As the Society of Jesus prepares to celebrate the feast of its founder on 31 July, Ron Darwen SJ explores two different portrayals of St Ignatius of Loyola, and describes how the Jesuits' first General continues to accompany them on their spiritual journeys, as they strive to follow his example.

On the 31st of July the Church celebrates the feast of St Ignatius of Loyola, one of the founding fathers of the Society of Jesus and its first Superior General. Earlier this year the Jesuits held a General Congregation, the 35th in their history, at which they elected Fr Adolfo Nicolás of the Japanese Province to replace the out-going and much loved Fr Peter-Hans Kolvenbach as their new General and latest successor to Ignatius.

After that election, the Congregation took some time to reflect about the role of the Society in today's world. The Congregation was trying to "rediscover its charism", "reaffirm its mission today" and examine "the governance needed for the service of its universal mission". What, I wonder, would Ignatius have made of their conclusions? Would he have felt at home in their discussions? And would he have been able to recognize “the Jesuit” they described?

Knowing the Mind of Ignatius

The answer to those questions depends on what you think he was like. And that is problematic, since the picture we have of Ignatius has changed significantly over the years. If you were to put that question to a Jesuit novice or to a member of the Christian Life Communities, likely as not they would describe a man who could “find God in all things”, who developed a way of following God’s will in everyday life, someone who used his imagination in his prayer and who liked nothing better than to converse with people about “the things of God”. But that is actually quite a contemporary view of the man and very far from the Ignatius I was introduced to when I entered Jesuit life.

Of course it is not at all surprising that each generation has a different slant on an admittedly complex character. To some extent we probably all see in Ignatius things that are important to us. But the founder’s character has, on occasion, been the victim of rather less innocent attempts to mould Jesuit identity. A few years ago, the late Irish Jesuit, Joe Veale wrote of the interpretations of Ignatius' life. Most of our popular images, he points out, go back to the first official biographies, written towards the end of the sixteenth century by Pedro de Ribadeneira and Gian Pietro Maffei. But there is a source which pre-dates them, an Autobiography consisting of the personal reminiscences of Ignatius dictated to, and written up by, an early Jesuit companion, Gonsalves da Camara. This narrative has to be the seminal portrayal of the personality of Ignatius.

Not everyone appreciated the picture of Ignatius which emerged from da Camara’s pen. In 1567, Francis Borgia, the Jesuits’ third General, recalled all the copies of the Autobiography so as to clear the way for Ribadeneira's "true" account of the founder’s life:

The Provincials are to make a good job of gathering in what Fr Louis Gonsalves [da Camara] wrote, or any other writing about the life of our Father, and they are to keep them and not permit them to be read or to be circulated among our people or others. For being an imperfect thing, it is not appropriate that it cause problems.

The instruction seems to have worked. Some months later Ribadeneira, answering a query from Ignatius’ friend and companion Jerome Nadal, comments that:

the gathering in of Fr Louis Gonsalves writings about the life of our Father did not originate with me, but from the fathers who remembered our Father. And it seemed a good idea to his paternity so that when what is written gets published it should not appear that there be divergence or contradiction or that the work not have as much authority as what was written almost from the mouth of the Father. This although very faithful in substance is short on the details of some things and in relating of times by then well past, his memory was failing him owing to his old age.

The Autobiography duly fell into oblivion. It is true that the Bollandists included a Latin translation in the 1731 Acta Sanctorum but the original Spanish remained unedited until the first edition of Ignatian biographica in 1904. However you read these goings-on, two things are for sure. First, the image of the founder mattered then, just as it does now. Second, Ignatius’ own self-understanding, as it was handed on to his spiritual sons in the Autobiography, was to be marginalised and effectively lost for centuries to the great impoverishment of the Society at large and its spirituality in particular.

Ignatius, Man of Action

So how did that crucial depiction of Ignatius as it appears in the work of Ribadeneira impact on the identity and mission of Jesuits? Like any historian, Ribadeneira had his own preoccupations, many of them dictated by the age and culture in which he lived. His biography of Ignatius appeared in the aftermath of the Council of Trent, and so is marked decisively by the ethos of the Counter-Reformation and its aggressive stance towards Protestantism. It is not surprising to find that Ribadeneira’s Ignatius is a great soldier saint. Spinning such an image hardly required a huge amount of invention. There was already much in the life of Ignatius to suggest a penchant for swash-buckling derring-do. His upbringing had been that of a minor aristocrat and his almost exaggerated sense of chivalry got him into hot water in Pamplona, famously resulting in his leg being shattered by an enemy cannon-ball. Was such a man not destined to take his place among the great reformers of the Church’s history? Certainly, such a re-telling of his life was to forge a powerful myth, that of a kind of clerical Errol Flynn, and generations of young Jesuits would be inspired (and, one imagines, occasionally brow-beaten) by fervorinos from their novice masters exhorting them to imitate the heroic knight. Joe Veale, remarks:

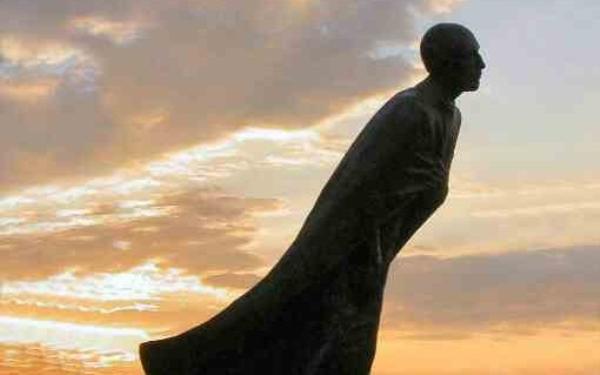

The St Ignatius we inherited from the 19th Century was stern, more than a little inhuman, a soldier, militant, militaristic, a martinet expecting prompt unquestioning execution, the proposer of blind obedience, not greatly given to feeling or affection, rational, a man of ruthless will-power, hard in endurance, of a sensibility (if it were there at all) under stern control, heroic. That was when he was not a superhuman, Olympian figure, just this side of apotheosis, remote among baroque clouds and shafts of light and gambolling cherubs.

This Ignatius, who survives in the popular imagination of many Catholics today for whom the Jesuits are something like a spiritual SAS, the Pope’s shock troops, was pre-eminently a doer. And surprising as it may seem, I have to admit that it was this Ignatius that led me to enter the Jesuit Novitiate in Roehampton 1949. I had been brought up in Preston in the heart of Catholic Lancashire, a descendant of St Edmund Arrowsmith, and a member of the Gerard family – John being the only Jesuit to have escaped from the Tower of London. The blood of the martyrs flowed through my veins, and I was privileged to be accepted as a Jesuit novice. As a descendant of one of the forty martyrs, I thought I would give my life to the conversion of England, teaching for the rest of my days in one of "our schools" with Ignatius as guide and mentor.

Ignatius, Mystical Master

That said, the Ignatius I have come to know since then tells a different story and that shift echoes a general change in the way Jesuits understand themselves. It is above all the rediscovery of the Autobiography which has put the Society back in touch with Ignatius, the man of prayer, someone with an extraordinary capacity for sensitivity to his interior life, keenly aware of the motions of the spirits, good and bad, able to taste the sweetness of the Trinity even in the most challenging of environments, and gifted with a visionary insight which created and responded to a wealth of apostolic opportunities aimed at helping others to experience Jesus Christ as he had. Joe Veale again:

There we see a man of feeling often given to tears; a spirit of soaring imagination; a dreamer with sensitive self awareness, attentive to the subtle movements of his sensibility; a man of strong affectivity with a gift for friendship and affection; a companionable person.

It has been one of the great privileges of my Jesuit life, straddling the Vatican Council and enjoying the great rediscovery of Jesuit identity which followed it, to see just what a potent agent of ecclesial transformation this Ignatius could be. As a novice in the old days, I had made the Spiritual Exercises along with thirty companions. The novice master would give us five talks a day and for me the experience was dominated by the vision of a large red notebook in which I wrote down every word that came from his mouth, hardly a transformative process! But years later I was to make the Spiritual Exercises the way Ignatius himself intended them to be given: “one to one”. Having a guide or director to accompany you on a daily basis, helping you to articulate, explain and discern your prayer is quite a different prospect, and it was thus that I learned what Ignatius was actually trying to do for people: introduce them to how God speaks directly to the heart.

Ignatius as mystic is probably the Ignatius most members of the Society know best these days. The last thirty years have seen a tremendous growth in the giving of his Spiritual Exercises and now spirituality is something that practically every Jesuit can talk about in some form or other. Although not always adept in the arts of “communal discernment”, Jesuits know deep down that Ignatius’ true genius lay in the way he handed his destiny over to those mysterious but profound experiences in which he knew God to be calling him. It is a daunting challenge to follow in those footsteps, in some ways rather more testing than trying to keep up with the militant Ignatius of the Counter Reformation in his camouflage and flak-jacket. Brian O'Leary observes:

Ignatius the mystic has replaced Ignatius the soldier saint. For reasons that are part historically well grounded, and in part politically correct, references to Ignatius' soldierly background and mentality are very rare nowadays. Everything that Ignatius did and wrote is traced back to his mystical experiences on Manresa, at La Storta and in Rome. Hence the strong interest in the Autobiography and the Spiritual Journal . As always there is truth in both, that he was both a doer and a mystic. The challenge of his life to present day Jesuits has been to hold together a spirituality that does justice to both. Today's Jesuit should have a foot in both camps.

Having a foot in both camps is no mean feat (if you’ll pardon the pun). In fact, if there is a new challenge emerging for Jesuits in the early years of this new century it seems to be precisely that of deepening the integration of prayer and action. That, in any case, is, my reading of the latest General Congregation.

General Congregation 35

No doubt had Ignatius paid an impromptu visit to the Congregation as it sat in Rome, he would have identified strongly with this group of priests and brothers, active in the life of the Church, as they discussed their mission, trying to work out what they ought to be doing. Ignatius the doer would have felt very much at home. But I think he would also have been keen to point out that doing was not enough. He would want them to say something about the subtle and tricky business of identity, about deep motivation and drive, about what makes the Jesuit heart beat that little bit faster, about what Hopkins calls the “dearest, freshness, deep-down things”.

Perusing the decrees, I’ve got a feeling his spirit was there. The first document responds to just those questions: what are Jesuits all about in today's world? How do they see themselves in the Church? What makes them tick? And so it takes up the question of fundamental Jesuit identity and offers a poetic image in its title, "A fire that kindles other fires". Jim Corkery, an Irish Jesuit who helped to write this Decree, wrote recently:

At a time when people frequently admire what Jesuits do, although without knowing why we do it, it is important to indicate that none of our Jesuit schools and universities, nor any of our pastoral, social or spirituality centres, not even the Jesuit Refugee Service is understandable unless the ‘polarity’ of being with Christ and at the same time being active in the world is expressed and made visible in them. Living ‘polarities’ is central to Jesuit identity. [...] Ideally Jesuits live out of an awesome grace that tilts us towards seeing the world with the eyes of Christ, loving it with his heart and serving it with his compassion. It is not a matter of meeting needs, doing good, acting justly alone. Nor is it a matter of having faith, praying, living contemplatively, alone. Rather it is a matter of doing both together.

Ignatius, I cannot help but feel, would have been enchanted to read those words. They seem to sum up for me who he really was: mystic and militant, or, as Nadal put it: a contemplative in action. A hundred years after Ignatius's death, a Belgian Jesuit, suggesting an epitaph for his grave stone, grappled with the same notion. It is in Latin and not easy to translate, but I will have a go:

Non coerceri a maximo, contineri tamen a minimo, divinum est.

(Not to be daunted or held back by the greatest challenge and yet to be concerned with the nitty-gritty, that is the path to holiness.)

Ignatius had an uncanny feel for the big picture. He could see the wood for the trees and at the same time realised the importance of the trees. William Blake's words could well have come from Ignatius: "if you would do good, you must do it in minute particulars". Ignatius the man of vision, the man of order, could do both at once. That is what modern Jesuits still try to do.

Ron Darwen SJ joined the Jesuits in 1949 and has been Novice Master, Tertian Master and is now based in Birmingham where he is involved in giving the Spiritual Exercises.