Concluding Thinking Faith’s series on George Tyrrell, Joe Egerton suggests that we should see Tyrrell’s story as a tragic episode in the history of the interplay between faith and reason – one that resulted from an approach to philosophy radically different to that taken by Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

George Tyrrell’s excommunication resulted from his disagreement with a philosophical analysis set out in the 1907 encyclical, Pascendi Dominici Gregis. It is an illustration of the terrible consequences for good individuals when we fail to find a solution to the problem that confronts a philosophical religion – that of reconciling faith and reason. John Paul II’s Fides et Ratio sets out a charter for philosophy as an aid to understanding the faith, based on the pre-suppositions made by St Thomas Aquinas for all philosophising. This charter underpins the present Pope’s response to the challenge of reconciling faith and reason: his call to the West to overcome its aversion to engaging with the questions that underlie our rationality.

The problem of a philosophical religion

It would be a large error to regard Catholic Christianity’s philosophical dimension as a product of the middle ages. In his lecture on Faith, Reason and the University,[1] Pope Benedict XVI spoke of ‘the intrinsic necessity of a rapprochement between Biblical faith and Greek inquiry’.[2] On the Pope’s account, Christianity has always been heavily influenced by Hellenism, that is to say it has always had strong philosophical content. So, the Pope argues, even in the early Church ‘the fundamental decisions made about the relationship between faith and the use of human reason are part of the faith itself; they are developments consonant with the nature of faith itself.’

The philosophical content of Western Christianity was made explicit by St Augustine of Hippo (born 354AD, converted 386, died 430). He developed and articulated the concept of the will, found in St Paul, drawing on Platonic philosophy and providing an account of the Fall in which humans became unable to reason towards good – a defect from which they were saved by the Incarnation. The legacy of Augustine was an intrinsically philosophical religion.[3]

If a religion incorporates beliefs about the nature of human beings and human reason, then it becomes possible to apply the terms heterodox, erroneous and heretical to philosophical propositions (e.g. ‘it is impossible to have knowledge of God’s nature’).[4] The Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 asserted that there is between God’s creator spirit and our created reason a certain analogy [5] and thus made the proposition that humans can have, by analogy, a very restricted knowledge of God a matter of Catholic orthodoxy. It is this that Kant denied, and over his denial that George Tyrrell tripped.

The positive and negative aspects of a close relationship between theology and philosophy can be illustrated by two examples. First, St Anselm (1033-1109) offered a philosophical proof of the existence of God, known as the ontological argument. This is in the form of a prayer. Conversely, we have the condemnation in 1141 of Peter Abelard (1079-1142). His exploration of logic was intended to forge a better understanding of the Holy Trinity, but his opinions were denounced by St Bernard of Clairvaux.[6] This is a prototype for George Tyrrell’s treatment.

A thirteenth century dispute over Aristotle

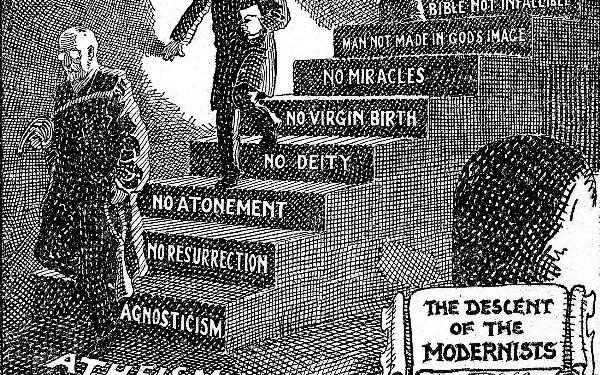

There is an interesting parallel to be drawn between the nineteenth century response to Kant and the thirteenth century response to Aristotle. We may note that the central philosophical allegation against ‘the modernists’ was that they had displaced Aristotle with Kant; in the thirteenth century, it was those who displaced Plato with Aristotle, thus radically changing Augustinian Christianity, who were subject to Episcopal condemnation.

In the 13th century, Aristotle’s major treatises, which had been all but forgotten in the West but had been studied in the Arab world, were recovered together with commentaries by Averroes (Ibn Rushd) and Maimonides (Rabbi Moses ben Maimon). This raised great difficulties in the Christian West. Some of Aristotle’s teachings – for example, on the eternity of the world – were at odds with dogma. Worse, Aristotle’s philosophy, being radically at odds with St Augustine’s Platonism, called into question the entire relationship between theology and other disciplines.[7]

The conflict between Augustinian theology and Aristotelian philosophy was to lead to the greatest development in Western thought since Aristotle himself: St Thomas Aquinas’s synthesis of these conflicting views in numerous works, culminating in the Summa Theologiae. But the initial response to the publication of Aristotle’s works was to prohibit them, as happened in 1210 in Paris.[8]

The prohibition lapsed, but the incorporation of Aristotle into Christian thought remained controversial: St Bonaventure condemned Aristotelianism in his Eastertide lectures in 1273, and in 1277, three years after the death of Aquinas, Stephen Tempier, Bishop of Paris, condemned twenty propositions advanced by him. In 1289, the Franciscan Order prohibited the copying of the Summa without the incorporation of a text by William de la Mare condemning 117 of its propositions.[9]

We have in these events an example of the complications that may arise for a religion in which ‘fundamental decisions made about the relationship between faith and the use of human reason are part of the faith itself’.

The Blessed Antonio Rosmini

There is a widespread but erroneous belief that from the 1270s St Thomas Aquinas dictated Catholic thinking. There have been long periods – the early sixteenth century when Ignatius, Francis Xavier and Peter Favre studied St Thomas in Paris being an exception – when he was preserved only by the Dominicans and Papal interest. The dominant Catholic thinkers of the early nineteenth century – especially Antonio Rosmini (1797-1855) – were heavily indebted to Kantian ideas; Thomists were a disruptive minority. As late as 1865 a Jesuit Provincial described a statement of the Thomist position as ‘a condemnation of the whole body of the Society and, what is worse, the Episcopate.’[10] Rosmini’s theological project was to re-work earlier statements of Catholic belief so as to make it comprehensible and acceptable to a world in which ‘reason’ no longer meant ‘the system of Aristotle’.

By the 1850s, a revival of Thomism was well under way, and as Thomism became increasingly accepted, Rosmini became the target of criticism, and some of his works were put on the Index.[11] Rosmini was not accused of having false philosophical views; rather he was accused of theological error, specifically pantheism. Rosmini, like Abelard, loyally accepted the condemnation, but protested at his treatment and this led Pius IX to order an examination of Rosmini’s works. The Vatican removed them from the Index in 1854.

Pius IX’s successor, Gioacchino Pecci, who became Pope Leo XIII in 1878, had become a Thomist under the influence of the Jesuit Rector of the Roman College, Luigi Taparelli d’Azeglio. In the twenty years after Rosmini’s death, Thomism became the dominant force, and in 1887 Leo approved a fresh condemnation of a number of Rosmini’s propositions. There had in the meantime been the First Vatican Council. The third session had agreed decrees covering faith and reason, and these had re-affirmed the Church’s claim to adjudicate on matters of science when a proposition of faith was involved: ‘Hence all faithful Christians are forbidden to defend as the legitimate conclusions of science those opinions which are known to be contrary to the doctrine of faith, particularly if they have been condemned by the church; and furthermore they are absolutely bound to hold them to be errors which wear the deceptive appearance of truth.’

This story has a happy ending: over a hundred years later, John Paul II publicly praised Rosmini, and in 2001, he confirmed a note signed by Cardinal Ratzinger that ‘superseded’ – that is revoked – the posthumous condemnation.[12] Rosmini was beatified in 2007. This episode does, however, further illustrate the inherent problems of a faith that contains propositions about human reason.

Aeterni Patris and the changing understanding of St Thomas Aquinas

In August 1879, Leo XIII issued an encyclical letter ‘on the restoration of Christian philosophy’, Aeterni Patris. This encyclical is the charter document from which modern studies of St Thomas derive. Leo XIII praised St Thomas and urged that he be given precedence but prefaced this with the statement: ‘every word of wisdom is useful’; so the value of philosophising in general is recognised.[13] Aeterni Patris follows Vatican I in stressing the importance of faith, but it asserts that faith and science work together in a positive way and expressly warns against treating every bit of scholastic philosophy as true: ‘if there be anything that ill agrees with the discoveries of a later age, or, in a word, improbable in whatever way – it does not enter our mind to propose that for imitation to our age.’

Aeterni Patris was drafted by Josef Kleutgen, a Jesuit philosopher of remarkable ingenuity. Kleutgen argued that there had been a rupture in the history of philosophy. On this he was right, as he was in concluding that Descartes and his successors could not be treated as carrying on the work of Plato, Aristotle and Aquinas. However, he also argued that Aquinas had developed epistemological arguments that offered superior answers to those provided by Descartes and Kant. The representation of Thomas Aquinas as engaged in the development of an epistemology arose from Kleutgen’s use of Francisco Suarez to elucidate St Thomas. Suarez (whom Kleutgen placed before the rupture) is a distinctively modern philosopher, often regarded as having a better claim than Descartes to be the father of modern philosophy.[14]

Aeterni Patris had both bitter and sweet fruit. The sweet fruit was the establishment of centres devoted to the study of St Thomas, resulting in a depth of understanding lacking in Kleutgen and his contemporaries. Marechal, Rousselot and Maritain all developed distinctive contributions, and Marechal in turn influenced Karl Rahner. Pope John Paul II praised these and other developments in Catholic philosophy.[15] It is an interesting question as to whether they represent a reconciliation of elements of Kant’s thinking with Catholic orthodoxy, or the development of epistemologies that, drawing on Kant and so being accessible to modernity, are refutations of some of his central beliefs.

The bitter fruit of Aeterni Patris was that, by the reign of Pope St Pius X[16], it had become possible to condemn those who tried to explain Christian beliefs using modern – and specifically Kantian – philosophical vocabulary.

The early twentieth century: the rise of intolerance

The 1907 encyclical, Pascendi Dominici Gregis condemned the thought of the modernists, including George Tyrrell, who sought to incorporate the ideas of modern philosophy into discussions about and defences of faith.[17] However, it was not just a theoretical analysis of modernism; it called for action. Equating ‘modernism’ with pride, it urged bishops to dismiss young priests who were found to be ‘proud men’ (40). It included a list of measures that bishops were to take – including setting up ‘watch committees’ (55) – and concluded with a requirement to make a triennial report to Rome (56) ‘lest what we have laid down thus far should fall into oblivion’.

Pascendi was followed in September 1910 by a motu proprio, Sacrorum antistitum. [18] This contained an oath to be sworn by all Catholic priests upon their ordination to the subdiaconate. In June 1914, Pope Pius X issued a further motu proprio, Doctoris Angelici,[19] criticising those who had failed to adhere to his order to teach the theology of St Thomas Aquinas.

The heresy hunt in the Church now reached the highest levels. In a letter to Pius X in summer 1914, Secretary of State Cardinal Merry del Val[20] accused the Archbishop of Bologna (a few months earlier made a Cardinal) of modernism. Pius X died on 20August 1914 and the Cardinal Archbishop of Bologna was elected as Benedict XV on 3 September: the Papal study was unlocked, the new Pope sat at his predecessor’s desk and his eyes lighted on the letter of denunciation; Merry del Val was summarily dismissed as Secretary of State and spent the rest of his life merely as Archpriest of St Peter’s. The influence of heretic hunters declined somewhat. Nevertheless, the oath promulgated in Sacrorum antistitum was re-affirmed by the Holy Office in March 1920 and on 29 June 1923, Pope Pius XI re-affirmed Doctoris Angelici in his encyclical Studiorum Ducem.[21] The oath was eventually removed by Paul VI in 1967.

And this still left unfinished business. With propositions about reason integral to the faith, error and heterodoxy remain possibilities. John Paul II and the present Pope have set out a way forward.

John Paul II and Benedict XVI: Rational enquiry recognised as a good

In September 1998, Pope John Paul II issued the encyclical Fides et Ratio. He stated that the Church did not have one particular philosophy and condemned the claim that a single system could represent the totality of philosophy as philosophicalpride. Pascendi, Sacrorum Antistitum, Doctoris Angelici and Studiorum Ducem were not mentioned. The role of the Magisterium, he said, is to insist that philosophy is studied.[22]

Faith, Reason and the University opens with the present Pope celebrating the lively inter-disciplinary exchange[23] he had enjoyed as a young professor at the University of Bonn and concludes with a call to the West to have the courage to examine the basis of its rationality – to recognise the breadth of human reason. On Kant and the others condemned in Pascendi, he had this to say:

A critique of modern reason from within has nothing to do with putting the clock back to the time before the Enlightenment and rejecting the insights of the modern age. The positive aspects of modernity are to be acknowledged unreservedly: we are all grateful for the marvellous possibilities that it has opened up for mankind and for the progress in humanity that has been granted to us.[24]

The message of both popes is unambiguous: rational enquiry is a good, and that extends to the enquiries of the great modern philosophers.

However, this should not be interpreted to be rejecting St Thomas or promoting a ‘free for all’. Fides et Ratio asserts that there is ‘an Implicit Philosophy’ with four elements: (a) the principles of non-contradiction, finality and causality, (b) the concept of the person as a free and intelligent subject, with (c) the capacity to know God, truth and goodness and (d) ‘certain fundamental moral norms which are shared by all.’[25]

Discussing Fides et Ratio, Ralph McInerny observed that the components of the Implicit Philosophy leap from the pages of St Thomas, and adds:

The principles of Implicit Philosophy are presupposed by Thomas Aquinas as he begins formal philosophizing; indeed the former is regulative of the latter. Since these starting points or principles of Thomism are in the common domain, Thomism is not a system of philosophy, if a system is defined in terms of peculiar and distinguishing principles.[26]

p>

This raises the problem of reconciling elements of the philosophical systems which Fides et Ratio praises with the Implicit Philosophy. McInerny’s solution?‘The new and the old in philosophy are not compatible if one of them denies the principles of Implicit Philosophy; they are compatible, the one enlarging the other, if both respect the principles of Implicit Philosophy.’ Fides et Ratio is thus a charter for rational enquiry in a framework of faith. We are back to the real approach of Thomas Aquinas.

Conclusion

Some would prefer that we do not mention the condemnations of Thomas Aquinas, Antonio Rosmini and George Tyrrell. But that would be a denial of the courage required to respond to the repeated call of the Holy Spirit to rise to ‘the challenge of thinking the faith…that each generation has to make its own and always remains an unfinished project’[27]. No one recognised that the project is always unfinished more than St Thomas, and it is this St Thomas that St Ignatius urges us to study in his rules for thinking with the Church.[28]

Joe Egerton has worked in financial regulation since 1985 and ran a course on Aristotle with a little help from Aquinas for the Mount Street Jesuit Centre.

[1] Faith, Reason and the University is the lecture given at a meeting with representatives of Science in theAula Magna of Regensburg University, 12 September 2006 during the Pope’s visit to Germany. The lecture achieved widespread publicity owing to a single phrase from an exchange between the Byzantine Emperor Manuel II and an Islamic scholar used by the Pope as a theme for the lecture. The Pope’s main concern is to argue that God is bound to truth and justice and to deny that God can command evil.

[2]The relevant section of the Pope’s text reads:

Modifying the first verse of the Book of Genesis, the first verse of the whole Bible, John began the prologue of his Gospel with the words: "In the beginning was the λόγος". This is the very word used by the emperor: God acts, σὺν λόγω, with logos. Logos means both reason and word - a reason which is creative and capable of self-communication, precisely as reason. John thus spoke the final word on the biblical concept of God, and in this word all the often toilsome and tortuous threads of biblical faith find their culmination and synthesis. In the beginning was the logos, and the logos is God, says the Evangelist. The encounter between the Biblical message and Greek thought did not happen by chance. The vision of Saint Paul, who saw the roads to Asia barred and in a dream saw a Macedonian man plead with him: "Come over to Macedonia and help us!" (cf. Acts 16:6-10) - this vision can be interpreted as a "distillation" of the intrinsic necessity of a rapprochement between Biblical faith and Greek inquiry.

Note: the Pope also observed that the creation of the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures) imported Hellenistic concepts into Judaeism: thus making Judaeism a philosophical religion before Christianity.

[3] Hugh of St Victor (c1097 -1141) wrote a book, the Didascalon, that describes the Augustinian structure of theology and philosophy as it had evolved.

[4] We should always remember that an opinion can be in error and heterodox without its holder being a heretic; a heretic is one who persistently repeats or teaches an erroneous opinion. This was codified by Trent but was generally held throughout the Middle Ages – e.g. Meister Eckhart admitted to being in error but denied being a heretic.

[5] The concept of understanding God by way of analogy was put like this by St Bonaventure:

All created things of the sensible world lead the mind of the contemplator and wise man to eternal God... They are the shades, the resonances, the pictures of that efficient, exemplifying, and ordering art; they are the tracks, simulacra, and spectacles; they are divinely given signs set before us for the purpose of seeing God. They are exemplifications set before our still unrefined and sense-oriented minds, so that by the sensible things which they see they might be transferred to the intelligible which they cannot see, as if by signs to the signified (Itinerarium mentis ad Deum, 2.11)

[6] The initial trial was heard at Sens, the seat of the Primate of France; the case was transferred to Rome where St Bernard obtained a condemnation but Peter died on his way to make representations in person.

[7] For details and a discussion, see Alasdair MacIntyre’s Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry (the 1988 Gifford lectures) The three versions are The Ninth Edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, Nietzsche’s Zur Genealogie der Moral and Aeterni Patris.

[8] It is probable that the works of Averroes were also prohibited. A factor in this was the use by the Cathars (the Albigensian heretics) of some of Aristotle’s arguments.

[9] The official title of the book was the Correctorium Fratris Thomae – younger Dominicans referred to it as the Corruptorium

[10] Alasadir MacIntyre Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry page 72; quoting Paolo Dezza Alle origini del neotomismo Milano, 1960, page 60.

[11] That is to say, Catholics were forbidden to read them under pain of mortal sin – the Index was ‘Index librorum prohibitorum’ – the list of forbidden books. In 1929, Cardinal Merry del Val wrote a foreword that identified the leader of a campaign of malicious publications as the devil himself.

[12]On 1 July, 2001, the Congregation for the Doctine of the Faith issued a NOTE on the Force of the Doctrinal Decrees Concerning the Thought and Work of Fr. Antonio Rosmini Serbati. The Note was signed by Cardinal Ratzinger and confirmed by Pope John Paul II. Its decision reads as follows:

The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, following an in-depth examination of the two doctrinal Decrees, promulgated in the 19th century, and taking into account the results emerging from historiography and from the scientific and theoretical research of the last ten years has reached the following conclusion: The motives for doctrinal and prudential concern and difficulty that determined the promulgation of the Decree Post obitum [issued by the Holy Office and confirmed by Pope Leo XIII on 14 Dec, 1887] with the condemnation of the "40 Propositions" taken from the works of Anthony Rosmini can now be considered superseded. This is so because the meaning of the propositions, as understood and condemned by the Decree, does not belong to the authentic position of Rosmini, but to conclusions that may possibly have been drawn from the reading of his works.

Unsurprisingly, this note too has excited criticism from those who regard both popes as heterodox – see, for instance, James Larson: Rosmini’s Rehabilitation and the Ratzinger Agendain Christian Order, February 2004. There is a helpful discussion of the philosophical differences between Rosmini and his critics in Macintyre’s Three Rival Versions. Hedevotes several pages to Rosmini, arguing on page 71 (writing before the CDF note) that ‘insofar they [sc. Rosmini’s central theses about the human mind] are interpreted so as to secure his theological orthodoxy, they render his philosophical position incoherent.’ The context of all of this is the philosophy of Kant.

[13] See Paragraph 31:

While, therefore, We hold that every word of wisdom, every useful thing by whomsoever discovered or planned, ought to be received with a willing and grateful mind, We exhort you, venerable brethren, in all earnestness to restore the golden wisdom of St. Thomas, and to spread it far and wide for the defence and beauty of the Catholic faith, for the good of society, and for the advantage of all the sciences. The wisdom of St. Thomas, We say; for if anything is taken up with too great subtlety by the Scholastic doctors, or too carelessly stated-if there be anything that ill agrees with the discoveries of a later age, or, in a word, improbable in whatever way-it does not enter Our mind to propose that for imitation to Our age.

[14] Descartes was taught at La Fleche by Jesuits under the influence of Suarez.

[15]Examples given by John Paul II in his encyclical Fides et Ratio:

[a] Some devised syntheses that stood comparison with "the great systems of idealism." [b] Others established the epistemological foundations for a "new consideration of faith in the light of a renewed understanding of moral consciousness." [c] Others started with an analysis of immanence and "opened the way to the transcendent." [d] Finally, some "sought to combine the demands of faith "with the perspective of phenomenological method."

[16] George Tyrrell regarded Pius X as ‘a good man’. Among the most joyful events in the life of most parishes are the First Communion Masses – few now realise that but for the vigour of Pius X children would be denied the Eucharist. Quam Singulari (‘The pages of the Gospel show clearly how special was that love for children which Christ showed while He was on earth’)is an example of Papal determination in a rather different cause from Pascendi.

[17] See previous articles in Thinking Faith’s series on George Tyrrell: http://www.thinkingfaith.org/articles/20090706_1.htm; http://www.thinkingfaith.org/articles/20090714_1.htm; http://www.thinkingfaith.org/articles/20090724_1.htm

[20] Merry del Val was a more than slightly controversial figure – as the New York Times commented in article that refers to George Tyrrell

[22] Fides et Ratio, 61:

If it has been necessary from time to time to intervene on this question, to reiterate the value of the Angelic Doctor's insights and insist on the study of his thought, this has been because the Magisterium's directives have not always been followed with the readiness one would wish. In the years after the Second Vatican Council, many Catholic faculties were in some ways impoverished by a diminished sense of the importance of the study not just of Scholastic philosophy but more generally of the study of philosophy itself. I cannot fail to note with surprise and displeasure that this lack of interest in the study of philosophy is shared by not a few theologians.

[23]with historians, philosophers, philologists, and between the two theological faculties (Protestant and Catholic)

[24] This is the Regensburg lecture – that caused a sensation because the Pope quoted Manuel II. The lecture deserves careful reading and reflection.

[25] The relevant section reads in full:

Although times change and knowledge increases, it is possible to discern a core of philosophical insight within the history of thought as a whole. Consider, for example, the principles of non-contradiction, finality and causality, as well as the concept of the person as a free and intelligent subject, with the capacity to know God, truth and goodness. Consider as well certain fundamental moral norms which are shared by all. These are among the indications that, beyond different schools of thought, there exists a body of knowledge which may be judged a kind of spiritual heritage of humanity. It is as if we had come upon an implicit philosophy, as a result of which all feel that they possess these principles, albeit in a general and unreflective way.

[27] Tony Carroll SJ, ‘Modernism: The Philosophical Foundations’, Thinking Faith, http://www.thinkingfaith.org/articles/20090724_1.htm

[28] The Thomas Aquinas that St Ignatius encountered when he studied the Summa at Paris – when he shared a room with Peter Favre, the greatest expert in Aristotle of his time – cannot have been the St Thomas that is characterised in Pascendi. The St Thomas of Pascendi could only have been conjured up by somebody who had read Suarez – and Suarez was eight and a half years old when Ignatius died in 1556. The St Thomas that Ignatius encountered, the St Thomas that he commended in the Rules for Thinking with the Church, was the philosopher-craftsman whose approach clearly was: 1. Pray for God’s guidance; 2. Look at the best arguments for and the best arguments against any position; 3. Then make up your mind. How does St Ignatius tell us to make a difficult choice? One way is to look at the arguments for and against and to reflect and pray over them. And always to start any meditation by asking God for a good outcome.

Thinking Faith’s series on George Tyrrell SJ:

![]() George Tyrrell and Catholic Modernism – Oliver Rafferty SJ

George Tyrrell and Catholic Modernism – Oliver Rafferty SJ![]() George Tyrrell and John Sullivan: Sinner and Saint? – Michael Hurley SJ

George Tyrrell and John Sullivan: Sinner and Saint? – Michael Hurley SJ![]() Modernism: The Philosophical Foundations – Anthony Carroll SJ

Modernism: The Philosophical Foundations – Anthony Carroll SJ