What do the 53 Jesuit saints, whom we remember on 5 November, have in common, other than their membership of the Society of Jesus? ‘The list of Jesuit saints parallels the diversity of the Society itself’, writes Jesuit historian Thomas Flowers, as he considers how the Society has been a crucible in which Jesuit saints have been able to live lives of remarkable holiness.

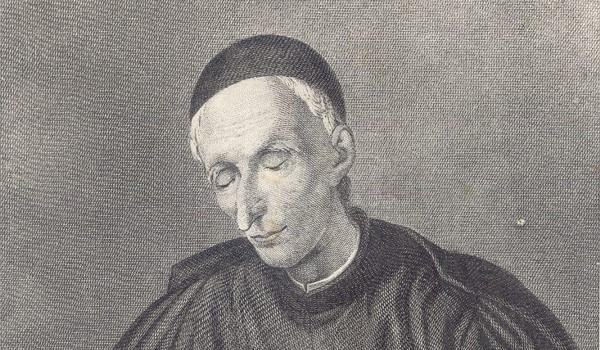

In the Corsican Bay of Bastía in 1767, on one of the ships over-crowded with the exiled Spanish members of the Society of Jesus, a letter reached St Joseph Pignatelli SJ from his brother. His brother offered Fr Pignatelli a way out of the mess in which being a Jesuit had landed him when the King had ordered the expulsion of all Jesuits from his realm. If he would renounce his membership in the Society, his brother assured him, his family could make certain he would be welcomed back into Spain and find a comfortable position as a priest. Fr Pignatelli responded: ‘I have no intention of abandoning my present state. On the contrary, it is my firm determination to live and die a Jesuit.’[1] He would live to see the Society suppressed and would die before its universal restoration. But through a quirk of the confused ecclesiastical politics that accompanied the Society’s suppression and restoration, Fr Pignatelli did, indeed, die as a Jesuit, having reentered the Society years later through the Russian remnant of the Society which had never been fully suppressed.

Joseph Pignatelli is one of the 53 canonised saints of the Society of Jesus. His reputation for holiness depends, more than anything else, upon his loyalty to the Society and his Jesuit brethren in the face, first, of the Jesuit exile from Spain and, then, of the universal suppression of the Society by Pope Clement XIV in 1773. That a stalwart member of a religious order that one pope suppressed could be named a canonised saint by another pope is remarkable.[2] But Pignatelli never regarded his loyalty to the Society as detrimental to his loyalty to the pope, and he never wavered in his devotion to the Church. This is, in many ways, what makes for a Jesuit saint: devotion to the Church expressed through devotion to the Society of Jesus. The Society did not serve, for Jesuit saints, as a refuge from the problems of the Church or the world – the Society was the best way they knew how to serve the Church that they loved.

Given the Society’s longstanding diversity of ministries, any more precise profile of a Jesuit saint would make little sense. From the beginning, Jesuits never did just one thing. A brief glance at the original ten Jesuits named in the papal bull that confirmed the foundation of the Society in 1540 reveals, among others: St Francis Xavier, the missionary to India and Japan; Diego Laínez, the renowned theologian at the Council of Trent; Nicolás Bobadilla, who reformed countless monasteries and served as the first Jesuit military chaplain; St Pierre Favre, who lived his brief Jesuit life travelling about preaching, hearing confessions and giving the Spiritual Exercises; and Simão Rodrigues, who served as both a provincial superior and a confidant and spiritual advisor at the Portuguese royal court. The Society did not have a predominate ministry in its earliest days, and even when the decades passed and the Society became more and more associated with the myriad schools it founded and ran, nevertheless, beyond the ranks of school teachers and administrators, there were always Jesuit missionaries, confessors, preachers, chaplains and theologians, not to mention scientists, writers, doorkeepers and cooks.

What defines Jesuits as Jesuits depends less on what they do and much more on how they do it – what the Society has long referred to as ‘our way of proceeding’. The ubiquity of the phrase in the Society’s internal documents is only rivalled by the diverse definitions for it provided by Jesuits and historians alike. Yet what remains clear in the various, and sometimes contradictory, meanings attributed to the phrase is that it intends to describe the characteristic style of the Jesuits in the varied ministries in which Jesuits engage. Thus, it is a phrase rooted in Jesuit spirituality – in the way Jesuits learn to pray, discern and act contemplatively from their earliest experiences of making the Spiritual Exercises. Its use at the beginning of the Jesuit Constitutions offers a particularly revealing glimpse of its implications: here, Ignatius explains that Jesuits ‘should always be ready, in accord with our profession and way of proceeding, to roam in every part of the world whenever it is enjoined to us by the Supreme Pontiff or our immediate superior.’[3] It is ‘in accord with’ the Jesuit way of proceeding that Jesuits need to be ready to go anywhere, and to do anything the pope ask them to do. At the heart of the Jesuit way of proceeding lies Jesuit availability to serve the Church wherever the need is greatest.

This is why Jesuit saints appear in such motley array. From missionary martyrs like Ss John de Brébeuf, Roque Gonzalez and John de Brito (martyred in North America, South America and India, respectively), to St Alphonsus Rodrigues, the Jesuit brother who was doorkeeper at the Jesuit college in Majorca, to St Robert Bellarmine who was a controversial theologian and eventually a cardinal, the list of Jesuit saints parallels the diversity of the Society itself. There are great teachers and founders of schools like St Peter Canisius, pastors and confessors like St José Maria Rubio, and even the famous trio of Jesuit saints who died during their formation: St Stanislaus Kostka, who died as a novice; St John Berchmans, who died while studying philosophy; and St Aloysius Gonzaga, who died while studying theology. Not only does no single ministry unite these Jesuit saints, but they are similarly unlike one another in temperament and personality. They range from the appealing humility of St Alphonsus Rodrigues, who wrote that, ‘in dealing with Jesus and Mary I go along with holy fear as I speak with them, and they answer me with gentle sweetness and teach me’, to the startling zeal of John de Brébeuf, who promised the Lord to ‘bind myself in this way so that for the rest of my life I will have neither permission nor freedom to refuse opportunities of dying and shedding my blood for you.’[4]

If such diverse Jesuits garnered their reputations for sanctity in such varied ways and settings, then the question arises as to what bearing their being Jesuits had on their becoming saints. The answer leads us away from the stories told of their heroic exploits and virtue, and toward the quiet of their interior lives. St Stanislaus Kostka died before his eighteenth birthday at the Jesuit novitiate of Sant’Andrea in Rome. The building where Kostka lived for his brief time in the Society has been demolished, but in the present community that has since been built nearby, there exists a shrine to Kostka in the form of a replica of his room, which contains several features salvaged from the original. Just outside the door that leads into the room laden with an enormous baroque marble statue of Kostka in repose on his death bed, a letter has been affixed to the wall that is sometimes described in pious words as ‘a letter from a saint to a saint about a saint.’ This epitaph is technically accurate, for the letter was written in 1567 by St Peter Canisius to St Francis Borgia and one point in the letter describes Canisius’s impressions of St Stanislaus Kostka. Canisius, then provincial of the Superior Germany Province, explains to Borgia, then superior general of the Society, that Stanislaus had been unable to enter the Society in his native Poland because of his family’s opposition, and so had fled with the intention of entering the Society in Rome. Canisius assured Borgia that Stanislaus had already ‘showed himself ever faithful to his duties and constant in his vocation,’ and so ‘we hope for great things from him.’[5]

Beyond the marble statue of Stanislaus and the pious reverence given to this missive for its association with three different holy men, the story speaks eloquently of what it means to be a Jesuit saint. Canisius and Borgia were companions in the Society of Jesus, and although Borgia was by that time the superior general, Canisius had entered the Society before him. Their relationship, even in their letters, was one marked by warmth and mutual esteem. Canisius was constantly asking for Borgia’s prayers, and in the preserved diary of Borgia on 5 February 1568 Borgia notes, ‘prayers said for that matter of Canisius.’[6] These two companions, who devoted a considerable portion of their lives as Jesuits to the governance and care of the Society itself, saw Stanislaus’s determination to be a Jesuit and recognised him as one whose zeal would serve the Society well. Their mutual commitment to aid him in entering the Society despite his family’s opposition was both rooted in their concern for his welfare and their hopes for what he would bring to the Society’s mission. In the end, this preserved moment of encounter in the lives of these three Jesuit saints points to the centrality of their identity as Jesuits in the way they approached their service to the Church and the world. It was confidence like Borgia and Canisius had in each other and the sort of hope they both had in Stanislaus that allowed all three the freedom to live lives of remarkable holiness.

There is, in the end, only one way that all the canonised saints of the Society of Jesus became saints: by serving the Church according to the Society’s particular way of proceeding. The Society taught these Jesuits how to be available to serve the Church as the Church needed. And the Society gave them the care they needed to serve well. Undoubtedly, the Society sometimes fails to live up to these standards: sometimes Jesuits are not cared for by their superiors as well as they need to be, and sometimes Jesuits are not as free to serve the Church as they ought to be. The foibles of the Society and its failures in serving the Church are well known. But what the canonised saints among the Society’s membership represent is the Society at its best. They represent a Society that is not tied to one particular sort of ministry, but is instead available for whatever ministry for which the moment calls. They demonstrate the care the Society’s leadership takes in cultivating and forming vocations, and the mutual support Jesuits give to one another. And they underline that Jesuit holiness is always conceived of in service to the Church. St Joseph Pignatelli would not abandon his Jesuit vocation in order to save himself from the consequences of the suppression of the Society. But neither did he ever dream of ceasing to serve the Church as a priest. He could only understand his priestly vocation in the context of his Jesuit formation. But he would not let the Church’s suspicion of the Society keep him from being a faithful servant of the Church as a priest. There was no contradiction for him, as there was no contradiction for any other Jesuit saint: they found their way to holiness by serving the Church as Jesuits.

Thomas Flowers SJ recently completed a PhD in Jesuit history at the University of York and is currently teaching Jesuit history to Jesuits in formation in the USA.

[1] As quoted in D. A. Hanly, Blessed Joseph Pignatelli: A Great Leader in a Great Crisis (New York: Benziger Brothers, 1937), pp.78-79.

[2] Joseph Pignatelli was declared a saint by Pope Pius XII in 1954.

[3] Jesuit Constitutions §92. My translation is from the original Latin in: Monumenta Historica Societatis Iesu, Sancti Ignatii De Loyola: Constitutions Societatis Iesu vol. 3, General Examen, Ch. 4, 26.

[4] As quoted in the Supplement to the Divine Office for the Society of Jesus (St. Louis: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 2002), 90, and The Liturgy of the Hours, vol. IV (New York: Catholic Book Publishers, 1975), 1503.

[5] As quoted in James Brodrick, Saint Peter Canisius (London: Sheed & Ward, 1935), p.675.

[6] As quoted in Brodrick, Saint Peter Canisius, p.686.