During the Jubilee Year of Mercy, which begins on 8 December, we are encouraged by Pope Francis to reflect on the ‘concrete reality’ of God’s mercy. Teresa White FCJ ponders the ways in which we can recognise and practise merciful behaviour in our lives, and encourages us to be attentive to expressions of mercy throughout this year, particularly during its Advent beginning.

There are some words – and I do not think they are over-numerous – which belong to the vocabulary of the sacred. They include serenity, joy and generosity. Patience and faithfulness would be among them too, as would peace. Most of these words are readily understood and are in common usage in secular vocabulary, too, but I think it true to say that even in the rough and tumble of human discourse they always have a special significance. When we say them, hear them, read them, they seem to draw us into the realm of the spiritual, into the domain of God. Such words are in the truest sense poetic in that they communicate even before they are analysed; indeed they lift human communication to a new level, they nudge us to contemplate eternal realities.

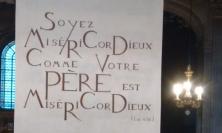

Mercy is another of these words and since the election of Pope Francis it has become particularly associated with him. In the document introducing the Jubilee Year of Mercy, Misericordiae Vultus (the two opening words, which give the bull its name, translate as ‘the face of mercy’), Francis describes mercy as, ‘the bridge that connects God and man, opening our hearts to a hope of being loved forever despite our sinfulness’ (MV §2). Mercy – sometimes thought of as the wisdom of God, attentive to our need for love in spite of our flaws and our mistakes, our sins and our crimes – addresses us from that place ‘beyond’ and resonates with all that is good and beautiful in relationships, in life, in existence. Mercy is God’s tenderness living in us.

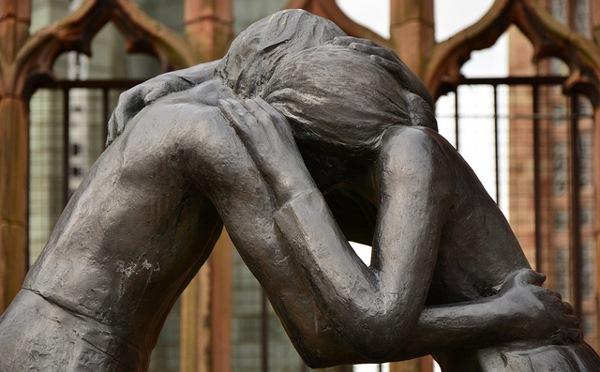

Although it is a biblical concept par excellence, mercy is not to be found among the traditional list of the virtues, perhaps because, in a sense, it encompasses them all. The Latin word is misericordia, and its etymology carries the twofold connotation of wretchedness (miseria) and love (symbolised in heart, cor). Mercy is love responding to misery; it is misery calling forth love. An attribute of God, mercy is compassion and love shown towards those who have no claim to expect or receive kindness. When we see it, witness it, experience it, we are left in no doubt: mercy is grace, and it shines out in the merciful. Such people, when wronged, do not hold on to injuries and grievances. For those of us who have ever regretted our heartlessness, our unwillingness to overlook injuries that others have inflicted, George Eliot, in a memorable line from Adam Bede, captures the deeply ambivalent juxtaposition of mercy and justice: ‘It is never our tenderness that we repent of, but our severity’, and this is true even when, in the light of cold logic, our severity seems merited.

Pope Francis holds that, ‘the mercy of God is not an abstract idea, but a concrete reality’ (MV §6). This was movingly demonstrated, for example, in September this year, when nine worshippers were killed inside a church in Charleston, South Carolina, and representatives of the victims’ families at once came forward to deliver a message of forgiveness. One relative said: ‘I forgive you and ask God to have mercy on your soul… You hurt a lot of people, but I forgive you.’ Another example of this same desire for leniency, not severity, for mercy, not retribution, is recounted in a moving reflection by Fr Matt Malone SJ in America magazine: A firefighter was called out during the night to a serious road accident and found the car to be irreparably damaged, but the driver, apart from minor cuts and bruises, virtually unscathed. The firefighter quickly realised, however, that the front-seat passenger was fatally injured – and that it was his own son. The firefighter and the victim were Fr Malone’s father and brother, respectively. The driver, who had been drinking, was charged in connection with the accident and at the trial a victim’s statement was read by Fr Malone’s father on behalf of the family. He requested that the court impose the minimum sentence possible on the young driver, who, he said, had to live with the knowledge of what he had done – a burden ‘far greater than any punishment [the] court could dispense’. That family, in their merciful response to this tragedy, were able to retain their peace and serenity in the midst of their sorrow.

The feast of the Immaculate Conception of Mary on 8 December is the day chosen by Pope Francis for the opening of the Jubilee Year of Mercy. As always, this feast falls during Advent, and as I reflected on the concept of mercy and what it means, I thought how appropriate it was that the Jubilee should begin at this moment in the Church’s year. The famous words spoken by Portia in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice came to my mind unbidden:

The quality of mercy is not strain’d,

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

Upon the place beneath. It is twice blest:

It blesseth him that gives and him that takes.

These lines poetically describe the essence of mercy, its very soul, but they also wonderfully encapsulate the spirit and atmosphere of the liturgical season of Advent. They recall – even, almost, translate – the refrain of the ancient anthem, Rorate Caeli. Inspired by the Vulgate version of Isaiah 45:8, the words, in English, run: ‘Drop down dew, ye heavens, from above/ and let the clouds rain down justice’. Portia suggests that mercy, the ‘gentle rain from heaven’, softens and irrigates ‘the place beneath’, thus freeing justice from the ‘strain’, the strict judgmental severity, which can hinder fruitfulness. Mercy mitigates the compulsions of law – it is voluntary; it drops gently, like heaven’s rain, a natural and gracious quality rather than a legal one. Further on, Portia continues, ‘… we do pray for mercy;/ And that same prayer doth teach us all to render/ The deeds of mercy’. When in sincerity and truth we recognise our own need for mercy, we know we need to be merciful to others in our turn.

In Misericordiae Vultus, Pope Francis reminds us that the abundant mercy of God, made visible in Jesus Christ, has the power to revitalise us: ‘Mercy is the force that reawakens us to new life and instils in us the courage to look to the future with hope’ (MV, §10). His deep desire is that during the forthcoming Jubilee Year, that message may reach all people: ‘In our parishes, communities, associations and movements, in a word, wherever there are Christians, everyone should find an oasis of mercy’ (MV, §12). Amen to that!

Sister Teresa White belongs to the Faithful Companions of Jesus. A former teacher, she spent many years in the ministry of spirituality at Katherine House, a retreat and conference centre run by her congregation in Salford.