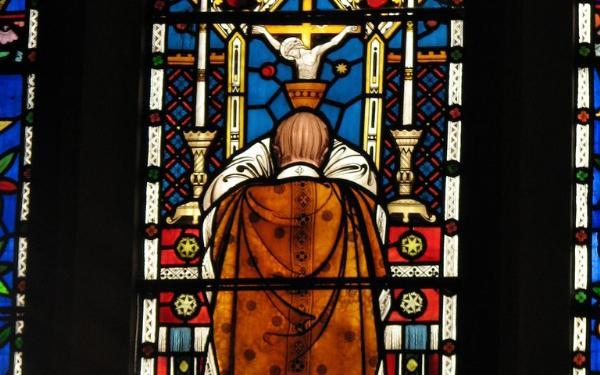

On this day, the feast of St Mary Magdalene, in 1534, Blessed Pierre Favre celebrated his first Mass. Favre was the first of the Companions of St Ignatius of Loyola, soon to become the Jesuits, to be ordained priest. In this second article of a series marking the Church’s ‘Year of the Priest’, French theologian Bernard Sesboüé SJ explains how the specifically Jesuit model of priesthood evolved and was ‘confirmed and enriched’ by the teaching of the Second Vatican Council.

As we reflect on priesthood over the course of this year, it is important to remember that it is a diverse phenomenon. In this article I want to explain how a renewed understanding of priesthood emerges from the life of St Ignatius of Loyola, finding expression in the Society of Jesus which he founded, and how this understanding has, I believe, an important contribution to make today, in the light of the teachings of the Second Vatican Council.

It is often said that the Society of Jesus is a ‘priestly order’, and rightly so. But that can mean any number of things. In an address to the Congregation of Provincials in Loyola in September 1990, the then Father General Kolvenbach used the term ‘presbyteral’. The use of words is never neutral and his choice of vocabulary is very telling.

In fact, the Catholic tradition gives us a double vocabulary for referring to priests. On the one hand that of hiereus, or sacerdos, derived from the Old Testament and taken up again in the Letter to the Hebrews, in which Christ is called the High Priest of the New Covenant which abolishes the old sacrifices. On the other there is that of presbuteros, presbyter, used along with other words in the New Testament to express the originality of ministry in the New Covenant. Thus it suggests the mission of the apostles, marking a distance from the ‘old priesthood’. In some modern languages, this double vocabulary has been reduced to a single one. It is commonplace in France, for instance, to talk of ‘le sacerdoce’.

This goes back to a medieval development which for quite practical reasons strongly bound priesthood to the celebration of foundation Masses, drawing attention to its ‘sacrificial’ nature. This has left a strong imprint on the image of Catholic priesthood. The Council of Trent effectively set it in stone when it opposed the Lutheran understanding of the ‘priesthood of the faithful’ and the priority this gave to the ministry of the Word. This ‘sacerdotal’ model of a priesthood tied to the sacrifice of the Mass is still rather dominant in the Catholic imagination, in spite of a new emphasis in Vatican II.

Vatican II brought back the true significance of what is really sacerdotal: in the New Covenant there is a single priest (archiiereus), Christ, and a single priesthood, which is that of Christ. In the Church, the bishop (episcopos) and the priests (presbuteroi) exercise the ministerial mission of the sole mediation of Christ-priest in the sense that it is a gift from God, whilst all the baptised participate existentially in the one priesthood of Christ (hierateuma), by the grace which makes them able to offer themselves to God as a spiritual sacrifice (cf. Lumen Gentium 10).

So why should we think of Jesuit priests as presbyteral rather than sacerdotal?

The Ignatian sources are surprisingly sober when it comes to the mention of priesthood. Ignatius quite untypically does not seem to have entered into a long decision-making process about being ordained. What are we to make of this comparative silence? Was it the case, as some have thought, that it wasn’t important, perhaps just a necessity with which he went along without too much fuss because it was useful? Or was it was so central to the Jesuit vocation that it was not up for discussion? It is not immediately obvious. I think the real reason is more subtle.

The answer is that in Ignatius’ life a totally original way of combining presbyteral ministry and the religious life is evolving. In the combination each term undergoes a change in meaning. That is why the question is skewed from the outset if we either think of Jesuits as religious first, implying a ‘pure’ concept of religious life which has nothing to do with this ministry; or if we take the ideal of priesthood (which is to say ‘sacerdotal’ ministry) as the cornerstone of the Order. But Jesuits do not constitute a ‘society of priests’. To get an idea of what this new priestly-religious life looks like and how it arises, we have to look back at Ignatius’ life.

Ignatius’ conversion to Christ starts in Loyola with the reading of pious books during his convalescence after being injured in battle in Pamplona. It then plays out in a ‘long retreat’ in Manresa which lasts eleven months. It carries on in a long pilgrimage which leads him hither and thither and eventually to Jerusalem. It is in the holy city that the Church makes a dramatic intervention when the Franciscan provincial refuses to let Ignatius stay. There is an important consequence: Ignatius is forced to rethink his life plans. From now on, the pilgrim asks himself what he is to do: Quid agendum?

This is how he answers the question: ‘In the end, he was inclining more towards studying for a time in order to be able to help souls and was coming to the decision to go to Barcelona’.[1] Note the link between the two parts: to study and to help souls. Ignatius cannot do the second without having done the first. If he has the desire to ‘help souls’ it is because he has already had a taste of the experience before leaving for Jerusalem.

‘Helping souls’ means talking to people about God and helping them to find Him in prayer and in the stories of their lives. By these memorable words Ignatius means exercising various ‘ministries of the word’: spiritual exercises and conversation, catechesis. This link between the studying and helping souls will be a constant throughout his studies.

A third component of what will be the Jesuit vocation appears in the shape of a desire to gather companions for a shared project. We have to hold all three points together, for here we are at the heart of Ignatius’ apostolic project and that of the Jesuits.

Where does ordination to the priesthood come in? As Ignatius recounts in his Autobiography, in 1537, ‘there in Venice those who were not ordained were ordained for mass and the nuncio who was then in Venice gave them faculties: he who was later called Cardinal Verallo. They were ordained under the title of poverty, with all making vows of chastity and poverty’.[2]

Note how and when things happened. First of all, one of the group, the Frenchman Pierre Favre, was already a priest, although he had not been when he met Ignatius and Francis Xavier in Paris back in 1529. Why was he ordained before the others? Quite simply because he had started his studies before them. He says as much in his Mémorial. After a trip to Savoyto see his parents, ‘I returned to Paris,’ he writes, ‘to complete my theology studies; it was in 1534 and I was twenty-eight years old. I made the Exercises and was granted holy orders even though the title deed had not arrived; I said my first Mass on the Feast of Blessed Mary Magdalene (22nd July 1534), my advocate and that of all sinners’.[3] Favre tells us that it is thanks to Ignatius that he let go of his thoughts about marrying, or becoming a physician, lawyer, director, doctor of theology or monk. ‘As I said, the Lord delivered me from all these impulses by the consolations of His Spirit and He made me take the decision to become a priest so as to give myself entirely to His service.’[4] So Favre’s decision is linked not only to Ignatius’ influence but also to a firm desire to share his vocation and the way of life. The case of Favre illustrates that the idea of a priestly apostolate is established in this period.[5]

The ordination of all the other companions takes place during the course of a year spent waiting to travel to Jerusalem. The idea of putting themselves at the disposition of the Pope is still only a fallback. This is the moment, at the end of the studies, when the presbyterate is integrated into the group’s vocation as the normal and necessary outcome of their apostolic intention. In short, the companions become a group of priests prior to placing themselves at the disposal of the Pope and also before they take the decision to found a religious order. The first Jesuits were priests before they were religious. You cannot say that ordination is just added on to Jesuit religious life for form’s sake. The companions present themselves as ‘poor pilgrim priests’, a description which still evokes their intention of going to Jerusalem. For the moment, they continue as before with their preaching ministry in northern Italy. This fits in with the concrete pattern of the priestly ministry that they want to live out. But it emerges gradually that they are also hearing confessions.

They seem to be in no hurry, it will be noted, to celebrate Mass. The group waits forty days. This point has to be interpreted both according to the customs of the time, and as a reflection of their desire for an intense spiritual preparation for an act which they regard as central. It would be a huge error to see in this an expression of indifference. Ignatius decides to wait a whole year, doubtless so as to be able to celebrate his first Mass in Bethlehem. What is more, he tells us that this period was one of an intense experience of graces, ‘most of all, when he began to prepare himself to be a priest in Venice, and when he was preparing himself to say Mass. Throughout all these journeys, he had great supernatural visitations of the kind that he accustomed to having while he was in Manresa’.[6] The reference to Manresa, the place where his spiritual life really took off, shows just how important ordination is to him.

Finally, when plans to go to Jerusalem fall through, it is a group of priests which, at the end of November 1538, places itself at the disposal of the Pope to be sent wherever in the Lord’s vineyard it will seem good to Him. The companions insert themselves at the heart of the hierarchical institution of the Church. What they are looking for from the Pope is very much in the domain of canonical mission and of jurisdiction. The little group is a modest presbyterium, an ‘extraordinary’ presbyterium of the Bishop of Rome in so far as he has responsibility for the whole of the Church, a presbyterium of ‘reformed priests’, which is what the Church most needed in the period. From the start, the companions will receive missions and ministries which belong to priests, part and parcel of the hierarchical mission of the Church.

Only in 1539 do the companions take the decision conclusively to found a religious order, with obedience to a superior to prevent the centrifugal missions they received from the Pope from destroying their little band. To those who say that the decision to have themselves ordained priests was the result of a merely sociological reason, one could reply that this new decision was of the same sort. But I would not agree with either statement. Rather, the Society transforms everything it incorporates into itself, presbyterate as well as religious life. It is an apostolic motivation, a sense that the mission is what it is all about, which draws the one and the other successively into itself. If it is true to say that presbyteral ordination is the means to an apostolic end, exactly the same goes for the foundation of an Order.

The Formula of the Institute approved by the Pope in 1540 clearly expresses one goal: apostolic mission centred on the official proclamation of the Word, the works of the Word and the administration of the sacraments, mentioned in the example of confessions. The governing image is the ministry of the apostles who surrounded Jesus and were sent out by Him. Jesuit canon lawyer, Michel Dortel-Claudot sums up the central convictions of the first generation of Jesuits like this: ‘it is the apostolic aim which structures the Society and is the heart of its religious life. The Society is the first order of this type. The Society is, as are the other “clerks regular”, an order of priests, but in a different way from them because the presbyterate of the Society is orientated first of all to apostolic mission.’

Of course not all Jesuits are priests. Early on we see the idea emerging of temporal coadjutors, more normally known as brothers, and of course there are novices and scholastics. But all are part of the apostolic mission. The core of the Society is indeed that of a presbyteral and instructed body. There is a place for non-priestly members of the Society but as coadjutors in a presbyteral body. These brothers (as well as the scholastics and novices), put themselves at the service of what is essentially a presbyteral form of mission in the Society.

It is well known that one of the great achievements of Vatican II was to recover the New Testament perspective of apostolic ministry, rooted in the ideas of being sent and of mission. The Council was obliged to shift the terms around from the moment it gave its rightful place to the ‘priesthood of all believers’ and treated the ordained ministry from the point of view of the bishops, and no longer from that of the presbyter understood first and foremost as sacerdos. Thinking through ministry from the point of view of the mission of the apostles as continued today by the Church’s triple ministry of Bishop, priest and deacon, the Council rehabilitated the term ‘presbyter’, meaning a co-operator of the bishop. This has helped make clear that apostolic or ordained ministry is defined first of all by its meaning and only then by its tasks. This meaning is an expression of the initiative of Christ in relation to His Church; the bishop and the priest are and symbolise ministerially, the gift of Christ-as-Head. Father General Kolvenbach points out that the Jesuit vision of priesthood to some extent anticipated the 20th Century insight: ‘The view of Vatican II fully confirmed and enriched the figure of the presbyter as it is understood and lived in the Society of Jesus.’[7]

So, in summary, the Society is an apostolic body of a presbyteral type. It participates in the mission of the Church, giving to it ‘instructed priests’ who officially proclaim the Gospel in ways which always need to be reinvented. The kind of presbyteral ministry which it has chosen right from the start corresponds exactly to the intuitions of Vatican II.

(Translated by Damian Howard SJ)

Bernard Sesboüé SJ is a dogmatic theologian, author of many books and emeritus professor in the Theology Faculty of the Jesuit Centre Sèvres in Paris.

[1] Autobiography 50. St Ignatius of Loyola. Personal Writings [SILPW]. Translated with an introduction by Joseph A. Munitiz and Philip Endean. Penguin Books, 1996, p36. Emphasis added.

[2] Autobiography 93, SILPW p59. ‘They’ were Bobadilla, Lainez, Xavier, Codure, Simon Rodriguez and Ignatius; Salmeron was ordained deacon but, given his tender years, had to wait for the priesthood.

[3] Mémorial 14.

[4] Mémorial 14.

[5] Le récit du pèlerin. Autobiographie de saint Ignace de Loyola. Translated by A Thiry, Bruges : 1956, p122.

[6] Autobiography 95, SILPW p.60.

[7] Allocution to the Congregation of Provincials, Loyola, 1990, No. 8.

Read more of Thinking Faith’s series for the Year of the Priest:

![]() Jesus Our Priest – Gerry O ’Collins SJ

Jesus Our Priest – Gerry O ’Collins SJ

![]() Re-imaging priesthood – Bishop Greg O’Kelly SJ

Re-imaging priesthood – Bishop Greg O’Kelly SJ

![]() The Hiddenness of Priestly Life – James Hanvey SJ

The Hiddenness of Priestly Life – James Hanvey SJ

![]() Matthew Power SJ’s review of Priesthood: A life open to Christ

Matthew Power SJ’s review of Priesthood: A life open to Christ