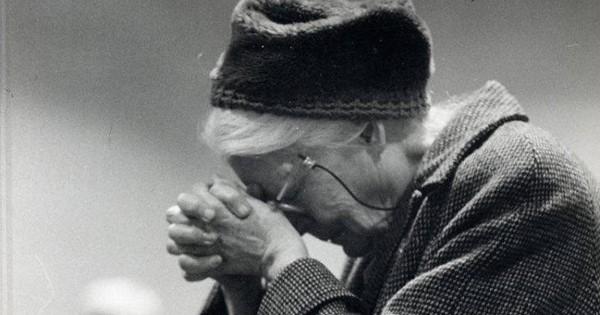

Photo shared via Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Dorothy Day was born 125 years ago, on 8 November 1897. The gospel-based witness to non-violence that she and the Catholic Worker Movement that she founded bore was initially countercultural in both contemporary American society and the Church, but their convictions were ultimately confirmed by the teaching office of the Church. Niall Leahy SJ explores one aspect of the theological foundations of Dorothy Day’s beliefs.

The pacifism of the Catholic Worker Movement

The editorial of the first edition of The Catholic Worker magazine that was published after the US had signalled its intent to enter World War II contained the following statement: ‘We are still pacifists, and our manifesto is the Sermon on the Mount, which means that we will try to be peacemakers.’[1]

The pacifism of the movement’s founders was rooted in Catholic beliefs, which they were not the least bit reticent about stating, but it was also the fruit of experience. The movement’s co-founder, Peter Maurin, had personally experienced life in the French military, and had seen for himself and grieved the odious effects of war. He observed and despised the ‘gradual loss of manners, the bitterness in men’s eyes, the slow development of the impersonal human machine demanded by the high command.’[2] This harrowing experience led him to ask a very difficult question: ‘Why am I, a religious dedicated to winning souls for Christ, caught up in this militaristic system?’

He and the other founding members of the Catholic Worker Movement found the answer to this question in the gospels and the early church fathers; their position was labelled ‘evangelical pacifism’.[3] A seminal article in The Catholic Worker in 1934 by the pacifist priest-educator Fr Paul Hanly Furfey took the form of an imaginary debate between Christ and a patriot. In it, Furfey asserted that the calling to establish God’s kingdom of love and peace took precedence over obedience to the state.[4] Another editorial plainly stated: ‘We are against war because it is contrary to the Spirit of Jesus Christ, and the only important thing is that we abide in His Spirit.’[5] Editorials and articles also drew on the thought of early church fathers, especially St John Chrysostom. Co-founder Dorothy Day wrote: ‘St John Chrysostom says regarding our Lord’s sending us out as sheep among wolves, if we become wolves ourselves, He is no longer with us.’[6]

The Catholic Worker’s brand of pacifism should not be confused with the more common understanding of pacifism, which is quietistic.[7] They were actively non-violent in their pursuit of justice, and they incorporated many proactive elements into their position. During World War II, the movement ran a camp for Catholic conscientious objectors (COs).[8] The Catholic Worker Movement also appealed to the US government to accept all Jews who were fleeing Germany seeking refuge.[9] Their activities extended beyond dealing with the fallout from war: they tried to live in such a way that would reduce the chances of war breaking out in the first place. Apart from not cooperating with activities that supported war, the other ‘weapons’ in their arsenal were living with and working for the poor, and voluntarily choosing to live poorly and simply themselves. Following the rationale that many wars are started for economic reasons, one of the aims of living in a spirit of poverty was to counteract individual and collective greed.[10]

Dorothy Day was also a strong advocate of using spiritual practices to promote the cause of peace. This included personal prayer, availing of the sacraments, fasting and doing penance. In the January 1941 edition of The Catholic Worker, she wrote: ‘If we are not going to use our spiritual weapons, let us by all means arm and prepare.’[11] Towards the end of her life she expressed again the utmost value of prayer: ‘I am convinced that the life of prayer, to pray without ceasing, is of prime importance.’[12] Her assertion in the November 1949 edition of The Catholic Worker – ‘Our activity will be the Works of Mercy. Our arms will be the love of God and our brother’[13] – was not simply an anti-war stance: she was proposing a total way of life, the fruit of which would be peace.

Underlying theology

In addition to the way in which the message of peace found in the gospel and the exhortations of the early church fathers shaped the attitude of Dorothy Day and her colleagues to war, William Cavanaugh has also analysed how the theological concept of the body of Christ was operative in Day’s thinking and living. Cavanaugh contrasts Day’s understanding of the concept with that of Pope Pius XII.

In the October 1934 issue of The Catholic Worker, Dorothy Day wrote an article entitled ‘The Body of Christ’. It began with a rhetorical question from St Clement of Rome: ‘Why do the members of Christ tear one another, why do we rise up against our own body in such madness; have we forgotten that we are all members of one another?’ The article went on to describe war as an illness that affects the whole body.[14] She also quoted St Cyprian, saying that war was ‘the rending of the Mystical Body of Christ’. Pope Pius XII also employed the concept of the body of Christ in his comments about World War II. However, in sharp contrast to Dorothy’s writings, the pope emphasised how the unity of brothers in Christ persisted even though they fought in opposing armies:

Though a long and deadly war has pitilessly broken the bond of brotherly union between nations, We have seen Our children in Christ, in whatever part of the world they happened to be, one in will and affection, lift up their hearts to the common Father, who […] is guiding the barque of the Catholic Church in the teeth of a raging tempest. This is a testimony to the wonderful union existing among Christians.[15]

For Pius XII, the unity of Christians seemed to be something that floated above the violent events of this world. Making a strong distinction between the political and spiritual spheres of life gave him sufficient wiggle room to maintain universal spiritual authority while not calling into question the political loyalty of individual Christians to their nation states. Cavanaugh concludes that: ‘The practical effect of such distinctions was to allow the possibility of being a good Catholic and a good Nazi at the same time.’[16] It should also be acknowledged that the real political goal of Pope Pius XII’s theology was not to condone Nazism but to allow the papacy to remain sufficiently politically neutral so as to serve as a peace broker between the warring nations.

By contrast, Dorothy Day employed the doctrine of the mystical body of Christ in ways that showed how completely inimical it was to war. For Dorothy, being a member of the body of Christ meant that participation in a war with other members, or possible members, of Christ’s body was simply inconceivable.[17] She did not permit a segregation of the spiritual and other spheres of life. Nor could she fathom how people could be somehow ‘mystically’ united while they were physically trying to kill each other. She therefore also refused to acknowledge a separate hegemony of the nation state to which individuals could be obedient even if Christ’s authority and call demanded otherwise.[18] According to Cavanaugh, for Dorothy Day: ‘The Mystical Body does not hover above the national borders which divide us; it dissolves them.’[19]

Cavanaugh acclaims Dorothy Day’s construal of the mystical body of Christ as a return to the early Church’s understanding of the doctrine. In his study, Corpus Mysticum, Henri de Lubac showed how in the early Church the term ‘mystical body’ did not refer primarily to the Church but to the Eucharistic elements, while the term corpus verum, ‘real body’, was used to refer to the Church.[20] De Lubac’s study shows how these meanings were inverted in the Middle Ages: the Church being identified as the corpus mysticum, the Eucharist as the corpus verum. One of the consequences of this shift in meaning was that the ‘mystical’ life of the Church came to be associated with hidden spiritual lives of individuals rather than with the real historical communion that the Eucharist brought about in the community of believers.[21]

The re-emergence of pacifism and a dual tradition

For the first half of the twentieth century, just war theory was the mainstream Catholic position regarding issues of war and peace.[22] While popes and bishops sometimes spoke out against war, pacifist convictions were not fostered and there were no doctrinal proscriptions against participation in war. McNeal interprets Pope Benedict XV’s exhortations for peace during the First World War as displays of pastoral concern without speaking of ‘the fundamental issue of the rightness or wrongness of war’.[23] Furthermore, Pius XII’s theology of the body of Christ, as analysed by Cavanaugh, enabled nation states to exploit the Church’s unwillingness to intervene directly in international political matters. The documents of the Second Vatican Council and pronouncements of successive contemporary papacies, however, have re-established pacifism as an authentic Catholic position. Ashley Beck suggests that this was partly motivated by the twentieth century’s mounting death toll, the result of two world wars, bloody revolutions and continued colonial violence.[24] The dropping of two atomic bombs may also have exhausted the Church’s tolerance to violence. Pope Pius XII condemned it in the strongest possible language, calling it ‘an infernal massacre’ and an ‘outrage against civilization’.[25]

The council fathers recognised in Gaudium et spes that rapid developments in modern warfare required them to ‘undertake an evaluation of war with an entirely new attitude’.[26] This new attitude resulted in the condemnation of acts of war that resulted in the destruction of whole cities, i.e., the atom bomb. It also vindicated the Catholic Worker’s philosophy of active non-violence with the following statement, which, to all intents and purposes, could have come from the pen of Dorothy Day herself:

It seems right that laws make humane provisions for the case of those who for reasons of conscience refuse to bear arms, provided however, that they agree to serve the human community in some other way.[27]

After the council, the statements of the popes continued to stress the importance of non-violent means. Writing about the historic events of 1989, Pope John Paul II celebrated the fact that the Cold War had been resolved without resorting to another war, but by ‘the nonviolent commitment of people who, while always refusing to yield to the force of power, succeeded time after time in finding effective ways of bearing witness to the truth.’[28] The documents of the council and magisterial papal teachings now clearly include positions based on both just war theory and the principle of active non-violence: a dual tradition has been brought back into balance.

Conclusion

In truth, the emergence of evangelical pacifism in the twentieth century would be better described as a re-emergence or a recovery. The pacifist tradition had been a part of the Catholic tradition from its earliest days but it had become a silent partner to the just war tradition. Thanks to Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement, pacifism and its deep theological roots were recovered and, through their writing and public speaking, taken ‘to the streets on picket lines and in jail and to the common man and woman.’[29] They tuned into a movement of the Holy Spirit that gathered momentum as time progressed, and which was ultimately confirmed by the teaching office of the Church.

Niall Leahy SJ is a member of the Irish Jesuit province and is a priest at Gardiner Street parish, Dublin.

[1] Editorial, The Catholic Worker (January 1942), 2.

[2] Arthur Sheehan, Peter Maurin (Garden City, NY: Hanover House, 1959), pp. 50-51. Cited in Mark and Louise Zwick, The Catholic Worker Movement: Intellectual and Spiritual Origins (New York: Paulist Press, 2005), p. 251.

[3] Patricia McNeal, ‘Conscientious Objection during World War II’, The Catholic Historical Review 61, no. 2 (April 1975): 222-242, 223.

[4] Cited in McNeal, ‘Conscientious Objection’, 227.

[5] Cited in Zwick, The Catholic Worker Movement, p. 255.

[6] Cited in Zwick, The Catholic Worker Movement, p. 250.

[7] Zwick, The Catholic Worker Movement, p. 253.

[8] McNeal, ‘Conscientious Objection’, 253.

[9] Zwick, The Catholic Worker Movement, p. 259

[10] Zwick, The Catholic Worker Movement, p. 262.

[11] Zwick, The Catholic Worker Movement, p. 263

[12] Zwick, The Catholic Worker Movement, p. 201.

[13] Cited by Zwick, The Catholic Worker Movement, p. 235.

[14] Cited in Zwick, The Catholic Worker Movement, p. 252.

[15] William T. Cavanaugh, ‘Dorothy Day and the Mystical Body of Christ in the Second World War’ in Dorothy Day and the Catholic Movement: Centenary Essays, ed. William J. Thorn, Phillip M. Runkel, and Susan Moutin (Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press, 2001), p. 459.

[16] Cavanaugh, ‘Mystical Body’, p. 460.

[17] Cavanaugh, ‘Mystical Body’, p. 461.

[18] Cavanaugh, ‘Mystical Body’, p. 461

[19] Cavanaugh, ‘Mystical Body’, p. 457.

[20] Cavanaugh, ‘Mystical Body’, p. 464.

[21] Cavanaugh, ‘Mystical Body’, p. 464.

[22] McNeal, ‘Conscientious Objection’, 223.

[23] McNeal, ‘Conscientious Objection’, 223.

[24] Ashley Beck, ‘How Catholic Teaching about War Has Changed: The Issues in View’, New Blackfriars 96, no. 1062 (March 2015) : 130-146, 133.

[25] Cited in Beck, ‘Catholic Teaching’, 138.

[26] Gaudium et spes (1965) §80.

[27] Gaudium et spes, §79.

[28] Pope John Paul II, Centesimus annus (1991), §23

[29] Stephen T. Krupa SJ, ‘Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement: Centenary Essays’ in Dorothy Day and the Catholic Movement: Centenary Essays, p. 194.