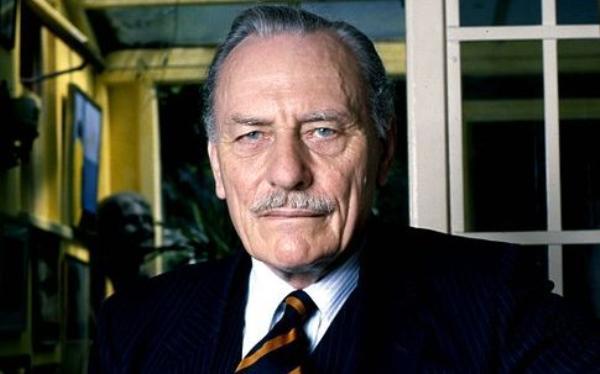

The 100th anniversary of the birth of Enoch Powell on 16 June has provided an opportunity for commentators to assess the lasting reputation of a man who became an infamous figure in British politics after delivering a single speech. Joe Egerton presents a paradox at the heart of Powell’s career: the same man that delivered the ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech was a devout Christian.

On the night of 16 June 1912, a baby was born in Birmingham. The thunder that night was an omen. At half past two on the afternoon of 20 April 1968, in the same city, that baby – now a leading member of the Conservative Shadow Cabinet – rose to his feet to deliver one of the most notorious speeches in modern British history. One of the passages caught by television was this: ‘We must be mad, literally mad as a nation, to be permitting the annual inflow of some 50,000 dependants, who are for the most part the material of the future growth of the immigrant-descended population. It is like watching a nation building its own funeral pyre.’ The cameras did not record the line that was to give the speech its name: ‘As I look ahead I am filled with foreboding. Like the Roman, I seem to see “the River Tiber foaming with much blood”’.[1]

A Christian and a racist?

Enoch Powell’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech led to his being denounced as a racialist. He was summarily dismissed from the Shadow Cabinet. Two years later, when Powell pledged to bring about an effective halt to immigration in his election address to the voters of Wolverhampton, Tony Benn declared, ‘The flag of racialism which has been hoisted in Wolverhampton is beginning to look like the one that fluttered over Dachau and Belsen.’[2] But unlike Hitler and his accomplices, who planned to destroy not just Judaism but Christianity, Enoch Powell had undergone an Augustinian conversion to Christianity in 1949:

One night in Wolverhampton I was coming home from the station. The bells of St Peter’s were ringing for evensong and I went in. It was the first time I had been into a church for worship, to a service, for fifteen years or more. I sat down in a dark corner, just by the south door, hoping I wouldn’t notice myself, because I didn’t know what I was doing and I was rather ashamed of it. As I listened, the language of it all came back to me.

Robert Shepherd, in his biography of Powell, described the sequel: ‘The following Easter, Powell told himself, “Look, you can’t stay here, you either go back or you go forward.” He knew he could not go back, so “forward I went” and at 6.00AM on Easter Sunday 1950 he took communion’. There then follows this assessment: ‘his devout belief in Christ and the resurrection as the prerequisite to salvation were to remain essential to his private being.’[3]

Simon Heffer, in his biography, provides an interesting insight into what we might consider to be an Ignatian dimension of Powell’s practice, when he quotes him saying:

Over and over again, and often in the course of a day, I am conscious in my life as a politician of committing the sins of hatred, or envy, or malice; and I am conscious of the command operating, to some extent at any rate, upon my nature which not merely forbids these things but equates them with death.[4]

However, Powell’s views on immigration were condemned as ‘unchristian’ by Sir Edward Heath; and some Anglican bishops complained when Powell’s body was received to rest overnight in Westminster Abbey because of his part, as they saw it, in exacerbating racial tension.[5] We are confronted then with a paradox: how can the same person be a devout Christian (albeit of rather heterodox views[6]) and a racialist?

Powell was no racist

Ian Gilmour wrote of the Rivers of Blood speech that Powell may have made a racialist speech, but he was not a racist.[7] The evidence seems to support this view.

For example, in 1944, Powell was serving in India and on a visit to Poona refused to stay in the Byculla Club when it refused to admit a fellow officer, General K M Cariappa, who later became first Chief of Staff of the Indian army.[8]

And in 1959, with an election imminent, Powell put at jeopardy the prospect of a return to office with a formidable denunciation of the Macmillan government’s handling of the death of eleven Kenyan detainees at Hola. He spoke late in the debate, and was affronted by a fellow Tory MP’s suggestion that the Africans were ‘sub-human’:

I would say that it is a fearful doctrine, which must recoil upon the heads of those who pronounce it, to stand in judgement on a fellow human being and to say, ‘Because he was such-and-such, therefore the consequences which would otherwise flow from his death shall not flow.’[9]

Neither of these interventions would be expected of a man labelled as a racist.

So how did Powell make the Rivers of Blood speech?

The Birmingham speech undoubtedly contained passages that shock. Powell, however, convinced himself that he was simply setting out Conservative policy. Indeed the actual policy prescriptions – the decision to restrict immigration, the decision to present a reasoned amendment to the Race Relations Bill – were Conservative policy. It was, however, his language that caused the outrage.

Powell was in fact addressing a very serious problem. The meeting’s chairman, the Conservative MP for Hall Green Reginald Eyre, said later that he had detected early in the speech a stirring in the audience, which included some of the most competent figures in the West Midlands: ‘They knew that a major politician was giving voice to their long held fears.’

What were those fears? Without doubt that major towns and cities were heading fast for a segregated society that many, including Powell himself, had in the 1960s seen in America. It was only in 1964 that President Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act and, although we now see the successes of the drive against segregation, fifty years ago the legislation seemed a recipe for strife, not peace. The situation there appeared completely impossible and it was understandable that those who, like Powell, had visited America should be determined to prevent the same evils here.

Learning from Powell’s error

‘Poor Enoch,’ Iain Macleod once remarked to the political columnist Alan Watkins, ‘driven mad by the remorselessness of his own logic.’ The Thames has not foamed with blood; England has not been torn apart by another civil war; and Powell was simply wrong to assert that mass immigration would lead to civil war. But his reputation for formidable logic suggests that his error lay not in his reasoning but the premises he started from.

One fallacy that underpinned Powell’s conclusion was his belief that there was no prospect of integration between black and white. At earlier stages in his career, Powell had not believed this; it was only following his first visit to America in 1965 that he seems to have reached a different conclusion. But it clearly was a belief that he came to hold. When asked how he would react if one of his daughters married a black man, he replied that he would be far less worried about the future of the country if there were intermarriage.

Another error that led him to despair of integration as a solution was a failure to appreciate that Christianity might prove a basis for unity. This is tragic, given that Powell had earlier recognised what a powerful force Christianity could be. ‘It may appear an unpractical assertion, but it is an arresting and undeniable one, that if everyone were a full member of the Church, the class war and that mutual fear and envy that is socialism would instantly be inconceivable’, wrote Powell in the 1950s in an unpublished essay arguing that the Conservative Party needed to give attention to the Church.[10] Powell’s diagnosis of the immigration issue was that it caused fear, so perhaps he could have appealed to the Church as the basis for a solution to the problems of immigration as he saw them, just as he had done for those of socialism.

Not a single subject person

When Powell died in 1998, the chairman of the Association of Black Clergy put out a statement: ‘Powell was not a single subject person and served his country well. Each person stands before God as an equal and deserves the same level of love.’

Although Powell argued steadfastly that bishops and clergy had no authority from the Gospels to preach a social gospel, his record in office and in his early years as an MP in fact shows him to have been an effective practitioner of an approach that Catholics would recognise as part of the Social Teaching of the Church. He was a passionate advocate of priority to housing, because without decent housing there was no prospect of decent family life. He was also willing to reform the treatment of the mentally ill and it should be noted that, despite his reputation for fiscal rectitude, he was insistent that care in the community had to be adequately funded. He was unequivocal on the value of human life and towards the end of his Parliamentary time, on 14 February 1985 Members of Parliament received a letter from Cardinal Hume urging them to support his bill to outlaw experimentation on human embryos created by in vitro fertilisation. A few months earlier he had condemned Margaret Thatcher’s insistence that funds for education be diverted towards the sciences ‘in the interests of increasing national prosperity’. This, Powell declared, was the way to ‘an inhuman and barbarous state’, adding that education was not intended to be useful, but was ‘to the glory of God’.

Enoch the Uncounselled

It is little wonder that even such strong supporters of Enoch Powell’s economic views as John Biffen – who delivered the eulogy at his funeral – regretted the Rivers of Blood speech, or that it ended his friendship with Clement Jones, his long standing friend and editor of the Wolverhampton Express and Star. Powell’s characteristic approach of solitary thinking, and his decision to press ahead with the speech without consulting senior advisers or supporters beforehand, destroyed his career.

Had he been constrained by obligations to colleagues, Powell’s legacy may not be what it now is. Powell in office was a very different man from Powell in opposition. When in office, he was willing to compromise, to work with colleagues; he applied his formidable intellect to practical reality. If Powell had been in office in 1967, and perhaps even charged with finding solutions to the problems posed by concentrations of immigrants in a limited number of towns and cities, the Rivers of Blood speech may not have been made. As a cabinet minister under Macmillan, Powell had shown a complete understanding of the demands of collective responsibility, acquiescing in and even vigorously promoting policies which he was, when freed from the constraints of office, to condemn. Even in opposition, if Powell had been better handled, perhaps by a different leader, the speech may not have been made.

There is an irony in this: in his great, scholarly History of the House of Lords in the Middle Ages, Powell opened by celebrating the importance of politicians seeking advice: ‘the act of taking counsel cannot be separated from the act of exercising authority.’[11] Humans are most likely to do good when we are working together, and are very prone to do things we later regret when we fail to take counsel from our friends. But for one speech which his friends, if consulted, would have warned him not to make, Enoch Powell might have once more become a cabinet minister, achieving in other departments what he had done as Minister for Health, and remained MP for Wolverhampton until 1997. He might never have crossed the water to Ireland, an aspect of his career which I have not had space to discuss. If that high intelligence, formidable integrity and compelling oratory had been harnessed to the practical work of running departments of state, we might all have benefitted. As it is, the words of Enoch Powell, heavily tainted by one ill-fated address, have not been forgotten. We might ask whether he served us any better than Ethelred II, a king whose disastrous reign ended in 1016 with the occupation of kingdom by the Danes and of whom Powell himself wrote: ‘The characteristic which English men remembered most was that he was “uncounselled” (unraed’)[12]’.

Joe Egerton works in the City as Chief Operating Officer of a stockbroker specialising in shares of medium-sized firms. He has lectured at the Mount Street Jesuit Centre.

[1] It was not in fact the Roman who saw the River Tiber foaming – it was the Sybil, whom Aeneas consulted: see Virgil, Aeneid, VI.

[2] Tony Benn – who was a good friend of Enoch Powell’s – later told his biographer ‘I did go over the top with “Dachau and Belsen.”’ But he added that he did not regret having taken on Powell ‘on the question because his influence has been wholly pernicious.’

[3] Robert Shepherd, Enoch Powell (London: Hutchinson, 1996), p. 77.

[4] Quoted in Simon Heffer: Like the Roman: the life of Enoch Powell(Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1998) p. 138. The quote comes from a conversation with Malcolm Muggeridge in 1970.

[5] Powell had for many years served as Church Warden at St Margaret’s Westminster and as such had an entitlement to be received into the Abbey; Canon Gray, the Rector of St Margaret’s, publicly condemned ‘chief pastors who were adding quite thoughtlessly and insensitively to [the family’s] grief and pain in their time of bereavement.’ (Heffer, p. 952)

[6] Towards the end of his life, Powell produced a translation and commentary on St Matthew’s Gospel that argued that St Matthew had falsified an earlier gospel in which Jesus had been stoned, substituting a crucifixion for political reasons. In the Spectator, the writer on religious matters and one time Jesuit, Peter Hebblethwaite, judged that Powell's book 'is much more subversive of the Christian message than anything David Jenkins, the sometime Bishop of Durham, has hinted at.' (David Jenkins had apparently described the resurrection as ‘conjuring with bones.’)

[7] Ian Gilmour and Mark Garnett, Whatever happened to the Tories? (Fourth Estate, 1997), p. 236.

[8] Shepherd, p. 55; the story is repeated – by Pam Powell, Enoch’s widow – in an interview for a forthcoming book (Evening Standard, 18 June 2012).

[9] Hansard, 27 Jul Col 236: the whole speech repays reading – it was hailed by many as the greatest post-war speech in the Commons. Powell was later to talk of its central theme – Parliament and its Members having a duty – as something that drove him to represent all his constituents, whether in Wolverhampton or South Down, regardless of their origins.

[10] Heffer, p. 134

[11] J Enoch Powell and Keith Wallis, The House of Lords in the Middle Ages (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1968) p. Xi.

[12] Ibid., p. 2.