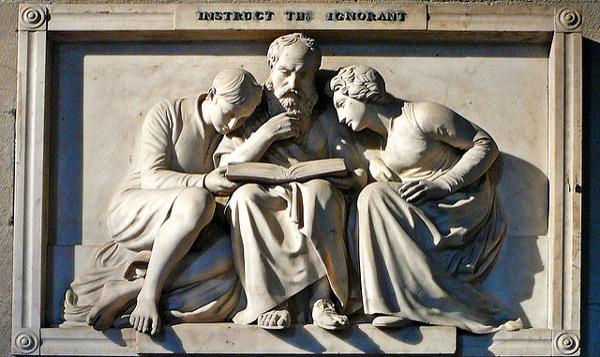

In this Jubilee Year of Mercy, Pope Francis has called for Lent to be ‘lived more intensely as a privileged moment to celebrate and experience God’s mercy.’[1] Thinking Faith will respond to this invitation by offering a series of reflections on the Seven Spiritual Works of Mercy in the context of Laudato si’. We begin by asking what it means to ‘instruct the ignorant’.

‘Ignorant’ is not a word with which most of us would like to be associated. At best, it denotes a lack of knowledge, in general or in relation to a particular subject; but nowadays it tends to be used more often as a synonym for what the Oxford English Dictionary lists as its informal meaning: ‘discourteous’.

In order for us to think about what the Spiritual Work of Mercy of ‘instructing the ignorant’ involves, then, we need to think carefully about who ‘the ignorant’ are. We are not being asked to give a lesson in manners to those we consider to be rude, as the common usage of the word might imply. Rather, we are being asked to emulate Philip who, when he encountered the eunuch who confessed that he did not understand the words of the prophet Isaiah – saying, ‘How can I, unless someone guides me?’ – ‘proclaimed to him the good news about Jesus.’[2]

To instruct the ignorant, then, is to proclaim the gospel to those who have not heard it, to lead people closer to God by imparting knowledge to them that they do not yet have. The recipient of this instruction might be someone who is taking the first steps in faith – a child, or someone who has never encountered Christ. Or it might be someone who is on a different journey – someone seeking a truth they haven’t quite found, someone who has rejected what they have they have understood of God’s love, or perhaps even someone whose zeal has led them away from the heart of the gospel. In any case, we can think of it as an attempt to bring faith and reason into right relationship with one another so that the fullness of life might be experienced. Pope John Paul II does not use the word ‘ignorance’ in his encyclical Fides et Ratio, but in a sense he cuts to the heart of what this work of mercy is trying to achieve when he highlights why faith and reason need one another:

It is an illusion to think that faith, tied to weak reasoning, might be more penetrating; on the contrary, faith then runs the grave risk of withering into myth or superstition. By the same token, reason which is unrelated to an adult faith is not prompted to turn its gaze to the newness and radicality of being.[3]

This work understandably has a strong association with parents and teachers, who are tasked with passing on the faith to the next generation; but each of us is called to undertake all of the works of mercy. So how can all of us, including those of us without professional or parental duties to educate, instruct the ignorant?

We turn to Laudato si’. In fact Pope Francis uses the word ‘ignorance’ only once, to say that: ‘the fragmentation of knowledge and the isolation of bits of information can actually become a form of ignorance, unless they are integrated into a broader vision of reality.’[4] That is to say that in the care of our common home, with which the encyclical is concerned, nothing can be fully known, let alone any solutions to the problems facing our planet achieved, without an awareness of the interconnectedness of everything. This is a theme to which the pope returns repeatedly. He does not dismiss the importance of scientific learning and technological developments in order to meet the challenges that our world is facing, but these are only parts of a wider solution. Even as he admits that there are those who will dismiss the idea of a Creator, he still emphasises that this wider solution requires a dialogue between science and religion,[5] and so he goes on to share ‘The Wisdom of Biblical Accounts’. Here is an implicit call for people of faith to witness to the conviction that is expressed in those accounts, ‘that everything is interconnected, and that genuine care for our own lives and our relationships with nature is inseparable from fraternity, justice and faithfulness to others.’[6] Demonstrating this care, and bringing such insights into discussions about the dangers facing our planet, especially when our interlocutors do not recognise the need for joined-up thinking, is an important way in which this work of mercy can be practised.

In contrast to his one reference to ‘ignorance’, Pope Francis focuses explicitly on the ‘instruction’ side of this work through an entire chapter on education, in which he further develops the call to a richer vision of reality, one which goes beyond scientific limits. But his aim in this chapter is not to give a classroom education in the science of global warming, nor to give a checklist of ways to reduce our carbon footprints or shop ethically – although these of course have their place. The chapter is titled ‘Ecological Education and Spirituality’,[7] and in it the pope writes that: ‘Our efforts at education will be inadequate and ineffectual unless we strive to promote a new way of thinking about human beings, life, society and our relationship with nature.’[8] In other words: all the scientific, economic and political solutions in the world will not help our planet and its people unless we realise why they matter. And as he says subsequently, and elsewhere, the ‘light offered by faith’ is uniquely placed to illuminate these relationships: ‘The rich heritage of Christian spirituality, the fruit of twenty centuries of personal and communal experience, has a precious contribution to make to the renewal of humanity.’[9] Being beacons of this light is a way in which we can instruct those who are ignorant of the richness of the faith.

This suggestion that we can instruct through means other than our words is important. The strong association with teaching points towards a corporal dimension to this work, so we might need to dig a little deeper to find what cements it in the list of spiritual works. James Keenan SJ offers a helpful observation: ‘While the beneficiary of the corporal works is the recipient, it is the reverse among the spiritual works. Often the beneficiary is the one who practices the spiritual works.’[10]

The biblical text which is often cited as a grounding for this work is the final two verses of Matthew’s Gospel, in which Jesus commands his disciples to ‘make disciples of all nations... teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you.’[11] Matthew does not make this the conclusion of his gospel for stylistic reasons, because it has a dramatic flourish; rather, waiting until the very end of his story to include this instruction makes it very clear that until this point, the disciples were not ready to undertake this role. They had to go through their own learning experience in order to be qualified to teach others. That this commission comes so late in the day emphasises that it is ‘a formidable task, because this gospel is loaded with the teaching of Jesus’.[12]

In any field, to be in a position to instruct others means that one has received instruction oneself, which is clearly a great benefit; but not all learners become teachers, so this prior learning is not necessarily a benefit of performing the instruction. However, inherent in the act of instructing in faith is a further benefit, one which cannot be decoupled from the act. In order to instruct, one must understand, and in the case of the gospel, one cannot truly understand it without living it: anyone who teaches the faith has to ‘walk the talk’.[13] And this is not a burden, this is a blessing. For your thoughts and actions to be permeated by the good news of Christ is, unequivocally, a benefit, and anyone who performs this work of mercy aims to share that benefit with others.

So yes, it is a spiritual work, but instructing the ignorant in the context of Laudato si’ does in fact have a very concrete goal: ‘an awareness of the gravity of today’s cultural and ecological crisis must be translated into new habits.’[14] As we reflect on and practise the works of mercy during the season of transformation that is Lent, we might find encouragement to instruct the ignorant in the words of Leo Buscaglia: ‘Change is the result of all true learning.’

Frances Murphy is Editor of Thinking Faith.

[1] Pope Francis, Misericordiae Vultus (2015), §17.

[2] Acts 8:30-35

[3] Pope John Paull II, Fides et Ratio(1998), §48.

[4] Pope Francis, Laudato si’ (2015), §138.

[5] Ibid., §62

[6] Ibid., §70

[7] Ibid., Chapter 6 (emphasis added).

[8] Ibid., §215

[9] Ibid., §216

[10] James F. Keenan SJ, The Works of Mercy (Rowman & Littlefield, 2005), p.61.

[11] Matthew 28:19-20.

[12] Peter Edmonds SJ, ‘Matthew: A saint for today’, Thinking Faith (22 September 2009).

[13] Nicholas King SJ, ‘The Values of Catholic Education’, Thinking Faith (6 September 2013).

[14] Laudato si’, §209