‘St Ignatius of Loyola was first and foremost a man of God who in his life put God, his greatest glory and his greatest service, first … he left his followers a precious spiritual legacy that must not be lost or forgotten.’ These words of Pope Benedict XVI in 2006 describe the founder of the Society of Jesus, whose feast we celebrate on 31 July. But just what is this legacy? We invited ten friends of Thinking Faith to tell us who Ignatius is to them.

John Dardis SJ

President of the Conference of European Provincials of the Society of Jesus

Just after I was appointed Provincial of the Society of Jesus in Ireland in 2004, I went to pray at the tomb of St. Ignatius at the Gesù in Rome. I needed reassurance; I felt daunted by the challenge of leading a province and was very aware of my own frailty. I had always looked up to Ignatius as someone ‘other’, ‘different’. But as I prayed in the Gesù, I realised that he too was somebody with weaknesses and limitations, in spite of which he gave leadership and vision. I prayed that, just as Ignatius in his day managed to lead the Society forward, I too, in some small way and despite my limitations, might contribute to the mission of the Society in Ireland.

The second aspect of Ignatius that I find attractive is the way he gathered companions around him in Paris – Francis Xavier, Peter Favre and others. He was able to identify their potential and help them to find God in a passionate way. They became strong apostles throughout Europe. That is the Ignatius of pastoral friendship, of deep spirituality, of warmth and of challenge.

There is a third Ignatius, the one who was able to take risks. He sent Francis Xavier to the Far East without knowing exactly what that entailed. He opened new missions and ministries. He risked a totally new form of religious life. He could do this because serving Christ was primary and everything else worked for that.

Finally, there is Ignatius the ascetic, the man who could renounce so much for the mission. I think of those long years he spent in Rome writing the Constitutions which became the bedrock of the Society. This Ignatius is a consolation whenever I feel overwhelmed with e-mails and yet more reports.

Ignatius the leader; Ignatius the pastoral companion; Ignatius the risk-taker; Ignatius the ascetic. Ignatius is all of this and more.

Roger Dawson SJ

Editor of Thinking Faith

When I was an undergraduate at Durham University, I was asking lots of questions about my faith and in some tentative sense wanted to deepen it, so I asked my University Chaplain about spiritual direction. I think I wanted him to be my spiritual director, but he wisely put me in touch with a religious sister in Durham from an Ignatian congregation. At our first meeting, in a room with one of the finest views in Europe above the River Wear overlooking Durham Cathedral and the castle, she told me about Ignatian spirituality, about ‘finding God in all things’: that we are given gifts by God, and we need to discover these, develop them to the full and place them at God’s service; that the world was created good; and that there is great goodness to be found in the world, along with the bad stuff. This was so different from my (largely mistaken) reading of other types of spirituality that seemed to me to be world-denying and self-denying, and not much fun.

And she told me about St Ignatius of Loyola: how he was a soldier ‘with a past’, a swashbuckling braggart who had been arrested for brawling, who was inspiring and impetuous in equal measure. She told me about the Battle of Pamplona and how a French artilleryman's cannonball changed Ignatius’s life (and by extension many others, including later on my own); of his long convalescence and conversion; and of his nascent gift for discerning the spirits in his own experience, in which he was convinced that God was at work. I was captivated. I had left the British Army less than two years earlier having served in an infantry regiment and I remember thinking, ‘I know people like this’. And I can remember thinking to myself that this is the sort of man with whom I would like to spend an evening in the pub. I had not met then the ‘scary Ignatius’ whom we Jesuits love, revere and fear, but even when I did, that did not put me off. What always came through to me was this passionate, big-hearted man with a great capacity for friendship who went round Europe engaging people in conversation and inspiring them to be something different, something more. It was a while before I was hit by my own version of the cannonball, but in the meantime I started to meet Jesuits with big hearts and a capacity for friendship and conversation who inspired me too.

Joe Egerton

Chief Operating Officer of a stockbroker

My mother often spoke with admiration of a friend, Fr Wilson-Browne, who was a Jesuit missionary in Guyana. I later came to know a number of Jesuits at Stonyhurst, some of whom have become close friends. But in the sixties one learned of St Ignatius himself through cloying hagiographies. It was only in the 1990s – my fifties – that, following the restoration of the methods of Jerome Nadal, Ignatius’s great lieutenant, I really discovered the Spiritual Exercises and the Autobiography. Nadal’s great contribution to the early Society was as messenger for Ignatius, introducing the Constitutions, creating a shared culture that went beyond a collective experience of the exercises and emphasising an inclinatio ad praxim. For anyone who works in the world – especially in that Temple of Mammon, the City of London – this emphasis is crucial if one’s religious belief is not to be separated from most of one’s life.

Nadal is the early Jesuit with whom I empathise most. He was not one of the companions for whom Peter Favre celebrated Mass on the Feast of the Assumption in 1534. He came to Ignatius later, and with the baggage of an advanced degree. My Ignatius is, like his, mediated by the head. This creates a barrier with those whose experience is more directly with the heart. And, like Nadal, I fear Ignatius. We can be relieved that Christ is to be our judge, and we can think of saints that are forgiving and understanding. St Ignatius is not one of those. When asking myself, ‘What would Ignatius make of this?’, the answer is often uncomfortable. But it is constructively uncomfortable: for alongside a demand for the highest standards comes practical help in finding the Lord, something that in dark days, when all seems to be going wrong, is a refuge and way back to hope.

Stefan Garcia

By the River Cardoner in the Catalan town of Manresa, Ignatius experienced a truth which so overwhelmed him that he said all of the things he would learn in every other vision put together never equalled that one moment of awareness. Reading about this experience in a seedy attic bedroom in my student let, I recognised instantly in the description a moment shared.

One feels sheepish about describing one’s visions; you are free to use whatever tools you wish to decipher mine. Walking home from Mass on a spring morning, as I reached the wood before the Downs on my university campus, I was possessed with a vision of great light. The birdsong amplified inside me into a message definitely expressed but as impossible to repeat as visions are. The radioactive glow of love filled me and floated around me. I started running down the hillside, singing and dancing for the joy of this knowledge always taught but never so fully felt. The perfect moment of that day seemed like a treasure of enormous wealth, a hundred talents that I would give away over the course of a lifetime. I knew after reading about Ignatius’s experience that I should share his path of companionship with Christ. I saw my vision reflected in the waters of the Cardoner and felt drawn to the man who saw it before me. This was the dream for me. A million visions have come and gone, but this one remains. Through it all, Ignatius affirms, ‘Remember the vision.’

Michael Holman SJ

Principal of Heythrop College, University of London

Each 31 July during his 24 years as Superior General of the Society of Jesus, Fr Peter-Hans Kolvenbach would celebrate Mass in honour of St Ignatius Loyola in the Gesù Church, the principal Jesuit Church in Rome.

In his homilies on these occasions, as in his annual letters, Fr Kolvenbach reflected on aspects of our Jesuit or Ignatian identity, some of which we might be inclined to overlook. In this he did us Jesuits a real service. There is always the danger that we pick and choose, and so shape Ignatius in our own image such that he loses his creative power in our lives. The homily I have been reading and re-reading of late is entitled ‘St Ignatius and his Passion for the Church’. Let me see if I can paraphrase it.

Fr Kolvenbach says that Ignatius incarnated the Gospel invitation to lose one’s life in order to find true life forever in Jesus. When Ignatius wrote about the Church he never failed to see in her Jesus’ spouse, united to him, in her all too human reality, in the mystery of love.

So in handing over his whole life to the Church, Ignatius gave himself to Christ. For this reason, he renounced his own projects and ideas and placed himself at the service of the Church. Similarly, he did not want the Society he founded to work for its own progress and well-being but to commit itself exclusively to the projects and missions of the Church.

Ignatius’s dedication to the Church, says Fr Kolvenbach, had a painful aspect. Those who love the Church tend to dream of an ideal Church. But Ignatius had his eyes open to the reality of the Church of his time, much in need of reform, and it was with this Church that he identified. He did not stand alongside it, or outside it; nor did he adopt an attitude of subtle criticism or of sharp, negative attacks. Rather, he set about the work of reform, beginning with himself and those whom the Lord put across his path.

For Ignatius, following Jesus meant losing one’s life for a Church which here and there was disfigured or rejected. He had learnt from his Lord. Fr Kolvenbach concludes that there was no other way for the Church, composed of saints and sinners, the strong and the weak, to follow Christ than, with him, to choose the way of the Cross. To refuse to suffer for or because of the Church would be nothing other than to retreat before the Cross.

At a time when the Church is criticised and said to be in crisis, I have found it helpful to reflect on these wise words from a very wise man.

Austen Ivereigh

Catholic commentator and writer, co-ordinator of Catholic Voices

There are two kinds of hard work, and Ignatius taught me the difference. To use a sailing metaphor, the first is like beating into the wind, against the tide: almost anything you try to do, however simple – make a cup of tea, adjust the sails, navigate – demands great effort: it is a slog. The other is like sailing with the wind behind you, following the tide; there are the same tasks, and the work remains hard, but the major effort is not yours. The tasks are fulfilling, not draining. When we find our direction, which is God’s will for us, it is much plainer sailing.

Ignatius, who was a man of action, learned that the most effective work happens when we allow God to act through us; and that means, sometimes, letting go of the reins and not trying to control the outcome. I love the stories involving Ignatius learning to do that – like when he let the donkey decide whether he should avenge an insult – because it so obviously goes against his nature as soldier and a nobleman. And that is what makes Ignatius the convert so endearing: he is a modern man learning to renounce his autonomy for the sake of a greater freedom. It is the struggle of our time, and of each of us stuffed with know-how and can-do.

Ignatius’s discernment rules are sophisticated, but they are really those of Gamaliel in Acts 5. We can strain our wills and our muscles to defeat what is of God (or to pursue what is not of God), but it is like beating into the wind; whereas what is of God will lift us up and carry us forward, like the wind and tide behind us.

Ignatius and his followers in the Society of Jesus taught me that a long time ago, but I have only begun, finally, to live it. The Catholic Voices project which now takes up much of my life is not the result of any real effort on my part; I waited, as Ignatius taught me, for the wind to catch the sails, and since then I have been navigating the best I can a course which I know is not mine to determine. It is hard work, like anything worthwhile; and not always plain sailing. But it is seldom a slog, and almost always deeply satisfying.

Thomas M. McCoog SJ

Archivist of the British Province of the Society of Jesus

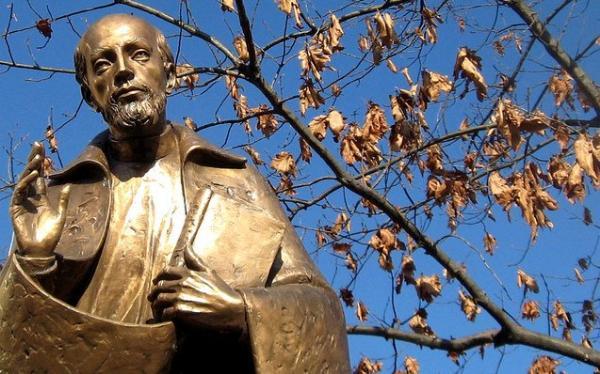

In 1971 at the Jesuit novitiate I encountered for the first time Ignatius the Pilgrim, a quasi-Don Quixote who travelled to the beat of Godspell. Subsequent historical research revealed a variety of Ignatiuses: the armed counter-reformation destroyer of heresies; the tearful priest in a Roman chasuble at Mass; a simple cleric in a soutane with a book; an industrious administrator at his desk (often with a book); an apotheosized founder of the powerful Society of Jesus. Indeed there were periods during which it seems that Ignatius’s only claim to fame was his role as founder of the Jesuits. Of the various Ignatiuses encountered, I prefer the man with a book, either sitting or standing. I once examined numerous images to ascertain the book’s title. There is no agreement: some have no title whatsoever; others, Spiritual Exercises or Constitutions. More frequently one finds a simple abbreviation AMDG or IHS or, interestingly, Regulae, apparently deemed more important than the previous titles.

In the famous vision at La Storta, God the Father promised Ignatius: ‘I shall be propitious to you in Rome.’ Ironically Ignatius never again left Rome: the pilgrim assumed a desk job. He subsequently corresponded with, among others, his companions Francis Xavier and Jerome Nadal in their travels, and with Alfonso Salmerón and Nicolás Bobadilla in their travails. Would Ignatius have considered such stability a sign of God’s propitiousness? But it truly was for us. He may not have clocked up the frequent flyer miles of his co-founders, but at his desk, he directed the Society of Jesus, and completed the books through which his influence among Catholics and non-Catholics, religious and lay, remains strong.

Frances Murphy

Deputy Editor of Thinking Faith

The Ignatius to whom I have been introduced most recently is the ‘conversational apostle’ of whom Jerome Nadal wrote. He is perhaps a far gentler Ignatius than we might meet elsewhere, but a no less passionate one. He is a man who believes firmly in finding the good in everyone and, in a radical challenge to the gossip circus of so much modern media, in always pointing this good out to others through loving discourse.

He is first and foremost a people person, so much so that when he wrote to the Jesuits present at the Council of Trent he advised them essentially to keep quiet during theological debates and concentrate their efforts on helping others: ‘… teaching children, giving good example, visiting the poor in hospitals, exhorting those around us, each of us according to the different talents he may happen to have, urging on as many as possible to greater piety and prayer.’ This is the same Ignatius who wrote to Jesuits engaged on a secret mission to Ireland in 1541 that their purpose was to ‘engage them in the greater service of God our Lord’. Theirs was not a recruitment drive to bolster numbers or win powerful allies for the Church, but primarily an opportunity to meet people on their terms and to come to know them, in order to lead them to Christ: ‘entering by their door so as to come out by our door’. This is the Ignatius whose example I seek to follow when I pray, ‘Teach me to be generous’.

Dermot Preston SJ

Provincial of the British Province of the Society of Jesus

It is reported that when a British Jesuit was asked, ‘Father, when you die, will you be afraid to meet Jesus?’, the Jesuit’s prompt response was ‘No… but I’m terrified of meeting St Ignatius!’ I suspect many Jesuits would smile and resonate with that. Yes: on the Day of Judgment, Ignatius will be giving us a harder time than Our Lord and Saviour.

An imaginative contemplation? Picture the scene: Jesus is the rather understanding Major-General, mingling with us, his recently-returned troops, back from a demanding (but only partially-successful) mission. He moves among us and shakes hands; he is grateful for our labours, he murmurs encouragement and thanks us for our contribution in difficult circumstances.

But we know that in the shadows of the arrivals lounge, waiting patiently, is Sergeant-Major Ignatius. He is just biding his time, waiting for that amiable Major-General to move on – and then we just know that Ignatius is going to come over and give us ‘a right bollocking’.

Strangely, I find this a comforting image. In a world which is afraid of prophetic contradiction and pushes rampant individualism, hard task-masters are frowned upon because they question our singular pace and push us to keep up to a collective mark. As Superior of the Society, Ignatius famously used to tear strips off his closest colleagues if he felt that they had fallen short of his (and their) standards. But they adored him, because they knew that he understood them, knew what they were capable of, loved them and really only wanted the best for them, ad maiorem Dei gloriam.

Thus, there are times as a Jesuit that things just come together, you fully co-operate with the grace of God, and suddenly you get a big Ignatian hug…and it is all the more precious because it is so unexpected.

Gemma Simmonds CJ

Lecturer in Pastoral Theology and Director of the Religious Life Institute at Heythrop College, University of London

As a daughter of Mary Ward it is hard to over-emphasize what Ignatius means to me, because he is so bound up with our history and our sense of identity. In the aftermath of the Council of Trent, when the Church was busy tightening up on all previous attempts by women to live as apostolic religious in the world outside the cloister, Mary felt called to follow the Jesuit way of life. She knew it was an impossible task, but her experience of the Spiritual Exercises had taught her to trust in where the Spirit of God was leading, outrageous and inachievable though it seemed at the time.

Her attempt was doomed, but here we still are. I write this from South America, where I am working with Mary Ward women from Chile, Argentina, Peru, Ecuador, Rumania and Brazil. Inspired by the Ignatian Exercises and Constitutions they work for the promotion of women, for justice and the pursuit of the reign of God in the toughest of circumstances. As Mary Ward dreamed, ‘I hope it will be seen that women in time to come will do much’. Our history, my history, is written in Ignatian letters ad maiorem Dei gloriam.

Happy Ignatius Day!