The ‘Prayer for Generosity’ is much-loved by followers of Ignatian spirituality, although little is known about its authorship. The prayer is attributed frequently to St Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits, but was it really composed by him? Jack Mahoney SJ investigates the origins of this ‘brief but elegant prayer’.

When I was about ten years old and my elder brother was about fifteen, he went on a school retreat to Craighead House, the Jesuit spirituality centre which existed then near Bothwell in Scotland, and came back enthusiastic about a prayer for generosity which had figured in the retreat. He could not remember it all, so he wrote to the Jesuit priest who had given the retreat and asked for a copy of the prayer, which duly arrived. This was a brave thing for a young Scots lad to do; and no doubt my brother’s devotion to the prayer contributed to his decision a few years later to study for the diocesan priesthood and then to spend fifty years of his life in generous priestly ministry.

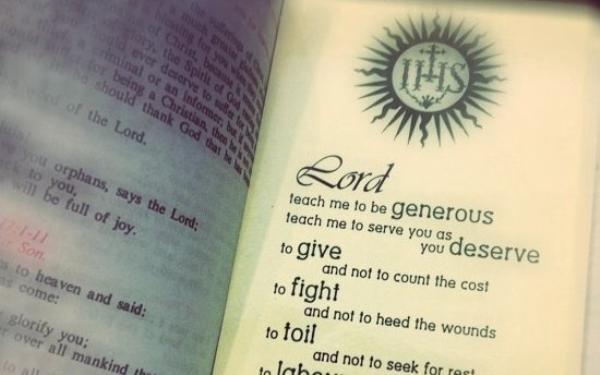

The prayer which must have helped mould my brother’s priestly vocation and life was, of course, the one beginning, ‘Lord, teach me to be generous’:

Lord, teach me to be generous,

to serve you as you deserve,

to give and not to count the cost,

to fight and not to heed the wounds,

to toil and not to seek for rest,

to labour and not to look for any reward,

save that of knowing that I do your holy will.

It is the most famous prayer connected with Saint Ignatius Loyola, founder of the Jesuit Order, and one with which all British Jesuits are totally familiar. Yet it is one which for years has also puzzled me, because we know almost nothing about it. The other famous Ignatian prayer, ‘Take, O Lord, and receive’ was composed by Ignatius as part of his Spiritual Exercises, but there appears to be no well-known source for the prayer for generosity. In fact, I have seen it described cautiously a couple of times in prayer anthologies as ‘attributed to St Ignatius.’

The brief but elegant prayer that we have is notable in several ways. Studying its composition, one comes to realise that it is almost entirely made up of one-syllable words, a remarkable stylistic feature which, even unconsciously, gives the prayer a powerful compactness. This is an effect easy to produce in English, which is no longer an inflected language utilising different word-endings. Moreover, the ten-fold repetition of infinitives in the prayer creates a regular rhythmic effect, like waves; and so also does the pattern shown in lines 3-6, stressing a and not b, c and not d, e and not f, g and not h.

As far as the prayer’s content is concerned, occasional minor additions can be found, such as an initial address of, ‘Dear Lord’, or ‘Dearest Lord’, or an ending with the words ‘that I do your holy will, my Lord and King.’ Its aspirations are expressed simply, modestly and discreetly, rather than ostentatiously or emotionally, spelling out what generosity involves in real practice. This low key approach may strengthen the prayer’s being considered Ignatian, as also does its being a prayer for total generosity. I once had it misquoted to me as including the clause ‘to fight and not to feel the wounds’, but I corrected this firmly as ‘to fight and not to heed the wounds’.

In style and content, the prayer for generosity seems to read as if it were written originally in English. But its actual provenance is unknown. I have tried from time to time to trace its origin and source, without any success. It does not appear to figure anywhere in the writings of Ignatius, and I have been unable to find it, or any reference to it, in any version of the Spiritual Exercises or in any commentary on them, far less in any biography of Ignatius. I began to wonder, in fact, whether it might have been composed originally in English, possibly by one of the Anglican scholars who took up Ignatian studies and the Spiritual Exercises in the nineteenth century. I found no evidence for any of this, yet it is difficult to think of any original version which could be so simple, yet so polished, in another European language.

Recently, I asked the Oxford-based Ignatian scholar, Fr Joseph Munitiz SJ, for any light he might be able to throw on the prayer, and he drew my attention to an article that he had written some years previously in the privately-circulated quarterly of the British Jesuits, Letters and Notices. [1] This showed how Fr Munitiz had himself once done some personal research on the prayer and had come to the conclusion that it is ‘pseudo-Ignatian’, not a genuine Ignatian prayer at all. He did, however, have some positive information to offer on the prayer, directing the reader to a Spanish annotated bibliography of St Ignatius’s writings which was composed by Ignacio Iparraguirre, in which the prayer figures briefly.[2] In his study, Iparraguirre notes that the ‘prayer to Jesus Christ. . . has been quite often in modern times attributed to St Ignatius’, and he adds that ‘the oldest attribution we have found is in Xavier de Franciosi, La dévotion à saint Ignace (Montreuil-sur-Mer, imprimerie Notre Dame des Prés, 1897).’

Ipparaguirre further comments that ‘the ideas of this prayer are those of St Ignatius, but not its style.’ Denying an Ignatian origin, he adds that ‘we have not been able to discover the author,’ and continues, ‘P. Franciosi gives the following [French] text which is, with slight variations, the one which has become widespread today.

O Verbe de Dieu bien-aimé,

Apprenez-moi à être généreux,

à vous servir comme vous méritez d’être servi

à donner sans compter

à combattre sans souci des blessures

à travailler sans repos,

à me dépenser sans attendre d’autre récompense

que celle de savoir que je fais votre sainte volonté. Ainsi soit-il.

Franciosi’s pamphlet is subtitled, ‘Meditations, Prayers and Practices in Honour of the Founder of the Society of Jesus’ and prints the ‘Prayer of St Ignatius to Our Lord Jesus Christ’ between a blessing of Ignatius on water for the sick and an ‘Offering of all Our Being to God’, the latter identified as from the Spiritual Exercises.[3] Fr Munitiz followed up Iparraguirre’s reference to de Franciosi, to examine the latter’s other writings and possible sources in the hope of securing further information on the prayer, but he found nothing to add.[4] He did, however, unearth further denial of the Ignatian authorship of the prayer, in a Dutch work on Jesuit prayer which reproduces the prayer in Dutch and states that no Spanish or Latin original has been found, reporting that it occurs ‘among other places’ in the book by de Franciosi, ‘who unjustifiably attributes it to St Ignatius’.[5]

In his article, Fr Munitiz reported that the highly regarded Jesuit spiritual guide, the late Fr Michael Ivens, had denied an Ignatian source for the prayer and suggested that it was probably composed by a French Jesuit, ‘somebody he thought had been involved in youth work (perhaps the French Scout movement) in the 20th century’.[6] My first reaction to this news was to consider it somewhat unlikely, but later a friend of the Editor informed us that the prayer was composed by a French Jesuit, one Fr Jacques Sevin SJ, about 1910, adding that it is to be found in French prayer-books as ‘the scouts’ prayer’, and that Père Sevin had visited Lord Baden-Powell to discuss with him founding the Scout movement in France.

The indispensable Wikipedia provides an informative French biography of this distinguished French Jesuit whose cause for beatification is now in progress.[7] He is credited with founding the French Catholic Scout movement about 1920 after first meeting Baden Powell in 1913 at an Alexandra Palace rally. As part of diffusing his views on Scouting in France he wrote an official handbook and set various prayers to music, including – behold – ‘a prayer attributed to St Ignatius Loyola, which became “the scout prayer”.’

The prayer/hymn for generosity as printed in the Wikipedia article differs slightly from the version given by de Franciosi: it begins with ‘Lord Jesus’, is set in the plural, ‘Lord, teach us to be generous. . .’, which would fit in well with a prayer for Scouts to recite or sing together, and has a few other minor differences. Among the many musical compositions he produced for his French Scouts, I was charmed to find that Père Sevin included a French translation of the famous Scottish song, Auld Lang Syne. Reading of this suddenly recalled for me, and made sense of, a memory of a sunny morning in Switzerland way back in 1948, where I was a Scottish representative at a European scouting jamboree, including fellow-Scouts I got to know from France. As we were all packing up our tents, the familiar notes of my national Scottish farewell came from the loudspeakers ranged around the camp site! It was evidently known to other nationalities.

It would be wonderful if Sevin’s collective prayer for his Scouts had been translated by him from an English original into French – after all, he did translate Auld Lang Syne into French! – but the fact is that the French version we have from Sevin is later than the de Franciosi version which dates, according to Iparraguirre, from 1897, long before Sevin met Baden Powell. Moreover, Père Sevin’s collective version to be sung by groups of Scouts is obviously an adaptation of an earlier French version, such as we have from de Franciosi, and sadly has nothing to tell us about the origin of the prayer.

We are still, therefore, left with several questions. One, which may not be so outlandish as it sounds, is whether the prayer was first written in English and later translated into French by de Franciosi to include in his book on devotion to St Ignatius. However, a comparison of the English and French versions that we have cannot establish which may have priority, and even though the English version is stylistically superior this could not prove it is the original. What is still unknown is the identity of the brilliant stylist who either composed the English version or crafted its translation from its original tongue into English.

Finally, if our prayer to Christ for total generosity is shown to be not by Ignatius, does it still remain Ignatian? We saw Iparraguirre judge that the ideas are of St Ignatius, even if the style is not. Fr Munitiz, however, does not agree, commenting that ‘a hall-mark of Ignatian prayer is that it wells up from a realization of one’s own worthlessness coupled to a wonder at God’s gracious goodness’, whereas the prayer for generosity emphasises the contribution the person praying wants to offer, putting the person at the centre, rather than Christ and the love of God. It ‘lacks the depth and richness of a genuine Ignatian prayer’. [8]

I find these remarks unconvincing. The prayer is far from being self-centred: it is entirely based on asking the Lord to teach one to be generous and outgoing in His service, culminating in being completely subservient to the Lord’s ‘holy will’. In taking this form, it expresses the regular stress on personal activity found in Ignatian theology which is continually in tension with being receptive to God’s initiative. After all, Ignatius’s main work for perfecting souls is to instruct them how to perform spiritual exercises! And his continual prayer in the meditations in the Exercises is for the individual to be made and to feel different. Moreover, in the Contemplation to obtain love, the first thing Ignatius enjoins the exercitant to bear in mind is that ‘love should consist more in deeds than in words’,[9] and this is shown typically in the preparatory prayer which introduces all the Exercises and bids us to ‘ask our Lord God for the grace to direct my thoughts, activities and deeds to the service and praise of is Divine Majesty”His Divine Majesty’.[10] In fact, this preparatory prayer which runs as a constant refrain throughout the Exercises is remarkably similar in tone to the prayer for the grace of generous self-giving that we have been considering.

I suggest that, while we should conclude that the prayer for generosity is apparently not the work of St Ignatius himself, one thing of which we can be sure is that the master of generosity would wholeheartedly approve of it.

Fr Jack Mahoney SJ is a regular contributor to Thinking Faith. His latest book is Christianity in Evolution: An Exploration (Georgetown University Press, 2011)

[1] Fr J. Munitiz, SJ, A Pseudo-Ignatian Prayer, Letters and Notices, vol. 97, no. 426 (Autumn 2004), 12-14.

[2] I. Iparraguirre, Orientaciones Bibliograficas sobre San Ignacio de Loyola [Subsidia ad Historiam S.I., number 1], Rome 1965, ed. 2, p. 136, no. 523.

[3] Xavier de Franciosi, S.I., La dévotion à saint Ignace, Méditations, Prières et Pratiques en honneur du Fondateur de la Compagnie de Jésus, 2nd ed., Montreuil-sur-Mer, imprimerie Notre Dame des Prés, 1897, p. 79.

[4] Munitiz, 13-14.

[5] Societas Jesu Orans, Anon, Nijmegen 1941; Quoted in Munitiz, 14.

[6] Munitiz, 12.

[7] http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacques_Sevin.

[8] Munitiz, 14.

[9] Ignatius, Spiritual Exercises, no 230.

[10] Ignatius, Spiritual Exercises, no 46.