Pope Benedict has invited the Church to observe a Year of Faith – is the faith we celebrate linked integrally to a particular narrative and if so, must it be understood in isolation from other religions? If faith is a response to the Word of God, asks Michael Barnes SJ, can one religion have a unique claim to it, or can we talk about those with different beliefs as ‘people of faith’?

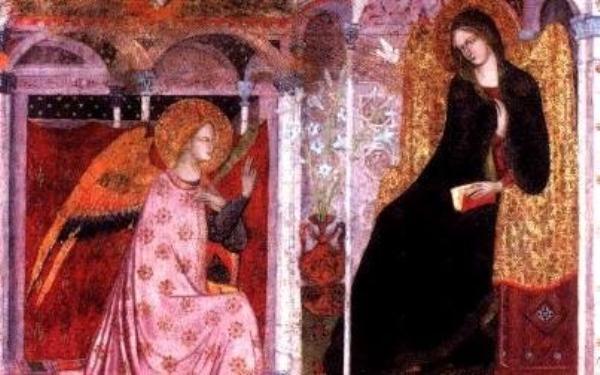

There can be few places which radiate the faith of Catholic Europe more powerfully than Assisi. On the plain below the medieval city stands the 16th century basilica of Our Lady of the Angels, built over the tiny chapel known as the Portiuncula where St Francis lived with his first companions and where he died in 1226. Grand architecture and the spirituality of poverty make for an incongruous juxtaposition, but a reminder, nonetheless, that culture carries faith across time. Above the altar is a painting of one of the greatest symbols of that continuity – the moment when Mary consents to God’s Word. In Ilario of Viterbo’s version of the Annunciation, dating from 1393, the angelic visitor kneels in respectful greeting while the virgin half turns away in confusion and alarm, one hand suspended in mid-air. Faith is portrayed not as meek subservience but as intense inter-personal encounter.

A recurrent feature of this scene in medieval painting shows Mary with a book. More often than not it is on a stand, but in the Portiuncula fresco, two fingers seem to be marking the passage she has been reading. Tradition has it that the book is the Bible; the passage is Isaiah 7:14, about the young woman conceiving a son. Another tradition suggests that Mary was reading the opening of the book of Genesis. She hears Gabriel’s ‘Ave’ reversing the name of Eve, ‘Eva’. A play upon words certainly, but more profoundly the story records an experience of revelation, an event within language requiring the active response of the listener. Luke tells us that she ‘considered in her mind what sort of greeting this might be’ (1:29). The Greek gives us the word ‘dialogue’: reflecting within herself, pondering back and forth the implications of the words. Today the term betrays connotations of well-reasoned negotiation; here it is rooted in prayer. In Christianity, faith is called forth by the Word of God which, entering deep into creation and the whole of human reality, makes possible the intimacy of colloquium, conversation, as between familiar friends and even lovers.

A contemplative space

Once spoken, the Word reverberates through human speech. Mary carries her story to her cousin Elizabeth. In response to Elizabeth’s words of joyful greeting, ‘Blessed is she who believed that the promise made her by the Lord would be fulfilled’, Mary utters her Magnificat, a prayer of praise and exultation, glorying in what God can accomplish in the meek and humble. As with other songs of praise in these opening chapters, the words spring up suddenly, as if from some unsuspected underground stream. For faith is not a sort of semi-gnostic intuition, a glimpse of the esoteric. It is already there in Mary’s attentive act of prayerful reading, just as it is there in Elizabeth’s life of hopeful prayer for the blessing of a child. Faith, more exactly, is that movement of grace which shapes all manner of human feelings, desires and expectations. The stories of Elizabeth and Zechariah, Mary and Joseph, Simeon and Anna – and indeed the story of the poverello of Assisi himself – are held together by God’s divine action interrupting both our prayerful routines and our periods of inattentive distraction by bringing to birth a new movement of the imagination.

Faith here is an attribute or virtue of persons and is perhaps best described as the willingness to follow the movements of God’s grace. As faith moves the fearful Mary and gives her courage to ponder within herself, what is opened up is a contemplative space for language, a space within which the promptings of the Spirit can be spoken.

This, of course, raises a question. The language we use, whether in praise of what God’s Word achieves or in prayerful pondering of its inner meaning, is very particular. Mary’s fingers stay on the Bible, marking a point of intersection, a moment in time. There is something timeless about Assisi but – paradoxically – that timelessness is carried down the ages in very culture-specific terms. Pictures of the Annunciation, from whatever age, are shot through with the language of the Old Testament, language which Luke reconfigures to express something of his conviction that God in Christ is bringing all things to a new fullness. Is the faith which responds to God’s Word – the faith of Mary and Elizabeth and Francis of Assisi – so tied to biblical concepts and symbols that it necessarily excludes all those who, however sincere and devout their religious practice, are not part of the community whose faith is founded on the Word revealed and made incarnate in Jesus Christ?

Faith as promise

Put like that, there might seem to be only one answer. If faith is not some pre-linguistic gnosis but is only ever expressed in the scripture-soaked language of a community, then those who do not repeat that language cannot participate in the truth to which it points. But that is precisely what we cannot say, for it risks reducing language to the outer form which carries some sort of ‘inner’ meaning. It sunders the content of faith from the action of the self-revealing God. While Christian faith certainly makes truth-claims which are not in any straightforward way to be subsumed into analogous claims made by other religious traditions, the Gospel is promise before it is message. The narrative structure which reflects the action of the Spirit is logically prior to the discourse which the Spirit inspires. While language can always be reduced to a series of coded responses, primarily it acts as a medium of inter-personal communication, a sign of what the Spirit of God is always bringing to birth among human beings as they contemplate the mystery of the Word.

This focus on the life of the Spirit who opens up the Church’s contemplative space may be considered one of the most important legacies of Dei Verbum, Vatican II’s great Constitution on Divine Revelation. Dei Verbum shifts attention away from the ‘what’ of revelation to the ‘who’, from the words which contain revelation to the God who, in communicating Godself, endows the lives of persons with a grace-filled meaning. In so doing the Constitution is not just responsible for a new theological synthesis of the sources of revelation but also serves as a meditation on the Church’s experience of being formed and transformed through the Word of God. What begins with the Annunciation as Mary responds to Gabriel’s words continues wherever and whenever the Church finds itself pondering and praising the Word of God. In principle this process of lived interpretation of the Mystery of Christ is unending. Conceived as a ‘dialogue of salvation’, to use Paul VI’s celebrated phrase, it is impossible to put any arbitrary limit on the extent of God’s offer of the self-communicating Word.

That crucial shift of theological focus does not lead to any straightforward answer to our question. To repeat the earlier point, faith is carried by culture – and culture like language is always particular. But it does suggest a way forward, one which would resonate with the missionary vision of St Francis of Assisi himself.

At the height of the Fifth Crusade, in 1219, after the battle of Damietta in which some five thousand Christians had been killed, Francis crossed the lines separating the armies and visited the Sultan al-Malik al-Kamil. An overly romantic interpretation of the episode sees it as a model for interreligious dialogue. The truth is a little different, but no less significant. Francis presented himself as a messenger from God and spoke with no doubts about the truth of his Christian faith; his intention was to convert the Sultan to Christianity. In that he failed but the Sultan was clearly impressed by the gentleness of his manner and the zeal of his words. They conversed together about faith and peace. And when Francis returned home, he proposed that his friars commit themselves to living peaceably among Muslims – a radical move at a time when the only conceivable meetings between Muslims and Christians were on the battlefield.

Maybe that was the origin of his admirable sentiment: ‘preach always and sometimes use words’. Maybe too his experience of pondering back and forth in the wake of an unexpected outcome taught him that the Spirit both creates the contemplative space for language and disturbs those rather more comfortable spaces we construct for our security. Faith may very often seek for and expect to find a personal equilibrium; the fingers stay well and truly anchored in the pages of the book, for that is where we feel at home. But life in the middle of words is never straightforward. It is not that words themselves are inherently unstable, an ever-shifting set of signifiers, but that the process of speaking and listening, reading and studying, praying and pondering, opens up new possibilities and new configurations. All of this is involved in the process of dialogue – which, in the light of Dei Verbum’s personalist account of revelation, entails not the trading of propositions from which some negotiated outcome becomes possible but the much more risky encounter with the Word of God revealed in all manner of inter-personal meetings and conversations.

Faith and hope

Catholic Christians are apt to speak about ‘the faith’ as if it is a prized talisman, the badge of honour of the tribe, something to be set against the belief systems which belong to ‘other religions’. Clearly what Christians believe is not the same as what others believe. The strongly theistic narrative unfolded in the Gospels and the austere anthropocentric ethical and meditative practices of ancient Buddhism inhabit very different cultural and linguistic spaces. The narrative of Jesus’s passion and the story of Imam Hussein’s death at the massacre of Karbala are not parallel versions of some grand mythology. And the lines of Hindu avatars set around the mandir are not to be confused with the statues of Catholic saints. The work of comparison throws up all sorts of interesting points of convergence, but different religions – or ‘faiths’ - are sometimes very different indeed.

It does not follow, however, that, as human beings searching for a sense of significance and value in their lives, Christians and Buddhists and Muslims and Hindus cannot talk to each other and share profound insights about the nature of human flourishing. They can and they do. They may read the world differently – but they do read. That is what makes it entirely appropriate to call them ‘people of faith’ – not because they all share in some common religious language but because lives which have taken the risk to move into the contemplative space where language moves and challenges can be described as genuinely faithful. To live in confidence and hope of a fullness which is beyond human power to command is to hover, however uncertainly, around that realm of living and loving that properly belongs to the Spirit.

In Advent thoughts turn naturally to an account of faith inseparable from hope. It is not that the one anchors us securely in sustaining memories of the past while the other enables us to look forward with confidence to an uncertain future. Rather, united in the third great theological virtue of love, they allow us fully to enter into the mystery of God’s self-revealing Word, indeed God’s very life as a Trinitarian mystery of persons. The Trinity is indeed the Christian account of God. But that is not to close down the possibilities for other persons of faith sharing in God’s inner life. Indeed very much the opposite, for if God is the God who enters deep into creation and is forever shaping that creation for God’s own providential purposes, then there can be nothing and no one beyond the scope of God’s love. That is the logic of the timeless moment depicted in the Portiuncula.

Michael Barnes SJ lectures in the Theology of Religions at Heythrop College, University of London. He is author of Theology and the Dialogue of Religions (CUP, 2002).

More articles for the Year of Faith:

![]() ‘Thinking Faith’ by Damian Howard SJ

‘Thinking Faith’ by Damian Howard SJ

![]() ‘Faith in the Gospels’ by Peter Edmonds SJ

‘Faith in the Gospels’ by Peter Edmonds SJ

![]() ‘Faith in the Old Testament’ by Nicholas King SJ

‘Faith in the Old Testament’ by Nicholas King SJ

![]() ‘Faithful imagination’ by Rob Marsh SJ

‘Faithful imagination’ by Rob Marsh SJ