The growing number of immigrants crossing the Mexican border are changing the way that the Catholic faith is lived and practised in the United States. Despite the challenges they may present to and face in civil society, their vibrant presence is a blessing for the church, argues Nathan Stone SJ.

Although Catholicism is actually the largest unified religious denomination in the United States, counting nearly a third of US residents among her faithful, she still perceives herself as a marginalized and misunderstood people. In many ways, she is. Most Americans, even Catholic Americans, feel threatened by Catholic intensity, by the sense of community, and by sacramental devotion, which, for Puritans, smacks of witchcraft. Americans get nervous about being in touch with transcendent reality. It might change their plans, or their illusion of controlling the world.

Most Americans are afraid of a Church that might come out of the churches, into the streets. We have separation of Church and State. We have freedom of religion, but with the condition that one never see or hear about it. Most people go to some church, but no reference to religion may ever be heard in public schools. In 1984, actor Martin Sheen was arrested along with others, for peaceful protest against the US funding of right-wing forces in the Central American wars. A heckler shouted at him, as he was carted away, Are you a communist? His retort was, Much worse. I’m a Catholic. What happens now, with the arrival of Mexican immigrant Catholics, for whom prayer, as often as not, is a procession through the city streets?

Protestantism, and more exactly Calvinist Puritanism, is the bedrock on which the United States of America was founded. That is her ideological foundation, even among those who are agnostics, or assimilated Catholics, today. The first colonies were generally Protestant. Some were business ventures, like Jamestown, in Virginia. Others were overtly religious movements, like the Mayflower pilgrims, of Massachusetts. The marriage of business and Puritanism has begotten this new nation. One notes strains of Freemasonry, sometimes, a balance to evangelical fundamentalism. Catholic, on the other hand, was never part of the equation.

Demographically, if you add the members of all the Protestant denominations, they are far more numerous. Protestantism, you might say, is an individualist’s religion, and it tends to subdivide, but it retains certain characteristics. From Luther, we get radical individualism. In liberal discourse, this becomes the right to do whatever one feels like, and demand that the government pay for it. In ethics, it becomes the tyranny of an untrained conscience – in Catholic parlance, ethical relativism.

From Calvin, we get double predestination: a sharp divide between the saved and the lost, an impenetrable border fence separating them. My Baptist grandmother lived within shouting distance of the Mexican border most of her life, and never learned a word of Spanish. Why would she learn the language of the lost people? If God had wanted to save them, he would have made them white and English-speaking, right?

It’s interesting to note the prominent place purgatory holds on the American Catholic catechetical horizon. In other places, it might be a quaint metaphor for God’s solid and never-ending mercy that transcends even death. This is a right understanding, and we should probably leave it at that. For American Catholics, though, it’s a big deal, because it’s something that makes us different. Luther sends you straight to heaven or hell, at the hour of your death. So, American Catholics spend hours praying for their poor souls in Purgatory, her silent dissent.

Some take that to mean that the Catholic God is punishing. But the point is that the Catholic God is forgiving. He always finds a way for you to come back to Him. The American Calvinist God does not forgive, or so it seems. He closes the door on sinners, once and for all. This explains the high prison population, and the persistence of the death penalty in a world that has, for the most part, given that up. Civil society is permissive, but unforgiving. Catholicism is demanding, but willing to give a second chance.

Calvinism can then be used to justify a whole range of social sins, from racial discrimination to the gratuitous invasion of foreign lands. It also rationalizes economic gain as a gift from God. The chosen people will be blessed with lots of money, even if it means they steal it from the not-chosen, or exploit their labour. The gospel of prosperity drives a nation, and puts the power of the purse where Calvin would say it belongs, among the saved.

Freemasons are few and far between, among them George Washington, and Benjamin Franklin. They tend to be of the northern European, and thus, more tolerant, variety. Aside from their usual culture of hubris, they did also leave a Constitution allowing for no established Church, and freedom of religious practice. Through this loophole in the Puritan network, the Catholic immigrants have come.

With many others, notably Eastern European Jews, they came to Ellis Island, in New York. The Catholics were Polish, Italian and Irish, all looking for a better way of life, in a New World. They were distrusted and segregated, but by banding together (a Catholic thing) they managed to get by. The parish, and often its adjoining school and convent, became the cultural centre, and source of connection with tradition, family and the Old World. Being Catholic meant being different. It also meant belonging to a family where you had a place at the table.

Enter the Mexican immigrant. Always an important presence, today the undocumented are estimated to be over twelve million. These are the guys who fly under the radar, in order to tend the gardens, wash the dishes, build the homes, prepare the food, and attend Sunday mass at the local Catholic parish, if they have one in Spanish.

Studies have shown that, in the US, one in every four Catholics raised in the faith has left it by adulthood. In spite of that, the Church continues to grow, especially in areas where the immigrants are numerous. Fifty percent of Dallas Catholics today are Spanish-speakers. Fort Worth only trails a bit behind, at forty-five.

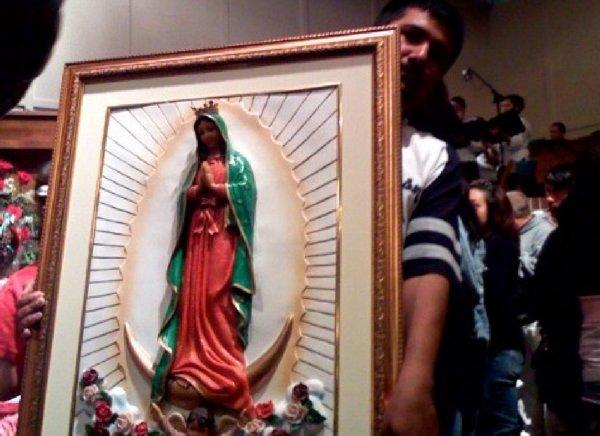

They come from Mexico and Central America, pilgrims through the desert, bringing traditional food, dance, devotion, language, colour, smell and, most important, Our Lady of Guadalupe. Here they are, trying to graft themselves onto an American Church, where the emphasis is on rules, catechism, and liturgical propriety.

The American Church, in her efforts to become mainstream, has adopted Calvinist attitudes about right and wrong, saved and lost. She therefore has difficulty processing the irregular migratory status of the new faithful, and the spontaneous and colourful nature of their devotion.

Some of the most open-minded white people find the pageantry of Latin American religion to be at least, interesting. Evangelical Protestants often regard theatre as sinful, along with dancing and alcohol. When public schools and churches wanted to have a presentation, it consisted of costumes and some wooden walking out and making pronouncements of historical facts. This was called a pageant.

Latin Americans don’t do pageants, the do la pasión. They act out what is in their heart. There is no place for them to stay, so they are Mary and Joseph in Bethlehem, searching for a place to take them in. That is Posadas. The matachines dance a devotion that won’t come out in words. One man said, it was as if Jesus himself were lifted up on the cross before my eyes. This is as real as it gets, an outpouring of uncontrollable passion.

The immigrant faithful of today relive the humbling of the haughty and the exalting of the lowly in the story of Juan Diego and Our Lady of Guadalupe. At a recent presentation of the apariciones, the actors wept during the final scene, because they were seeing her again. She is always with them, sharing their joys and sorrows, as a good mother would, as Holy Mother Church is called to do.

The Church is becoming colourful and tasty. In some places, the balance has already tipped. What often began as outreach to the Mexican community, has become all there is. The Dallas area traditionally had a very small Mexican American community, part of an already minority Catholic population. The Church has grown from less than 200,000, twenty-five years ago, to over a million today. Half of those are immigrant Mexicans and Central Americans. Most are of childbearing age. Most English-speakers from the post war “baby boom” are becoming elderly.

Predictions are that, by 2040, up to 80% of Catholics in this area will be of Latin American ancestry. Of course, by then, they will be second and third generation US citizens, if the authorities don’t deport them first, or deport their parents and leave them in foster care. Will they still dance for our Lady of Guadalupe? Good question.

The story is very different in San Antonio. This city was there long before Texas was Texas. Over 85% of the Church there is of Mexican descent, colourful, and devotional, and at the same time, rule-oriented and catechetical. But they speak English, they are US citizens, they shop at Walmart, they vote Republican and they serve in the military. And, they have done so for many decades.

At the Encuentro Nacional de Pastoral Juvenil Hispana, a national meeting of Catholic Hispanic youth at the University of Notre Dame in 2006, there were young Hispanics from all over the country. Dallas and Fort Worth sent Spanish-speaking delegations. Two thirds of the three thousand delegates were immigrant, and non-English-speaking. Like Dallas, there are many places with a very recent immigrant presence: North Carolina, Chicago, and the Midwest. But San Antonio sent an English-only delegation. That is their reality. The same is true of many parts of the Southwest, New York and Florida.

One would think that people with Latin American ancestors might be the most sensitive and welcoming to the immigrant, yet it is not always so. The Mexican American, in Texas, New Mexico and California, often resents the Mexican national. They say, those people are ruining it for us. And, it’s true, in a way. If your name is Juan Perez, nowadays, you have to prove that you are not a foreigner if you are stopped for a traffic violation, or if you want to apply for a job. John Smith has nothing to prove.

For San Antonio Catholics, the struggle, over the years, has been parallel to the Civil Rights Movement: how to claim their inalienable rights as citizens, alongside African-American brothers. For the immigrant there is no citizenship and, therefore, no rights.

The American economydepends, more and more, on foreign labour. When the jobs themselves can be outsourced, they are. Bicycles are assembled in China, and telephone services are answered in India. But it’s hard to have the roof put on your house in Michoacán, or your dishes washed in San Salvador. So, here they are. The US needs them, and yet, asks them, please be invisible.

Xenophobia is, of course, on the rise since 9/11, and the brownness of the Mexicans and Central Americans is often associated with the brownness of the Saudis who made that attack. Some have even imagined terrorist cells walking across the southern border disguised as Mexicans looking for work. Far-fetched, but for Americans who don’t travel and are afraid, it’s plausible. So, Manuel the brick-layer must pay the price.

The US Bishops have called the Church to welcome the stranger among us, with all the Biblical richness that calling evokes. This is an eye-opener, and a challenge. Leviticus calls on the people of God to remember when they lived as foreigners in the land of Egypt. There are no Catholic families who were not, at some point, first generation immigrants. And yet, it is easy to forget, and to run the Mexicans out because they don’t have the same notion of rules and times and straight lines.

Among English-speakers, the Church is experiencing a resurgence of pre-Council piety. This is, in part, the legacy of the late Pope John Paul II, and it is especially strong among young people, who never knew incense or Latin. It is ethically demanding, politically active, and liturgically old-fashioned. And it’s very fair-skinned. It’s good to see the new fervour, and some are discovering a real sense of the sacred, which they have never known. This could be complimented by Hispanic religiosity, but it is not a segment of the Church that tends to be particularly welcoming to strangers.

Some, obsessed with Biblical righteousness[1], criticize the immigrant for not queuing up to get his visa before crossing the River. With over twelve million waiting, and only 66,000 visas available for labourers each year, the queue is 185 years long.

By Baptism, the undocumented immigrant has a canonical right to come to Church. Natural law obliges him to feed his family. Economic law requires him to take his supply of labour to where the demand is. Yet, civil law forbids him to be on the street. That is our contradiction. But we know where our priorities are.

An attempt at immigration reform failed in the Congress in 2007. It was well-intentioned, perhaps, but it had a fatal flaw. It dealt mostly with the path to citizenship. It essentially said, You can stay here if you learn English and be like us. In some way, that means, be Protestant, individualist, and Puritan. Yet most workers here have homes on the other side, and would go back and forth across the border, as they did for decades, if allowed to do so. That has become very dangerous now.

The border,with its growing fence,now divides families. Most of the immigrants are young men, many of them unmarried. Their mothers, sisters, wives and girlfriends are back home. This is hard for men from a very family-oriented culture. The Church is their family here, a link to what they know. I’ve never seen so many young men at Sunday mass, making retreats, seeking the sacraments. The Lord is clearly their strength and their salvation.

Some say that the wave of Latin American immigrants is just like earlier waves of immigrants from Europe. There are similarities and differences. The US has a border and a history with Mexico. The oldest generations of Mexican Americans were Spanish settlers in Texas, New Mexico and Colorado. They stayed where they were and, in 1848, the border moved south on them. In the 1920s and 30s, many Mexicans fled the chaotic social upheavals at home, seeking asylum in the US.

During the Second World War, workers were invited to come, as part of the Bracero program. Crossing the border to work is a tradition started by the US government. The American labour force was in military service, so Mexicans were needed for food production and manufacture.

After the war, they were invited to leave. But the law of supply and demand still requires them to come. Anti-immigrant feeling runs high. Since most immigrants from south of the border are Catholic, at least when they arrive, anti-immigrant feeling reinforces a pre-existent anti-Catholic feeling.

In some places, the Catholic Church has done a wonderful job of welcoming the outsiders. In other places, there is tension. Local rules and procedures are often used to marginalize the newcomer. Cultural misunderstandings are often taken as deep-seated doctrinal errors. Other times, the grace of God wins out, even if only on the invisible underside, where the Risen Lord and the ragged people tend to gather.

There is the Houston Catholic Worker House, called Casa Juan Diego, where the recently arrived are taken in for their first few days. The neighbours complain about the Catholics bringing in droves of Mexicans. But Dorothy Day was a believer in the Benedictine tradition: a door must be always open to the wayfarer.

Inner city parishes have become Little Mexico. The rules change, the smells change, the activities change, and the English-speaker can feel like an outsider. Requirements such as registration, filling in forms and paying fees – all sacred doings in the American Church – are often put off for later.

Other mega-parishes in wealthy suburbs have taken on the growing Latin population as their on site mission, with varying degrees of success. The danger is perceived as a formation of parallel churches: one where rules and catechism win the day, the other where the passion play and Guadalupe are most important. Each has what the other lacks, if we could only see it.

One local parish has a new building that can hold fifteen hundred faithful for one mass. They have three English masses and three Spanish masses every Sunday. All are full. The collection at the three English masses is eight times as high as the collection at the Spanish masses. This, of course, reflects an economic reality. As a percentage of income, that’s not too far off the mark. But it causes bad feeling. Another statistic is telling. Every week there are baptisms. Two or three children will be brought to the English service, and twenty-five will come for the Spanish.

This might mean that the American Church will grow in numbers, and yet become poorer. Not that that would necessarily be a bad thing. It would make the Church in the US more like the Church in the rest of the world. And the gospel tells us that the poor are happier than the rich. This could be a great favour.

The best part of it all is that this is not something anyone can control. The Holy Spirit has got us into this, and will see to the outcome. That might be the greatest learning opportunity for the American Church. She wants to control everything, to try and stay among those few predestined for Calvinist salvation. The Latin American attitude is that God will take care of it. Some days will be good, and some bad, but all will be God’s. We might finally be saved from our cultural Calvinism, after all.

Holy Spirit, we thank you for the missionaries you have sent us.

Nathan Stone SJ is a native Texan, 1979 graduate of the University of Notre Dame, and 1987 MA from the University of Texas, with a concentration in rhetoric. As a teaching volunteer in Chile, and inspired by the Ignatian model, he became a Jesuit in 1992. A member of the Chilean province, he studied Theology at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, and he was ordained to the priesthood there in 2000. He has worked in education, youth and social action ministry in Santiago, Antofagasta and Montevideo. His most recent publication is an article called, Thoughts on Youth and the Ignatian Method, Spiritual Exercises for Life Choices, (Review of Ignatian Spirituality, 117, CIS, Rome, January, 2008). He is currently in Texas, at Montserrat Retreat House, working with the migrant Hispanic population there. He will return to Antofagasta in August.