible to conceive of Christ as King of the universe. This is the decidedly inauspicious climate in which our young Basque finds himself not only drawn to the maiestas domini but also sensing its urgent appeal. I imagine him gazing longingly at some cathedral portal after Mass, on fire with the love of God and aware that, despite all the contradictory desires that filled his heart, it was only in the service of Christ’s mission that inner unity and purpose in life could be achieved. He must have seen depicted in this image a process, a dynamic by which human beings could allow order to be drawn out of the chaos of their lives. He understood that the only way to unleash the transformative power of the Kingdom was not merely by assent to a purported state of affairs but by the deepest possible imaginative exploration of what it means to live in the world where Jesus is King. For the key to engaging with the mystery of the Kingdom is, for Ignatius, as for the Spinner of parables Himself, the human imagination.

Damian Howard SJ lectures in theology at Heythrop College, University of London and sits on the Editorial Board of Thinking Faith.

[1] Douglas Farrow, Ascension and Ecclesia (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1999), p. 26.

[2] New Revised Standard Version.

[3] Ascension and Ecclesia pp. 23f.

[4] Ascension and Ecclesia pp. 26-7.

[5] London: SPCK, 2007.

[6] This and all passages from the Exercises are taken from the translation of Michael Ivens, Understanding the Spiritual Exercises (Leominster: Gracewing, 1998) p. 174.