As we hear Saint Luke’s account of the Passion this Palm Sunday, we are invited to walk with Jesus in the final stages of his journey to the cross. Jack Mahoney SJ has been helping us to think and pray about the Sunday gospels throughout Lent, and now looks at the picture that Luke paints for us of Jesus’s arrest, trial and crucifixion. By focusing on the Lucan trends with which we have become familiar over recent weeks, how can this narrative help us to understand that Jesus ‘loved me and gave himself for me’?

Try to imagine yourself as an educated member of the Roman Empire reading Luke’s account of the birth, life and teaching of Jesus of Nazareth, and at the end asking Luke: ‘If all that you write is true about the character and the behaviour and teaching of this good man who claimed to be a prophet of his god, how do you explain his death as a criminal condemned and crucified by the local Roman authorities?’ We can consider Luke setting himself the task of answering this question as he wrote for Gentiles the concluding section of his gospel, which described the arrest, trial and execution of his divine Master. The Passion According to Saint Luke is the reading for this coming Sunday, the final Sunday of Lent, which is called Palm Sunday and is the beginning of Holy Week in which we are invited to reflect on and pray about the painful death that Our Lord accepted.

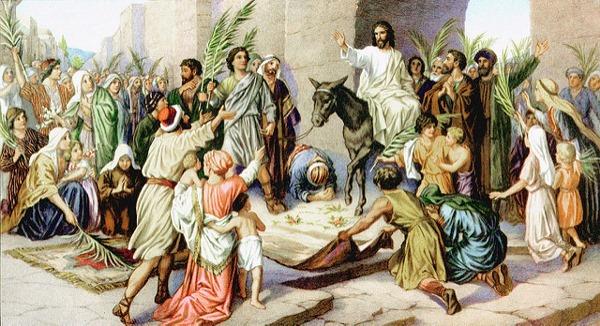

Each of the four gospels contains a major concluding section devoted to describing the arrest, trial and execution of Jesus in Jerusalem, in which all follow roughly the same structure and chronology, differing only in minor details. It is thought, in fact, that the gospels all started simply as accounts of the Passion and Death of Jesus written down for the benefit of preachers and adult converts to Christianity, and that these in time were expanded by adding introductory sections to describe the teaching and deeds of Jesus in his public life leading up to his death. All of the gospels begin their Passion section by describing the final triumphal entry of Jesus into Jerusalem on what we know as Palm Sunday.

From triumph to tragedy

For Luke, this entry into Jerusalem was the culmination of Jesus’s mission to Israel (Lk 9:51): it was here that he felt, like previous prophets, called to confront the religious leaders of his people, to recall them to a more faithful adherence to the God of their fathers, and to die in the attempt (13:33); and it was from Jerusalem that Luke in his sequel, The Acts of the Apostles, would describe the spread of Christianity throughout the Mediterranean. The Gospel of Mark is followed by the other gospels in describing the triumphant procession of Jesus with his disciples riding in honour from Bethany into Jerusalem, with many people spreading their cloaks and branches of trees on the ground ahead of him. Mark has the crowds acclaim ‘Hosanna! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord! Blessed is the coming kingdom of our ancestor, David! Hosanna in the highest heaven!’ (Mk 11:1, 7-10). Matthew renders this as ‘Hosanna to the Son of David. Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord [Ps 118:26]. Hosanna in the highest heaven’ (Mt 21:8-9), with no reference to the kingdom of David. Luke, however, has the crowd of disciples and others explicitly refer to Jesus himself as king, changing Ps 118:26 from: ‘Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord!’ to ‘Blessed is the king who comes in the name of the Lord’ (Lk 19:38); while John, probably written last of all, informs us that a great crowd took branches of palm trees (providing us with the origin of the name Palm Sunday), and acclaimed Jesus, shouting, ‘Hosanna! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord – the King of Israel’ (Jn 12:12-13).

The picture painted is of large crowds of Passover pilgrims giving an impressive welcome to the capital city to the famous prophet from Nazareth in Galilee. According to Luke, he is being recognised as a king because of all his ‘deeds of power’ (19:37) and is being acclaimed by an enthusiastic throng of people who are loud in their praise, but who will soon be manipulated by their religious leaders to change their cries and call for Jesus’s crucifixion. It is in keeping with Luke’s concentration on the hostility coming from the Pharisees that he has them protest at the acclaim, and demand that Jesus order his disciples to stop (Lk 19:39), presumably referring mainly to the political dynamite in a Roman-occupied territory of the people acclaiming Jesus as their king. But he would not stop them, or said he could not (19:40); and on they went in noisy triumph until Jerusalem came into view. At the sight of the city Jesus wept, aware that it was going to reject him (Lk 13:34) and dreading its tragic destruction by the Romans (Lk 19:41-44). Luke alone tells us of this event in his concern to stress Jesus’s humanity, as he also alone later records Jesus’s sympathy for ‘the daughters of Jerusalem’ who wept at his suffering on the way to Calvary (23:27-31).

For Luke, Jesus’s first act on entering Jerusalem was to proceed to the temple, which from his youth he had known as ‘my Father’s house’ (2:49), and to take possession of it, forcefully driving out from it all the people who were selling things there, and condemning them for turning God’s house of prayer into a bazaar (19:45-6). For the next few days before the Passover, Jesus was to teach in the temple (20:1-21:36), enthralling an audience who got up early each morning to listen to him (21:38); and only fear of whom prevented the chief priests, the scribes and the leaders of the people from getting rid of this troublemaker (19:47-48; 22:2).

As the celebration of Passover drew near, however, Luke informs us that the chief priests and the scribes were looking for a way to kill Jesus, and that Satan, who we were warned at the beginning of Jesus’s ministry would return to tempt Jesus (4:13), was preparing for his final assault by recruiting Judas Iscariot to betray his master to the chief priests and the temple police (22:2-3). All four gospels describe the Last Supper which Jesus was to share with his close disciples, but we are indebted to Luke for some particular details which only he provides. He recalls, for instance, how Jesus began by informing his apostles how much he had been looking forward to sharing this Passover with them ‘before I suffer’ (22:15).

Establishing the new covenant

Jesus then set about instituting the Eucharist. John does not include this in his account of the Last Supper, but we have four slightly differing versions from Mark, Mathew, Luke and St Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians (1 Cor 11:23-26). In each case we have only a minimal, even skeletal description of the events, possibly partly for reasons of religious discretion; and scholars generally agree that the minor differences to be found show that each version that we possess derives from one of the liturgical traditions of ‘the breaking of the bread’ which were developing independently in the different churches when the gospels were being written down. A comparison of the four accounts shows similarities between Luke’s and Paul’s versions, indicating Luke’s connection with St Paul: both observe that Jesus took the cup of consecration only when supper was finished, and both stress explicitly the blood of Jesus as belonging to the ‘new’ covenant (1 Cor 11:25; Lk 22:20), as well as recording Jesus’s instruction to the apostles to ‘Do this in remembrance of me’ (1 Cor 11:24 and some manuscripts of Lk 22:19). It appears that for Luke, just as the old covenant between God and Israel is about to be replaced by a new one with the new Israel (Jer 31:31), so the annual symbolic celebration of ancient Israel’s liberation, the Passover meal, is now to be replaced for Jesus’s followers by the Eucharist, in which Jesus shares his body and his blood with his followers and enjoins them to keep celebrating it in his memory. Luke does not add, however (nor do Mark or Paul), that the blood of Jesus is to be poured out ‘for the forgiveness of sins.’ This is found only in Matthew’s account (26:28), where it possibly reflects the preoccupation with sin which is to be found in Matthew’s Gospel, and presumably in his Jewish-Christian community (Mt 1:21, contrasted with Lk 1:31 and 2:21). Covenant rather than sacrifice appears to be at the centre of Luke’s Last Supper.

When supper was concluded, Jesus and his disciples retired for the night as usual to the Mount of Olives (22:39), where Jesus, again as usual, devoted himself to prayer to his Father, as we discussed in our reflection on the transfiguration. On this occasion Luke draws our attention to the human apprehension of Jesus as he begs his Father, if he so willed, not to ask Jesus to drink the cup of suffering which he fears is going to be offered him, but concludes that he would accept whatever was his Father’s will (22:41-44). (Here, some manuscripts of Luke add a passage which is greatly disputed: that in the stress of his agony Jesus’s sweat was like drops of blood, but that an angel appeared to him and strengthened him [22:43-44]). Now resolved to accept his death as his Father’s will, Jesus returned to his sleeping disciples and shortly afterwards a ‘crowd’ arrived, comprising the chief priests, the officers of the temple police and the elders (22:52), led by Judas, and they arrested Jesus. Luke follows Mark (14:14:47) in recording the disciples’ weak attempt to resist and the wounding of a slave of the high priest, but only Luke informs us that Jesus healed the wound, rejecting any attempt to prevent his being arrested (22:47-51) and being led to the house of the high priest (22:54).

The complicated chronology of Jesus’s Jewish trial and the false charges introduced against him by the religious leaders are simplified by Luke, compared with Mark (Mk 14:53-64). Luke prefers first to highlight Peter’s threefold desertion of Jesus, of which the impetuous Peter had been forewarned by Jesus at the Last Supper (22:31-34). Luke tells us that the apostles’ leader was forgiven almost immediately as Jesus turned from his accusers to direct a private look at Peter, and straightaway his betrayal was bitterly repented of (22:55-62). Jesus himself was mocked and beaten up by his captors (22:63-5), and the next day, Luke tells us, he was brought formally before the Jewish council, who demanded to know if he was the Messiah. When Jesus agreed that he was the ‘Son of God’ they were satisfied that he merited death in Jewish law. Being aware, however, that only the Romans had the authority to impose the death penalty in occupied territories (Jn 18:32), they led Jesus off to the Roman authorities in the person of Pontius Pilate, determined to have him found guilty of a capital charge and be put to death (22: 66-23:1).

As mentioned previously, Luke’s Gospel was written to commend faith in Jesus to Gentile and Roman readers and it is understandable that it gives considerable attention to the Roman trial of Jesus by Pilate – in contrast with Mark, Matthew and even John – showing that the Roman procurator tried on no fewer than three occasions to resist the Jewish religious establishment and acquit the accused. Jesus’s innocence is highlighted repeatedly by Luke, and the political charges laid against him by the whole assembly before Pilate are obviously contrived, including the charge that he claimed to be a king (23:1-2). We may recall, however, that in Luke the crowds on Palm Sunday did change the psalm to acclaim Jesus as ‘the king who comes in the name of the Lord’, to the political scandal of the Pharisees (19:38-39). Perhaps this gave some credibility to the charge, for it was this allegation that Pilate picked up in asking Jesus if he was the king of the Jews (23:3). Hearing also that Jesus had started his prophetic activities in Galilee, Pilate sent him off to be dealt with by Herod, the ruler of Galilee (3:1), for whom Jesus had little time, referring to him as ‘that fox’ (13:32). In fact, Herod and his thugs could get nothing out of Jesus, and he was returned to Pilate in ridicule (23:6-13).

The Roman governor next attempted to release Jesus by declaring him innocent against the popular swell of rejection (23:13-16) and by offering to extend to him the traditional pardon that was given at Passover time to a convicted criminal; but ‘the chief priests, the leaders and the people’ demanded that Pilate release another criminal, called Barabbas, instead, and have Jesus crucified (23:13-21). Yet once more Pilate protested he could find no basis for the sentence of death and he now proposed to have the accused flogged and released, a common Roman procedure of acquittal. Yet again, however, he could not prevail and he ultimately surrendered to popular pressure: he gave his verdict ‘that their demand should be granted . . . and he handed Jesus over as they wished’ (23:22-25).

Luke leaves out mention of the scourging of Jesus by the Roman soldiers at Pilate’s orders and of his being ridiculed by them with a purple kingly robe and a derisory crown woven of thorn branches, which other gospels mention here (Mk 15:15-20; Mt 27:28-31); and he welcomes the attempt made by the other evangelists to soften the suffering of Jesus by describing how the Romans recruited an innocent bystander, Simon of Cyrene, to carry the cross for him (23:26). It was now, as we saw earlier, that the following crowds included a number of Jerusalem women bewailing the fate of Jesus, but to whom he delivered his advice to be concerned more for what was to happen to them (23:27-31). Again, it is only in Luke’s version of the crucifixion – and not in all the manuscripts – that when Jesus was nailed to the cross, in his concern to forgive his enemies (6:27-28) he prayed: ‘Father, forgive them for they do not know what they are doing’ (23:3), a prayer which Luke would use later as a model in describing the execution of Jesus’s follower, Stephen, by the Jewish leaders (Acts 7:60).

Further evidence of Jesus’s continuing personal concern for others emerges from the encounter with the two criminals who were crucified alongside him: of the derision of the one but the rebuke by the other at his fellow-criminal attacking this man who had done nothing wrong. Then occurs, only in Luke, the famous exchange between the ‘good thief’ and Jesus. In the light of the inscription posted on Jesus’s cross that he was ‘the King of the Jews’ (23:38), the thief asked, possibly in belief but possibly just in sheer good-heartedness: ‘Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom’; and Jesus, the saviour of humanity at the point of death, responded out of the depth of his love: ‘Truly, I tell you, today you will be with me in Paradise’ (23:39-43). A final touch we can note in Luke’s description of the death of Jesus is that instead of praying the psalm which appears in Mark and Matthew to express from the cross the feeling of dereliction at being abandoned by God (Ps 22:1) – although it should be noted that the psalm in fact ends on a note of victory (Ps 22:27-31) – Jesus ends his life in peace and fulfilment, commending his spirit trustingly into his Father’s hands (23:46; Ps 31:6; Acts 7:59). Finally it was a Roman centurion, who saw what had taken place, who is invoked as a final witness for Jesus, praising God and saying: ‘Certainly this man was innocent.’ (23:47).

‘He loved me and gave himself for me’ (Gal 2:20)

As the Father would look down from heaven on his crucified son – as depicted in Salvador Dali’s famous, Glasgow-based Christ of Saint John of the Cross– he would see his ‘chosen one’ to whom he had asked everyone to listen (9:35; Is 42:1), a man who lived a life of total integrity and faithfulness in devoting himself to recalling Israel to God and introducing God’s kingship. It could not end there, as Luke was well aware and as he reported Jesus himself prophesying more than once, to the bewilderment of his disciples (9:22; 18:31-34). Everyone connected with Jesus, Luke reports, stunned that all this could have happened, ‘stood at a distance, watching these things’ (23:49).

Believers who follow the account of the death of Jesus are invited by the Church to share his thoughts and feelings on Good Friday, not only the humiliation and the painful conditions to which he was subjected and under which he suffered, but also his strong persisting faith in his Father’s love and support throughout all his sufferings. There are many thoughts that can occur to each of us in the intimacy of our life with God, perhaps as we recall how, in Luke, Jesus is invariably shown as so closely concerned with individuals in need. What may emerge above all, perhaps, may be the simple conviction of St Paul that Jesus ‘loved me and gave himself for me’ (Gal 2.20).

In his Spiritual Exercises, St Ignatius of Loyola has exercitants, as they meditate on their sins, kneel before a crucifix and ask themselves three searching questions: What have I done for Christ? What am I doing for Christ? What must I do for Christ? I have heard it suggested that this is a typically masculine, action-orientated approach; but I feel that Mary Magdalene, for one, would have had no problem in understanding the questions or what they implied. Ignatius closes with words we may find appropriate ‘Seeing the state Christ is in, nailed to the Cross, let me dwell on such thoughts as present themselves’.

Jack Mahoney SJ is Emeritus Professor of Moral and Social Theology in the University of London and author of The Making of Moral Theology: A Study of the Roman Catholic Tradition, Oxford, 1987.

![]() Keeping Lent with Saint Luke

Keeping Lent with Saint Luke

![]() The Temptation of Jesus

The Temptation of Jesus

![]() The Transfiguration of Jesus

The Transfiguration of Jesus

![]() ‘Repent or Perish’

‘Repent or Perish’

![]() The prodigal son and his jealous brother

The prodigal son and his jealous brother

![]() The Woman Caught in Adultery

The Woman Caught in Adultery