Twenty years ago today in El Salvador, six Jesuits, together with two women who were sharing their university residence, were murdered by the Salvadoran military. Dean Brackley SJ tells the story of the Jesuit martyrs, who will today be bestowed with El Salvador’s highest honour. What can we learn from these teachers who stood up against an unjust regime and remained firm in their commitment to serving the truth?

Our colleagues at Pray as you go have prepared a special reflection for the 25th anniversary of the El Salvador martyrs. Listen >>

Sometimes, late in the game, justice is done and the truth served. Just two weeks ago, the President of El Salvador, Mauricio Funes, announced that on 16 November his government would bestow its highest honour, the Order of José Matías Delgado, posthumously, on the six Jesuits who were murdered twenty years ago on that same date.

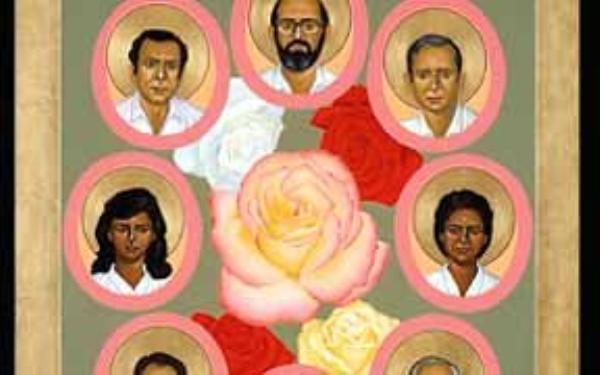

In the early hours of 16 November 1989, US-trained commandos of the Salvadoran armed forces entered the campus of the Jesuits’ university, the Universidad Centroamericana (UCA), and brutally murdered the six Jesuits, together with two women who were sleeping in a parlour attached to their residence. The Jesuits were: the university rector Ignacio Ellacuría, 59, an internationally known philosopher; Segundo Montes, 56, head of the Sociology Department and the UCA’s human rights institute; Ignacio Martín-Baró, 44, the pioneering social psychologist who headed the Psychology Department and the polling institute; theology professors Juan Ramón Moreno, 56, and Armando López, 53; and Joaquín López y López, 71, founding head of the Fe y Alegría network of schools for the poor. Joaquín was the only native Salvadoran, the others having arrived long before from Spain as young seminarians. Julia Elba Ramos, the wife of a caretaker at the UCA, and their daughter Celina, 16, were eliminated to ensure that there would be no witnesses. Ironically, the women had sought refuge from the noise of gunfire near their cottage on the edge of the campus. Julia Elba cooked for the Jesuit seminarians living near the UCA.

This was one crime in a long series that included the martyrdom of Rutilio Grande SJ in 1977, and those of Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero and the four US missionaries: Jean Donovan, Ursuline sister Dorothy Kazel and Maryknoll sisters Ita Ford and Maura Clarke, in 1980. They all mixed their blood with that of tens of thousands of lesser-known civilian victims of El Salvador’s civil war of 1981 to 1992, which moved the world with its extremes of cruelty and of heroic generosity.

The killings at the UCA took place during a major guerrilla offensive that began on Saturday 11 November 1989. Ellacuría returned to El Salvador from Spain the following Monday. A few hours after he arrived at the UCA, a commando unit of the Atlacatl Battalion searched the Jesuit residence. It was reconnaissance. Two days later the High Command of the armed forces gathered at their headquarters a kilometre away from the UCA. In fear of losing the capital city, and perhaps the war, they decided to rocket the poor communities where the guerrillas were now entrenched and to act on a long hit list of civilians critical of the government and the armed forces. Almost all on this death-list, including labour leaders, opposition politicians and some clergy, had gone into hiding once the offensive began. The six Jesuits did not.

Even after the Monday search, Ellacuría prevailed on his brothers to remain at their UCA residence. They had nothing to hide, they had done nothing wrong; nor were they members of the FMLN (Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front) guerrilla movement. The accusations – that the UCA stored weapons and trained guerrillas – were patently false. And, with the campus surrounded by soldiers protecting the military installations close by, any harm done to them would be blamed on the army. It was a logical argument; yet, as frequently happens in wartime, unreason prevailed. Shortly after the Wednesday night meeting of the High Command, the Atlacatl unit returned to the UCA to murder the Jesuits and the two women. The soldiers simulated a military confrontation, leaving over 200 spent cartridges, to make it look like the Jesuits had fallen in combat.

With fighting raging around the capital, the military had hoped to pin the murders on the guerrillas. When that quickly proved impossible, the Salvadoran and US governments collaborated in a cover-up to shield the Salvadoran High Command. The government offered up nine soldiers who had participated in the operation. Thanks to enormous international pressure, all but one, who fled, eventually went on trial. Two were convicted in 1991 but were later released when the government pardoned itself (and the FMLN) for all war crimes. To this day the top officers have never been formally accused, let alone held accountable.

So, President Mauricio Funes’s decision to bestow the highest state honour on the fallen Jesuits begins to right an historic wrong. Funes was elected as the candidate of the FMLN, now a political party. His election in March 2009, following twenty years of rule by the right-wing party ARENA (Nationalist Republican Alliance), wrested political power from the control of El Salvador’s all-powerful economic oligarchy for the first time. The new centre-left government inherited a bankrupt state, an abysmal economic crisis and rampant violent crime. While it seeks to carry out reforms, it can do little to put food on the table or generate jobs. However, recognising the Jesuit martyrs is a powerful symbolic gesture that generates hope. It cracks the thick wall of impunity that ARENA governments had erected to shield themselves and the armed forces from accountability for the deaths of legions of civilian victims of state terror during the war. Funes said he considered honouring the fallen Jesuits as ‘a public act of amends, that is, of moral compensation, for the errors which the Salvadoran state committed in the past.’

As early as the 1990s, the UCA massacre became the crime that would not go away. Thanks to international pressure, including a US Congressional Task Force, we learned who the real killers were. Outraged US citizens, especially Catholics, pressured their government to cut off the military aid that was indispensable for the conduct of the war. By then, it was becoming more difficult to justify the war as a defence against the international Communist threat. The massacre at the UCA took place at exactly the time that Berliners began knocking down their famous iron curtain wall. In El Salvador, the scandal generated by the murders helped to speed up the peace negotiations and later, by discrediting the Salvadoran military, to consolidate the peace.

Like many others, the UCA martyrs were killed for the way they lived, that is, for how they expressed their faith in love. They stood for a new kind of university, a new kind of society, a ‘new’ church. Together with their lay colleagues, they wrestled with the ambiguities of their university in a country where only a tiny minority finished elementary school and still fewer could meet the required academic standards to enter university and to pay the tuition fees. The Jesuits and their colleagues concluded that they could not limit their mission to teaching and innocuous research. Yes, they did steeply scale tuition charges according to students’ family income. More importantly, they sought countless ways to unmask the lies that justified the pervasive injustice and the continuing violence, and they made constructive proposals for a just peace and a more humane social order. As a university of Christian inspiration, they felt compelled to serve the truth in this way. That is what got them killed.

For readers of a different time and place, we can translate the high standards the UCA set for itself as follows: first, the chief subject of study has to be reality itself. The ‘literature’ of various fields is a means to understanding reality, above all the core issues of life-and-death, justice, and grace versus sin. Second, the university must practically engage with the suffering world it seeks to understand, to serve and to help transform. Third, it should take a principled stand on the crucial moral issues of the day – not just abortion, we might say today, but also war, lying in public and torture. To search for knowledge without this kind of commitment would not only unduly limit the university’s mission, it would reflect a failure to appreciate how bad things are, not only in places like Central America, but in places like the US and Europe as well. It would mean failing to overcome the distorted standard discourse which we take for common sense. It would mark a failure to address the prejudices and blind spots produced by our socialisation into the middle-class society to which most of us university people belong. And this means it would amount to a lack of academic rigour.

The UCA martyrs also stood for a different kind of society. Ellacuría, like the theologian Jon Sobrino who lived with him but was travelling at the time of the killings, was an eloquent advocate for what he called a ‘civilisation of work’ to replace ‘the prevailing civilisation of capital.’ With great prescience he foresaw that this would not be principally the work of governments but rather of civil society, whose different sectors have to organise and point the way to new social models, beyond both communist collectivism and capitalism. In this, Ellacuría believed, ‘the poor with spirit’ would play a privileged role.

Finally, the UCA martyrs stood for a Church of the poor (in the words of Pope John XXIII) which would serve as a vanguard of this new society, modelling equitable social relations and solidarity; a prophetic Church like the one that Archbishop Romero symbolises, which gives credible witness to the fullness of life that God promises.

The UCA martyrs knew they were risking their lives. But they understood that that was the price of being human in their time and place; that was the cost of following Christ. Twenty years later we give thanks for them, and many like them who inspire us to live up to the challenge of our own time.

In announcing that he would bestow the country’s highest honours on the fallen Jesuits, El Salvador’s first president from the political left said that they had distinguished themselves for outstanding service in education, human rights, combating poverty and inequality, and in working for peace and democracy. He added that he and many members of his Cabinet regard them as ‘eminent Salvadorans who rendered extraordinary service to the country.’

At the Presidential Palace today, 16 November, some of their relatives will join the Jesuits of El Salvador along with representatives of the poor communities that the martyred Jesuits served. In their stead, those present will receive this historic public recognition. It is fitting that campesinos, mothers and workers, representatives of the crucified peoples like Julia Elba and Celina, share in this tribute, which is all the more welcome for coming so late in the day.

Dean Brackley SJ is Professor of Theology and Ethics at the Catholic University in San Salvador.

Our colleagues at Pray as you go have prepared a special reflection for the 25th anniversary of the El Salvador martyrs. Listen >>