The work of a ‘labourer in the English vineyard’ at a time when Catholics were unable to practise their faith as a community has always inspired Elizabeth Harrison, and never more so than during the pandemic, when public celebration of the sacraments was restricted.

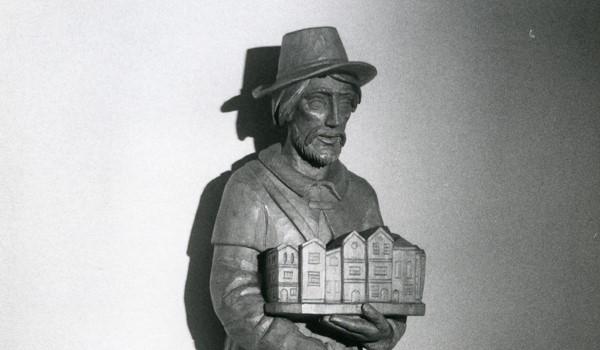

I saw some of the handiwork of Nicholas Owen SJ before I knew what a Jesuit was. When I was a teenager my family visited Harvington Hall, a Tudor manor house in Worcestershire, which has seven ‘priest-holes’ created by Nicholas Owen. During the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I, it was illegal for Catholics to celebrate the Mass or other sacraments. Those Catholic priests who came on missions to England in order to keep the Catholic faith alive and to give people the sacraments were hunted down, arrested and executed, so carpenters like Nicholas Owen worked to make hiding places in some of the great houses in the land where Catholic priests were welcome. So good was Nicholas Owen at his craft, that nobody is certain whether all the priest-holes he made have yet been discovered.

If you have never been to Harvington Hall, I recommend a visit. You can also see some of Nicholas Owen’s handiwork in Sawston Hall in Cambridgeshire, Oxburgh Hall in Norfolk, Huddington Court in Worcestershire, and Coughton Court in Warwickshire, but Harvington Hall has the most examples. There is a hiding place behind some wood panelling, another under a stair, and there is a false chimney which served as an escape route. If you are being shown around on a tour, it can be hard to see where the priest-hole is even when you know it is there.

As a young person, I felt deeply touched to see these signs of people who shared my faith being prepared to risk their lives and hide in these cramped corners for their religious ideals. Apparently, the priests often hid in pairs, because if you were going to face the darkness, in very cramped, airless conditions and in fear for your life, afraid to breathe in case you were detected, you needed a companion. Sometimes the priest-holes led to secret passages so the priests could escape, but sometimes all they could do was hide in a tiny space for as long as it took for the people who were looking for them to finish searching the house, usually without any possibility of food or water. Those searching for the priests used expert masons and carpenters to detect changes in the brickwork and differences in the measurements of woodwork such as panelling, which meant that the hiding-places had to be both ingenious and meticulously made.

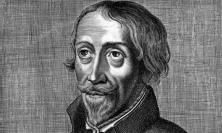

Nicholas Owen SJ is also said to have helped to mastermind the escape of John Gerard SJ from the Tower of London. John Gerard SJ went on to live to the ripe old age of 73, and is unusual among the Jesuits of this period for having escaped execution. He even wrote a memoir.

Owen was eventually caught – he gave himself up to protect Henry Garnet SJ – tortured in the Tower of London and executed. He had worked tirelessly for many long years despite physical illness and disabilities to help to protect those who were fighting for the Catholic faith, both priests and lay people. Needless to say, if a priest were discovered in a person’s house, the occupant and their family would have been subject to arrest as well. John Gerard SJ wrote of Owen: ‘I verily think no man can be said to have done more good of all those who laboured in the English vineyard. He was the immediate occasion of saving the lives of many hundreds of persons, both ecclesiastical and secular.’

We often think that the heroes of that time were the priests who hid in those priest-holes, and rightly so, but we should also remember those who helped to keep the secrets, and of course the master-carpenter himself.

During the pandemic when Catholics were unable to attend Mass (and there were restrictions placed on many types of religious practice, not to mention social interactions), I often thought of everyday Catholics living in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. I remember being able to return to Mass in person after the lockdowns and finding tears in my eyes at the welcome familiarity of being back in church. I don’t think I can ever take the sacraments for granted again. We all made a sacrifice, too, but we were giving up our ability to practise the faith in this way from the comfort of our living rooms, with the option to livestream. We were not living in fear of our lives if we were seen to be practising our faith, as some Christians still are even today. To have lived through the recusant period and to have kept the faith is extraordinary enough, but to have done so and contributed so hugely to the ability of others to practise their faith is more extraordinary still.

Nicholas Owen is one of my favourite saints because, like other Jesuit brothers (such as St Alphonsus Rodrígues SJ and Bl. Francisco Gárate SJ, both doorkeepers), he used the talents he was given in the best way he could, and gave his all for the kingdom through his hard work. I know many Jesuits, priests and brothers alike, who do exactly the same thing, albeit working at a more modern coalface. They know their work might not earn them fame, but they take pride in helping to build the kingdom in whatever way they can. Jesuit formation helps Jesuits to work in so many different spheres – often they will work in many different places and types of work through their lives – and no Jesuits I have met are afraid of getting their hands dirty (literally or metaphorically). They go where the need is.

Most of the time in my life and work I do not feel like a hero (I am not sure I would ever be ready to die a martyr). Nicholas Owen’s life reveals that those who – sometimes literally – chisel away at their everyday work, however menial it might seem to others, can do a great deal of good, as much as those who make great scientific discoveries or create famous pieces of art. We all have our gifts to give, and these are valuable, even when they seem small. Nicholas Owen worked with great humility, of that there can be no doubt, but he also knew his worth and took pride in his work, and so should we.

Dr Elizabeth Harrison is Digital Communications and Resources Coordinator for the Jesuit Institute.