Greed is good: true or false? Michael Kirwan SJ tackles this question by watching Danny Boyle’s Shallow Grave, in which he sees traces of a much older morality tale. In week 5 of our Lenten series, we ask: is there really anything wrong with seeking to acquire goods to satisfy our natural appetites?

So, who are we to believe, Geoffrey Chaucer’s Pardoner, or Gordon Gekko? The fourteenth-century Pardoner insists to his fellow pilgrims that radix malorum est cupiditas (the love of money is the root of all evils) and reinforces the message with a powerful morality tale. Listen on the other hand to Gordon Gekko, Michael Douglas’s character in the 1987 film, Wall Street, and we famously hear that ‘greed is good’. Some of us can probably recite his famous speech to shareholders:

I am not a destroyer of companies. I am a liberator of them! The point is, ladies and gentleman, that greed – for lack of a better word – is good. Greed is right. Greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms – greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge – has marked the upward surge of mankind.

It is interesting that we associate this kind of naked defence of greed with the spiritually dismal 1980s (just as we were assured by Philip Larkin that ‘sexual intercourse began in 1963’). This mix of social Darwinism and an intoxicating Nietzschean ‘will to power’, leaving the strongest and fittest at the top of the pile, did hold our attention for a while.

Chaucer’s Pardoner tells a different tale, of three young ‘rioters who did nothing but engage in irresponsible and sinful behaviour’. On a drunken excursion they find, under a tree, eight bushels of gold coins. They draw lots to decide which one of them will run back to the town to fetch bread and wine, while the other two protect the treasure, which they will then take home at nightfall. When the youngest is sent on the errand, his comrades decide they will kill him and split the treasure between them. Unfortunately, the youngest has also decided on treachery: he buys poison, which he pours into the wine bottles. When he returns, he is stabbed to death by his comrades, who, before burying the body, decide to sit down and enjoy the wine …

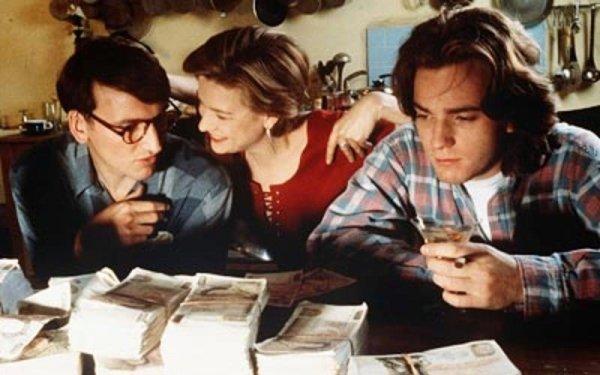

Radix malorum est cupiditas. The theme of greed’s corrosive power is reprised in Danny Boyle’s debut feature film, 1994’s Shallow Grave, in which the lives of three Generation X flatmates in Edinburgh are changed forever by a similar stroke of ‘good fortune’. The trio, Alex, David and Juliet, are just as obnoxious as Chaucer’s three revellers: their self-absorbed, cynical closeness is maintained at the cost of a vicious contempt of others, not least the various applicants for their vacant fourth room. Eventually they admit Hugo, a reserved and aloof lodger, whom they find dead of an overdose in his room several days later. They also find a suitcase full of cash. Almost inevitably, they decide to cover up Hugo’s death and keep the money for themselves; this involves disposing of Hugo’s body in a gruesome manner, namely sawing off hands and feet and smashing teeth so as to evade identification (all three find the task repugnant, so they draw lots).

Their friendship unravels into a morass of paranoid suspicion, just as in the Pardoner’s morality tale. The love triangle between the two men and Juliet doesn’t help matters, and the stakes are raised when the police and the homicidal drugs dealers start to close in. A frenzied struggle breaks out, which only one of the three survives. As with The Talented Mr. Ripley (another film considered in this Lenten series), we are left to consider the mysterious fragility of our attempts to connect and to belong, the ease with which human affections can be overwhelmed by those same elemental appetites which for Gordon Gekko are the engine of humanity’s evolutionary surge forward and upward.

We have noted how the bond of friendship between Alex, David and Juliet can only be maintained by ‘sacrificing’ any affection for anything and anyone beyond themselves. Outsiders are treated with open contempt or kept at a distance; the reluctance of the flatmates to answer the telephone or open the door gives even their finely-appointed flat a claustrophobic feel. When they decide to dismember and bury Hugo’s corpse and to stash the money, the tenuous dynamic of this Freund-Feind (friend or foe) arrangement is upset. The cynical hostility, which until then had barricaded their friendship from the outside world, is now unleashed among themselves. Juliet’s inability to decide whether she loves David or Alex instances the new confusion and is the prelude to a complete meltdown of trust. There is, in the end, no way that the money is going to be split three ways. Is each one looking out for him- or herself, or is it two against one? If so, which two?

A ‘sacrificial’ resolution – one which involves victims – becomes inevitable. Lest this term seem fanciful or overly ritualistic, it is worth noting that at one point Alex is watching a film on television: the film is The Wicker Man, the cult horror movie in which a hapless police officer (played by Edward Woodward) is burnt as a human sacrifice, as the climax of a pagan ritual.

Greed (or cupidity, or avarice) is deadly, not simply because it leads to actual death among the friends who are consumed by it, but because it is corrosive of all human relationships: the corresponding virtue is charity. It has perhaps taken a major economic recession to remind us of this: the Occupy protests against the excesses of financiers, most iconically the camp outside St Paul’s Cathedral, resulted from a widespread recognition of this, as well as a rejection of the Gekko ‘doctrine’. Evolution, surely, consists in the curbing and negotiating of appetites, not simply allowing them untrammelled license. Better still, those same appetites await transformation, as implied in Philip Larkin’s poem, ‘Church Going’, where the church is described as:

A serious house on serious earth …

In whose blent air all our compulsions meet,

Are recognized, and robed as destinies.

This is important: rejecting the Gekko ‘creed’ need not and should not imply a complete suspicion or renunciation of desire as such, even though some traditions of asceticism seem to demand this. Gekko offers a hint of truth: he judges our appetites and drives to be life-affirming, indeed they are the stuff of life itself. ‘Our hearts are restless’ says Augustine, whose youthful tempestuous search for God makes this one huge understatement. Augustine only finds peace when he moves beyond a dualistic, Manichean disparagement of the human, and decides that the desiring heart is not evil, merely yearning for its proper object: ‘our hearts are restless, till they rest in Thee, O Lord’. Left to themselves, our appetites render us needy, fanatically grasping; centred on their true object, God, they are ‘recognized and robed as destinies.’

Greed is an odd sin to think about, because we can easily render it as merely a quantitative transgression – having two slices of chocolate cake is being ‘greedy’ – when what is at stake is our very modality of desiring, acquiring and possessing goods. By ‘modality’ I am referring to a choice: between grasping a good, or receiving it as a gift. Much contemporary theology converges on the ‘modality of the gift’, as exemplified in, for example, the French theologian, Jean-Luc Marion. In a classic but difficult work entitled God Without Being, Marion has a moving reading of the story of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15), in which he draws attention to the fact that the son’s request to his father, to ‘give me my share of the inheritance now’ is, very precisely, a request for the two them to no longer be in relation. Children, after all, normally receive their inheritance on the death of their parents; the son is saying, morally and legally, ‘Dad, I wish you were dead!’

The point is further dramatised when we realise that the New Testament word rendered here as ‘inheritance’ is the Greek ousia, meaning substance, or being. ‘Father, give me my identity, my being … but I want to have my existence independently of you, outside of any relationship with you’. And of course, when the son receives this ‘being’, it slips through his fingers.

Once again: who do we believe? Is greed (‘for lack of a better word’) good? Is it some kind of elemental life-force – an appetite for life, love, money, knowledge, recognition, ultimately for being itself – which must be cherished and given free expression, so that human evolution can continue onward and upward?

Or is this path an illusion, because the ‘being’ which is merely snatched in this way becomes unsubstantial in our hands, worthless like the suitcase of shredded newspaper which is substituted for the money at the climax of Shallow Grave? True wealth is only possible when it is received as gift and in relationship – something which each of the sons of Luke’s parable have to find out. Outside of the relationship in which they are ‘robed as destinies’, our appetites can lead only to destruction. From a biblical perspective, unrestrained pursuit of our appetites would make us thieves, like Satan, or like Adam and Eve; and because such grasping puts us into competitive hostility with one another, then sacrificial killing (Cain murdering Abel) is never far behind.

An important theological drama was played out on British television screens in late 2011. Most of us will remember, with varying degrees of affection, the notorious John Lewis commercial, which featured a young boy waiting impatiently for Christmas. To the plaintive strains of ‘Please Let Me Get What I Want’, we see him fidget and fret until Christmas morning when – to one’s delight or nausea – it is revealed that the lad has been champing at the bit all these weeks to give a present to his parents, rather than receive gifts himself.

The message, that it is far better to give than to receive, of course made for a highly profitable festive season for John Lewis. My own hypothesis is that the extraordinary success of this feel-good campaign might be understood as a reaction to the trauma of the summer’s events in Britain, when blind, naked greed rampaged through our streets. The sheer, implacable urgency of appropriative appetites, suddenly finding themselves with access to trainers and television sets without hindrance or apparent sanction, was shocking; it would nevertheless have been recognisable immediately to Augustine. The anthropological question which the riots put to us – ‘Is this what we are really like?’ – produced, four months later, an emphatic, feel-good response: no, we are not needy, grasping anthropoids; yes, we are still fundamentally capable of entering into the logic of gift and of giving, of a sacrifice of self rather than the victimisation of those who get in the way of our appetites.

And we are still, perhaps, capable of hearing the echo of another tale, of one who ‘did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself’ so that we, as his adopted brothers and sisters, could have life in its fullness.

Michael Kirwan SJ is Head of Theology at Heythrop College, University of London. He is the author of Discovering Girard (Cowley, 2005) and Political Theology (DLT, 2008).