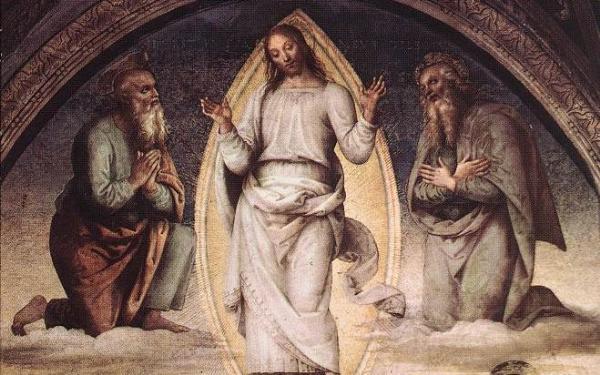

This Sunday’s gospel reading is the account of the Transfiguration of Our Lord. Luke tells us that the disciples who witnessed Jesus’s encounter with Moses and Elijah were terrified by what they saw and heard, but Jack Mahoney suggests that this experience was one that nourished and encouraged them. What can we learn from this event, as Peter, James and John did, about the Christ towards whom we journey throughout Lent?

Some years ago as I was meditating on the Transfiguration of Our Lord I had a sudden thought about it: I realised that it could have taken place at night. This could shed new light on a number of the details in the story, and could help us better understand and appreciate this passage from St Luke’s Gospel, which is chosen as the gospel for the Mass of the Second Sunday in Lent.

In reading the accounts of the scene as it is described, with slight differences, in all three synoptic gospels – Mark (9:2-8), Matthew (17:1-8) and Luke (9:28-36) – I could find no indication of the time of day or night at which it was supposed to have occurred. But I was thrilled then to read Luke begin his description of the next episode in his Gospel: ‘On the next day, when they had come down from the mountain . . .’ (9:37). It looked as if Luke might have been trying to tell us, as I had thought, that the manifestation of Jesus’s glory and his conversation with the two great figures from the history of his people, Moses and Elijah, took place during the night.

Exodus to Jerusalem

As we saw last week, Luke likes to show Jesus interrupting his missionary activities at times to withdraw and pray to his Father (3:21; 5:16; 9:18; 11:1). This would occur often at night and on a mountain top (6:12): a place where one can feel risen above the trivia of daily life and somehow closer to God, and also a traditional location in the history of Israel where the presence of God was specially experienced. The outstanding instance of Jesus spending the night in prayer would be the night of his anguish on the Mount of Olives just before his arrest (22:39-46). This event of the Transfiguration (9:28) could have been another such night of prayer, which seems intended to anticipate and parallel the night of the agony in the garden. It was a time to strengthen Jesus and his close apostles for what was to come, making them aware that the God of Israel was supporting him, and was endorsing his proposed journey to his death in Jerusalem. Jesus had just foretold this (9:21-2) and he would prophesy it further in Luke’s Gospel as we see him gradually pursue his journey to his destiny (9:43-4; 13:33; 18:31-3).

As in the account of the Transfiguration in the other synoptic gospels, Jesus in Luke’s version chose his three closest disciples, Peter, James and John, to accompany him up the mountainside. But it is only Luke who informs us that Jesus’s purpose was to engage in prayer (9:28), and again only in Luke (9:29) are we told that it was while Jesus was praying to his Father that he experienced the Transfiguration, that ‘the appearance of his face changed, and his clothes became dazzling white’ (9:29), which would be all the more striking if this occurred at night. Luke also described this event as the three apostles seeing Jesus’s ‘glory’ (9:32). It was almost as if Jesus’s divinity, normally concealed, was permitted to shine through for once and to transform his physical appearance. Or, it may have been Luke showing something of the future glory which would come to Jesus after his crucifixion, about which he was going to speak with the two great figures from Israel’s history, Moses and Elijah, who ‘appeared in glory’ with him (9:31). As the risen Christ was later to ask his two dispirited disciples on the road to Emmaus, ‘Was it not necessary that the Messiah should suffer these things and then enter into his glory?’ (24:26).

The fact that Jesus’s appearance was changed during his Transfiguration is one reason why some commentators have suggested that this scene actually took place after the resurrection, some time during the forty days when, Luke tells us, the risen Christ continued to appear to his apostles and speak to them about the kingdom of God (Acts 1: 3). Various passages in the gospels indicate that the resurrection from the dead changed Jesus’s physical appearance so that he was not recognised at first (e.g. Mt 28:17, Lk 24:17, Jn 20:14, 21:4). This seems to have occurred here in the Transfiguration scene, and also in the walking on the water (Mk 6:49), leading some commentators to conclude that both scenes date from the period after the resurrection. In the case of Luke’s description of the Transfiguration, however, the glory of Jesus is shared by Moses and Elijah in looking ahead with Jesus to his exodos, or ‘departure which he was to accomplish in Jerusalem’ (9:31), so Luke seems to be suggesting that this event occurred before the resurrection. Exodus was the historic term which, of course, described the great departure of the people of Israel from their enslavement in Egypt, although in this context it might mean the death of Jesus, or perhaps more likely the whole return of Jesus back to his Father in heaven through his death and his resurrection.

When we read in the Gospel about Jesus conversing with someone we tend to think that he is addressing them, but it could imply that they are also speaking to him. The description given by Luke alone (9:31) of Jesus’s conversation with Moses and Elijah fills out what seems to have been only implicit in the other gospel accounts of the event (Mk 9:4; Mt 17:3): that these two major figures from the Old Testament and the history of Israel were confirming Jesus’s own conclusions about his future and were enlightening him on what was going to happen in Jerusalem, with its significance for him and for the people of Israel he was about to save. Both of these men had been prophets. Moses, the great leader and liberator who had experienced God on the mountain (Ex 24:15-18), was considered the first and greatest of the prophets to Israel and one ‘whom the Lord knew face to face’ (Dt 34:10-12). Elijah was a celebrated prophet and miracle worker (1 Kgs 17:1-17) who opposed Ahab, king of Israel, and his wife Jezebel and routed the prophets who served the false god Baal (1 Kgs 18:40), alienating Jezebel and taking refuge on Mount Horeb ‘the mount of God’ (1 Kgs 19:1-10). He later denounced and successfully resisted Ahab’s successor (2 Kgs 1:1-17) before being taken up dramatically to heaven (2 Kgs 2:11), an event that led to the tradition among the Israelites that Elijah would return some day (Mal 4:5). This led to the popular conjecture recorded by Luke that Jesus, who was becoming known by his disciples as ‘a prophet mighty in deed and word before God and all the people’ (Lk 24:19), and who was considered as possibly the great prophet whom Moses foretold the Lord would raise up in the future like him (Dt 18:15; Lk 7:20), might even be Elijah returned (Lk 9:8,19).

It is good for us to be here

Peter, James and John witnessed Jesus conversing with Moses and Elijah, although, Luke tells us, they ‘were weighed down by sleep’ (9:32), a detail which again suggests that it was night time, and which will later be paralleled in the description of the disciples falling asleep during the agony in the garden (22: 45-6). As Moses and Elijah were departing from Jesus, Peter apparently wanted to keep them there, and he observed to Jesus that being there was good for him and his fellow disciples, so much so that he suggested they set up three tents for Jesus, Moses and Elijah (9:33). According to Luke (9:33), following Mark (Mk 9:6), Peter did not know what he was saying here. However, he was possibly referring, even unconsciously, to the Jewish Feast of Tents, or Tabernacles, which John 7:2-10 tells us Jesus attended in Jerusalem. This was the annual harvest festival which the Jews were accustomed to celebrating (Dt 16:13-17), when for seven days they would ‘live in booths’ constructed from branches (Lev 23:39-43), glorifying God in remembrance of their nomadic time in the desert.

However, Peter’s proposal was upstaged by the appearance of a cloud which now came and overshadowed the disciples, terrifying them (9:34), while from the cloud a voice announced ‘This is my Son, my Chosen; listen to him!’ (9:35) A cloud appearing on a mountaintop was a privileged experience in Jewish history, signifying the presence and activity of God. Famously, when Moses was establishing the covenant between God and his people and was summoned by God up the mountain, ‘the glory of the Lord settled on Mount Sinai, and the cloud covered it for six days,’ and on the seventh day God addressed Moses out of the cloud (Ex 24:15-16). Now this was not God issuing his will to a terrified Israel through the ten commandments as he had done on the mountain top through Moses (Ex 19:16-20:21); it was God designating Jesus, as he had earlier done at his baptism (3:22), as his chosen spokesman and prophet to express his will to his people. In Jesus’s being addressed as ‘my Chosen one’, only in Luke’s account of the Transfiguration (9:35), we are being offered a further clue to the identity and role of Jesus by this echo of the description foretold by that other great prophet, Isaiah (Is 42:1-4), concerning:

my servant, whom I uphold,

my chosen in whom my soul delights;

I have put my spirit upon him;

he will bring forth justice to the nations . . .

he will faithfully bring forth justice.

He will not grow faint or be crushed

until he has established justice in the earth,

and the coastlands wait for his teaching.

This could help to explain, then, why Luke continues that ‘when the voice had spoken, Jesus was found alone’ (9:36). It was almost as if Moses and Elijah, whom some commentators see as personifying here the whole of the Law and the Prophets of the people of Israel, were now departing the scene, their mission and role now accomplished. They had handed over to Jesus and the new covenant the future destiny of their people, and, indeed, of the whole world, which Jesus was now leading under God to a new kingdom of divine rule and justice.

Listen to him

As we consider the significance of this passage from Luke’s Gospel, several points can emerge. One is that we are being strengthened and confirmed, as were the chosen disciples – and even Jesus himself – in our belief in the mission of Our Lord to suffer and die for our sake, but also to survive and return to a glorious risen life in the power of his Father. This belief can sustain us as we journey through Lent. We can also appreciate the special nuances which Luke brings out in his account of the Transfiguration: the importance of prayer in the life of Jesus, and therefore in ours too; the tiredness of the disciples and the other clues that the Transfiguration took place one night while Jesus was at prayer; and the final pointing to Jesus as the ‘suffering servant’ of Isaiah (Is 53:2-11), giving suffering a positive and creative construction, as pointed out in Vatican II’s closing message to the poor, the sick and the suffering: ‘you are the brothers of the suffering Christ, and with Him, if you wish, you are saving the world.’

Another point to consider is Peter’s feeling that it was ‘good’ for the disciples to be there on the mountain top along with the glorified Jesus and Moses and Elijah, and that when Moses and Elijah were about to depart Peter wanted to keep them all together and to prolong the experience. This recalls the point beloved of traditional retreat givers, that we may on occasion experience a feeling of spiritual pleasure or contentment, or what St Ignatius of Loyola called ‘consolation’ in prayer; that we want to maintain the spiritual glow of devotion and are sorry to feel it go. How are we to handle what we may call the ‘re-entry’ problem, that of reluctantly returning from a state of spiritual delight to the mundane realities and distracting chores of daily life? Peter did not appreciate that the shared experience of the Transfiguration was to prepare him and his fellows, as well as Jesus, for the distress and desolation which they were soon to experience when Jesus completed his journey to Jerusalem, as Luke points out (9:31). The point is well captured by St Ignatius in his comment on ‘rules for discernment of spirits’ in the first week of theSpiritual Exercises: ‘let any who are in consolation think how they shall carry themselves in the desolation that will come afterwards, gathering new strength for that time.’ That seems to be Luke’s point for his readers, and the Church’s point for us at this stage in Lent: assurance and divine encouragement from the Transfiguration of Jesus, to keep going in following Jesus and to trust God in whatever future he may have in mind for us.

Jack Mahoney SJ is Emeritus Professor of Moral and Social Theology in the University of London and author of The Making of Moral Theology: A Study of the Roman Catholic Tradition, Oxford, 1987.

![]() Keeping Lent with Saint Luke

Keeping Lent with Saint Luke

![]() The Temptation of Jesus

The Temptation of Jesus

![]() ‘Repent or Perish’

‘Repent or Perish’

![]() The prodigal son and his jealous brother

The prodigal son and his jealous brother

![]() The Woman Caught in Adultery

The Woman Caught in Adultery

![]() The Passion According to Saint Luke

The Passion According to Saint Luke