The recent Danish film, A Royal Affair, is Nathan Koblintz’s choice for our ‘Virtues on Film’ series. Rather than a more traditional and neat filmic portrayal of justice, this Oscar nominee shows us how that particular virtue often needs to be fought for, in what is rarely a trouble-free process. The film’s inter-linked storylines, based on real events, highlight a question: is ‘doing justice’ the same as ‘being just’?

Perhaps more than any other art form, narrative films carry with them their own systems of justice. They set up their own architecture of what is right and what is just, and the storyline is an escalation of tension and conflict, until the good guys win and the bad guys lose. Even in more ‘alternative’ offerings – films such as Napoleon Dynamite, Juno or Donnie Darko – where the heroes may be less-muscled and more eloquent, there is still a very clear line drawn around those who deserve to succeed and those who deserve defeat. Our cinema tickets are the fees we pay to see justice play itself on screen.

Most often, it is the film’s ending that delivers to us our portion of justice. It is hard to think of many mainstream films that have genuinely ambiguous endings – The Graduate is one that comes to mind, as well as some of Lars von Trier’s films. Justice on film requires loose ends to be tied up; it requires a dividing up of some type of good, whether that be love, or freedom, or life itself, amongst its characters, as befits their moral standing. Perhaps the archetypal quest narrative, seen most clearly in The Lord of the Rings, is where justice is so obviously the engine room for the narrative: the hobbits set out to bring the right order of things back to Hobbiton and Middle Earth. Though we can debate whether Gollum/Smeagol ‘gets what he deserves’, it is still clear that he has been through a process of being judged – we can quibble over the sentence he receives, but the story does not allow us to question whether he or not he should be sentenced.

But it is very rare that we get to see the workings of justice – the uncertainties, the dilemmas, the ambiguities, the lack of knowledge. Justice on film is generally delivered at the end of a fist or a kiss. What makes A Royal Affair unusual is that it dramatizes the process of doing a particular kind of social justice.

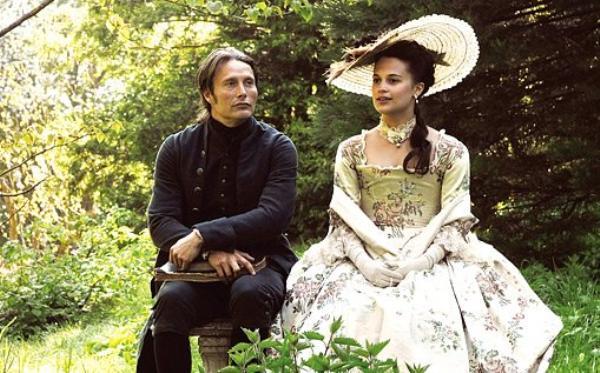

The film, nominated for the Best Foreign Film at this year’s Oscars, is a period piece set in 18th century Denmark. It follows the relationships between the mentally ill King Christian VII, his purchased English Queen, Caroline, and a doctor brought into court to treat him. What sets it far apart from films like The Madness of King George or The Duchess, is the story it tells of how Dr. Struensee, through his friendship with the King and his affair with the Queen, is able to manipulate power in order to implement throughout Copenhagen the social reforms that the Enlightenment thinkers desired: universal rights to medicine, land and education; freedom from serfdom; the liberalization of speech and society. To anyone involved in politics at any level, the court scenes are recognisable, despite the period differences: vested interests, uneasy alliances, favours that are expected to be returned. Based on a true story, the action takes place in the years before the French revolution – this Danish precursor is less bloody but no less revolutionary in its ideas. This period of history is the birth of so many of the ideas of justice that we now hold to be commonplace: the equality of men and women before the law, the expression of basic human rights.

A Royal Affair succeeds as a film because it is able to tie up both the emotional storyline of the relationships between King, Queen and Dr. Struensee, and the storyline of the latter’s relationship with pragmatism and idealism. As a drama it shows us an example of what happens when one attempts to implement a strong idea of justice in a world that is hostile to or unready for it.

One of the core questions is whether justice should be measured as a way of being, or in its concrete manifestations. Justice must be measured, in order that we can see accurately where we are, and what needs to be done – as children when we say ‘that isn’t fair’, or when as adults we insist that ‘justice has not been done’, we are making comments on the progress, or lack of it, towards a just world. Dr. Struensee sees justice purely in terms of outcomes, of achievements: he wants the inoculation programme in Copenhagen spread out to cover the whole of the city, not just the rich areas; he wants every child to be educated; he wants censorship removed from every newspaper. His measurement of justice in the country is based on how widespread his reforms can go, on how many people are affected. He is the classic activist: concerned with ends, with visible justice.

In his fixation on consequences he draws more power to himself, convincing the King to abolish the rest of his council so that he can draw up any laws. On his first visit to court, Dr. Struensee notices how the King is a mere puppet, signing off the decisions of the council. His treatment focuses on giving the King more confidence to challenge their views; but as the doctor becomes more powerful, the King once again reverts to a servant, albeit to a different master. Dr. Struensee‘s affair with the Queen does not affect his desired outcome in terms of social reforms, and in fact could be justified by some of the Enlightenment’s more excitable writers (freedom from marriage, from all social bonds), but it is clear that this is not justice being done to her husband. Dr. Struensee battles with those twin demands: to be a person who creates justice; and to be a person who embodies justice. His failure in the latter is inextricably linked to his ultimate failure in the former.

This difference between what we might call ‘personal justice’, which deals with the relationships with those closest to us, and ‘social justice’, which deals with the relationships with those we may never meet, is of course a false difference. But however false it may be in terms of the spirit or the intellect, it is still a very real divide that we often encounter in our lives. We need not think further than our own parishes to see examples of generosity and concern for social justice in faraway countries matched by failures in personal justice to those sitting on the same pew.

What prevents us from unleashing our desire for justice to all, regardless of who they are, is often tied up with the question of deserving and undeserving – ‘to each his due’ is a phrase that has much to answer for. Attempts at justice in this world are so difficult when broached on a wide scale, particularly in democracies – the need to balance consensus with protection for the minority; the difficulty in obtaining and communicating accurate information on and to people thousands of miles from each other; creating enough of a sense of shared identity amongst disparate people that they are able to be motivated to consider a stranger as a brother or sister. The easiest shortcut to justice is to decide who deserves what, which boils down to those whose behaviour matches the demands of those in power being classified as ‘deserving’. In political terms we are often encouraged to make judgements about goodies and baddies like a film audience – we are told to look for symbols, to listen for dog whistles. A Royal Affair treats us more intelligently: we see Dr. Struensee facing an ungrateful crowd, despite all that he has done on their behalf. Their anger is not caricatured; through misinformation (released through the easing of censorship laws), they believe him to be an intruder in the court, his betrayal of the King in some way a betrayal of the country. This is not the ungrateful mob of Coriolanus but rather a realistic portrayal of the traps along the way for any who attempt upheaval in the name of good.

The defeat of Dr. Struensee‘s reforms shows the vulnerability of justice as virtue when it is nurtured in isolation. Justice is one of the most exhausting of the virtues to exercise, and it involves so much of what looks like failure and compromise that it can never nourish the human on its own. There is not even the guarantee of social approval that, say, a courageous woman or a temperate man is likely to receive: as A Royal Affair shows, justice will always involve controversy and criticism, even if it is just your children accusing you of favouritism. It is always sad to see divisions between those who contemplate and those who act for justice – although epistemologically the division is again a false one, in real terms the demands of time and careers mean that people tend to fall into one of the categories. In our Church the question is whether our theologians are rooted enough in the exigencies of the real world, and our activists are rooted enough in fertile theological soil. This makes it even more valuable when people are able to synthesize both action and deep thought.

More importantly, it is where justice is not supported by a life filled with the other virtues that its fragility comes through. Dr. Struensee has cultivated his virtue of justice in its social applications to the extent that it displaces the other virtues and the result is that he loses track of both his goals and his initial vision. His lack of hope and faith, in particular, leave him undernourished and unequipped for the fight.

Nathan Koblintz is a former member of the Thinking Faith editorial board.

‘Virtues on Film’ on Thinking Faith:

The Saving Power of Christian Virtue in The Lord of the Rings by Catherine Hudak Klancer

The Saving Power of Christian Virtue in The Lord of the Rings by Catherine Hudak Klancer

Fortitude in Of Gods and Men by Niall Keenan

Fortitude in Of Gods and Men by Niall Keenan

Prudence in Star Trek by Simon Potter

Prudence in Star Trek by Simon Potter

Faith in High Noon by Karen Eliasen

Faith in High Noon by Karen Eliasen

Caritas in Quartet by Quentin de la Bédoyère

Caritas in Quartet by Quentin de la Bédoyère

Hope in Life is Beautiful by Frances Murphy

Hope in Life is Beautiful by Frances Murphy

‘The Seven Deadly Sins on Film’ series on Thinking Faith:

‘The Seven Deadly Sins’ by Nicholas Austin SJ

‘The Seven Deadly Sins’ by Nicholas Austin SJ

‘Envy’ in Amadeus

‘Envy’ in Amadeus

‘Pride’ in The Talented Mr Ripley

‘Pride’ in The Talented Mr Ripley

‘Lust’ in Shame

‘Lust’ in Shame

‘Sloth’ in American Beauty

‘Sloth’ in American Beauty

‘Greed’ in Shallow Grave

‘Greed’ in Shallow Grave

‘Gluttony’ in Super Size Me

‘Gluttony’ in Super Size Me

‘Wrath’ in Shine

‘Wrath’ in Shine