To many people, last weekend’s beatification of Benedict Daswa, a school teacher from the far north of South Africa killed for his rejection of witchcraft, was surprising. Anthony Egan SJ introduces Daswa and explains why the decision to make him South Africa’s first Beatus was somewhat controversial. What might be the significance of this beatification for the Southern African – and global – Church?

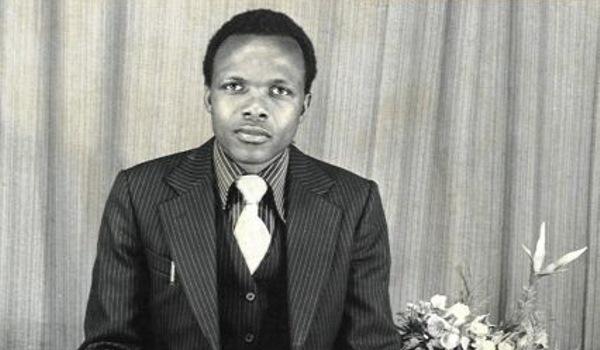

The beatification of Tshimangadzo Samuel Benedict Daswa (1946-1990) on Sunday 13 September 2015 was a first for the Catholic Church in South Africa: our first Beatus, in effect our first candidate for sainthood. The event, celebrated in Tshitanini village, Limpopo Province[1], near where he was stoned and beaten to death on 2 February 1990, drew a crowd of over 20,000 people including Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa[2] and two other members of the Cabinet. Despite it being a very cold day, and the circumstances of Daswa’s death controversial, the mood was joyous.

Benedict Daswa was born on 16 June 1946 in Mbahé, a village in what is now Limpopo. He converted to Christianity as a teenager, was baptised and confirmed in 1963, and qualified as a primary school teacher ten years later. He was acknowledged as an excellent and inspiring teacher. In 1974 he married Shadi Eveline Monyai, a Lutheran, in an African traditional ceremony. Four years later they were married civilly. In 1980, after she converted to Catholicism, the marriage was convalidated in a Catholic ceremony.

A father of eight, Daswa combined his role of parent and educator with increasing commitment to the life of the Church. In his parish he was a catechist, active in liturgy preparation, charitable works and justice and peace. The congregation of Missionaries of the Sacred Heart (MSCs) who served in the district regarded him as one of their most important lay co-workers in building up the Church in an area where many were believers in African Traditional Religion, or remained strongly influenced by it.

This ambivalent coexistence of cultures (not uncommon in Africa) came to a crisis point in early 1990, when on 25 January a number of huts in the village were burnt down by lightning strikes. Many believed this to be the result of witchcraft and decided to consult a sorcerer from a neighbouring village to identify the witch, so as to kill him or her. To do this each member of the village was required to pay R5 (at that time the equivalent of about £1, quite a large sum in a poor, rural community) to remunerate the sorcerer.

Daswa refused to pay the ‘fee’, arguing both that the claim of witchcraft was nonsense and that such beliefs, which would lead to the killing of an innocent person, were immoral. As a Christian and Catholic he would have no part in it. A few days later, en route to a nearby village, he was ambushed and stoned by a crowd. He was then beaten to death with a knobkerrie – a traditional club – and boiling water was poured over his head. At his funeral red vestments, the sign of martyrdom, were worn by the priests and during the homily it was suggested that he had died as a martyr for his faith and opposition to witchcraft.

A popular devotion grew up in the region around him. The MSCs and the local bishop, Hugh Slattery, initiated a cause for Daswa’s beatification and he was soon designated Servant of God. In January 2015, Pope Francis announced that Daswa was to be beatified.

Throughout the process that led up to 13 September, there were a number of controversies surrounding Benedict Daswa’s cause – about the man, the circumstances of his death and the implications of setting him on the path to sainthood.

The first cluster surround Daswa the man. Some object that he lived in what from the Church’s perspective might be called an irregular relationship for six years before he was married in Church. From a narrowly Western perspective this claim might have some validity, but it deserves a closer, more nuanced examination.

Over the last sixty years or so, the Catholic Church in Africa has battled with the degree to which traditional beliefs and cultural practice can be reconciled with doctrine. Increasingly, there has been an attempt to see how traditional beliefs, including marriage practice, may be accommodated[3] as a kind of pre-foundation of Christian values. Traditional marriage contains much that the Church respects, notably its belief in family: traditional marriage stresses the unity of families and the role of communities in supporting a newly married couple. Even such controversial practices as lobola (‘bride price’) – a form of dowry that the groom must pay the bride’s family before they can be formally married – has a positive aspect: it is an ‘insurance’ against infidelity, in that it reverts to the bride if she is abandoned by her husband.

It should be noted, too, that traditional beliefs, including those about marriage, remain strong – even in a rapidly urbanising and secularising culture. Historically, churches in Africa that reject these traditions outright do not gain much traction, particularly in rural communities. The Catholic Church’s commitment to inculturation – accommodation to beliefs that do not overtly contradict the faith, often by seeing allegories of Christian tradition in them (e.g. honouring of the communities’ deceased ancestors as a kind of extension of our cult of the saints) – has been considerable and as a result the growth of Catholicism in Africa has been rapid.

In a sense, one might say that though Daswa’s ‘extended’ marriage might not be an ideal example to the European Catholic understanding, it is neither uncommon nor particularly controversial in the South African context. (Some, looking towards the October Synod in Rome, might even see it as an example of a more flexible idea of marriage that is worth wider consideration).

The second, more difficult, set of controversies Daswa’s beatification raises is the question of African Christian belief, and sometimes participation, in witchcraft. Some have felt that the beatification constitutes a rejection of African Traditional Religion by the Church. This is, I think, mistaken and rooted in the failure to make a number of careful distinctions.

We must disambiguate African Traditional Religion from witchcraft. Similar to the beliefs of First Peoples throughout the world (Asia, Oceania, the Americas), African Traditional Religion is a complex and varied set of beliefs in God, Nature and Humanity’s role in the Cosmos. Many theologians, including but not exclusively African theologians[4], see in these traditions elements that can be reconciled to Christian faith, whether as allegories of belief or the pre-foundations on which to spread the Gospel. Since these reflections – often falling under the rubric inculturation – constitute a growing library of theological thinking[5], I cannot adequately examine them here, but two points need to be noted: first, that the extent to which African Traditional Religion can be accommodated into Christianity is controversial; second, that whatever the Church decides on the former, the integration of such belief is a real part of the African Christian spiritual worldview. With Benedict Daswa we should not see someone who simply rejected his traditional roots but, by a process of intellectual and spiritual re-negotiation, discerned which he could retain with Christian integrity and which he had to discard. In this, I would suggest, he is a model for African Christians today.

Within African Traditional Religion there is a strong tradition that focuses on healing, based on a sophisticated form of folk medicine that draws on indigenous knowledge systems rooted mostly in herbalism (akin to Western and Asian homeopathy) and sometimes in animal sacrifice. All of it has a religious and ritual component. As in Western allopathic medicine, there are specialisations: some healers focus on herbalism, others on dealing with psychic ailments. In some cases there are beliefs that sickness is caused by either offending the ancestors or by sorcery of others. The latter, which does happen, is what constitutes witchcraft per se.

Most traditional healers (sometimes given the offensive term ‘witchdoctors’) are benign. They serve the community. Many are in fact practising Christians. However, a few are what one might call sorcerers – using their skills to harm others, at a price, sometimes using human body parts obtained by murder (so-call ‘muti murders’). As a Christian, Benedict Daswa would clearly have rejected such perversions of belief as immoral – whether he believed they were effective or not.

The problem is that many Africans, including African Christians, believe in the power of witchcraft. And the extent of this belief goes far beyond individual curses. It extends to beliefs that my ill-health, misfortune or poverty may be the result of bewitchment[6]. In areas where knowledge of science is limited it could be advanced as an explanation for natural disasters (like lightning, in Daswa’s community). During the turbulent 1980s and 1990s witchcraft was sometimes a code for demonising and killing opponents in political conflicts – a phenomenon that, it has been noted, was part of the political climate in Daswa’s Limpopo area during this period[7]. To deny the existence of witchcraft in such circumstances could even have been seen as an admission that the denier was himself or herself a sorcerer or in league with witchcraft.

Daswa’s dilemma was clear: though he knew the real cause of lightning, he would be opening himself to accusations that he supported ‘witchcraft’, by rejecting the idea of counter-magic and violence. In addition, as a Christian he believed that it would be a denial of God’s power over evil to use such tools even in cases where it was believed that witchcraft was used.

What then is the Church saying in beatifying Benedict Daswa? I do not see the Church rejecting wholesale African Traditional Religion or even its authentic healing practices. Since Vatican II the Church has respected and seen the value in positive aspects of culture. But it has rejected the idea that culture is an absolute that trumps the Gospel. As the great Protestant scholar H. Richard Niebuhr insisted,[8] ‘Christ and Culture’ need to be in dynamic and critical dialogue, informed one must add by the best insights of scientific knowledge. Daswa’s decision, his martyrdom and subsequent beatification is a validation of what we understand as Catholics to be central to living the Christian life. In this, Benedict Daswa is a model for the universal Church.

Anthony Egan SJ is a member of the Jesuit Institute, South Africa and Chaplain to the University of Johannesburg.

[1] In Daswa’s lifetime this area was the northern part of the Transvaal Province. In 1994 it became the Northern Province. Its name was subsequently changed to Limpopo.

[2] Like Daswa, Ramaphosa is a Venda from Limpopo.

[3] For a recent argument for rethinking Christian marriage in Africa see: Benezet Bujo, Plea for Change of Models for Marriage (Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa, 2009). For a historical view of the question see Adrian Hastings, Christian Marriage in Africa (London: SPCK, 1973).

[4] See, for example: John S Mbiti, African Religions and Philosophy (London: Heinemann, 1990); Mbiti, Introduction to African Religion (London: Heinemann, 1991); Benezet Bujo, African Theology in Its Social Context (Maryknoll NY: Orbis, 1992); Laurenti Magesa, African Religion (Maryknoll NY: Orbis, 1997); John Parratt, Reinventing Christianity: African Theology Today (Grand Rapids: W B Eerdmans, 1995); Aylward Shorter, African Culture and the Christian Church (London: Geoffrey Chapman, 1973); Shorter, Christianity and the African Imagination (Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa, 1996).

[5] See: Aylward Shorter, Towards a Theology of Inculturation (Maryknoll NY: Orbis, 1989); Robert J Schreiter, Constructing Local Theologies (Maryknoll NY: Orbis, 1985).

[6] See: Adam Ashforth, ‘On living in a world with witches: everyday epistemology and spiritual insecurity in a modern African city (Soweto)’, Magical Interpretations, Material Realities: Modernity, witchcraft and the occult in postcolonial Africa, eds. Henrietta L Moore & Todd Sanders (London: Routledge, 2001), pp.206-225; Ashforth, Madumo: A Man Bewitched (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000).

[7] See Isak Niehaus, Witchcraft. Power and Politics: Exploring the Occult in the South African Lowveld (London: Pluto Press 2001), especially pp.130-182; Commission of Inquiry into Witchcraft Violence and Ritual Murders, Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Witchcraft Violence and Ritual Murders in the Northern Province of the Republic of South Africa (Ralushai Commission) (Ministry of Safety and Security, Northern Province, South Africa, 1996).

[8] H Richard Niebuhr, Christ and Culture (New York: Harper, 1951).