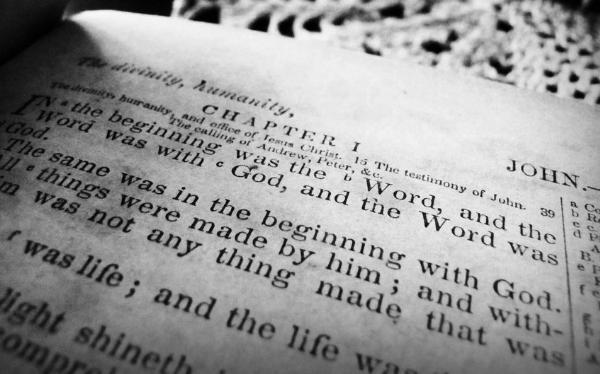

‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.’ This familiar opening to John’s Gospel will be read on Christmas Day, but talking about the Word becoming flesh might appear to be an abstract way of celebrating the birth of Christ. John Moffatt SJ asks: what does it really mean to talk about Jesus as ‘the Word’?

Of all the gospels, the Gospel of John is the most rooted in place. We visit the healing pool at Bethesda tucked away behind the Temple. We are taken to Jacob’s well with Mount Gerazim behind it and we follow Jesus’s route to the Mount of Olives across the Kedron Valley. This gospel also has the most developed dialogue of the four. Rather than a collection of exchanges, parables or wise sayings, we find often-dramatic conversations that break open simple, literal thought patterns and reveal a glimpse of profound realities: Jesus and Nicodemus, the woman at the well, weeping at the tomb of Lazarus, the confrontation with Pilate, and the intense, fragmented, prophetic words of love, belonging and friendship at the last supper. We are presented with the powerful presence of the Son of God - there, localised, a human being in the midst of ordinary human beings, but seen through the eyes of those who learn to recognise the depths within. From Jesus’s first ‘What do you seek?’ to Andrew to his final ‘Follow me’ to Peter, we are invited to enter into a personal relationship of complete and life-giving friendship with the crucified and risen one.

Yet this same gospel begins with what sounds, for most of us, like an astonishingly remote abstraction: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.’ With its deliberate echo of the ‘in the beginning’ from Genesis, the text takes us back to the moment of creation, using a term, logos (‘word’), which straddles the worlds of ancient Hebrew text and contemporary Greek-language philosophy. Words themselves, let alone the abstractions of philosophical speculation, often seem dry and dusty things compared with the richness of personal experience. Ideas, however intriguing, pale beside our loves and hates and the reality in which we revel. But this gospel introduction invites us to read the history of intense, life-giving, personal encounter that follows against the abstraction of a remote, creating Word, present at the beginning of time.

So it is worth trying to understand the intellectual journey that leads to this abstraction. Firstly, because this journey is foundational to the faith in the threefold God that we profess every time we make the sign of the cross. Secondly, by following the journey we gain an insight into the contemplative aspect of thinking Christianity, in which theology and spirituality work together in a harmony of mind and heart. Finally, these apparently abstract ideas provided a basis for the dialogue between faith and reason in the ancient world, and still have the power to be fruitful for the same dialogue as it continues in our own time.

Let us start with the philosophers. Way back in the early fifth century BCE, Heraclitus, brought up in a Greek city on the edge of the Persian Empire, speaks of a logos – a word – that runs through all reality. We only have this from fragments of his writing, so it is hard to say what exactly he meant. But the writings of Plato and Aristotle a century and a half later explore in different ways this suggestive turn of phrase. There is a deep connection between our human ability to ‘know’ reality and the words we use to talk about it and describe it. This suggests, in turn, that there is an essential ‘wordedness’ (if you will forgive the expression) about the world itself that lies beyond our knowing.

For Plato, words (particularly the words of careful philosophical argument) take us beyond the shifting sands of the world we see into a world of ultimate, changeless reality, a world of mathematical and ethical truth, a world of beauty and goodness that underpins the visible world and irradiates it – and, above all, our actions – with the light of value. His most famous image is of the escape from enslavement in the cave, from an imagination drugged by flickering falsehoods into the brightness and beauty of freedom and transforming truth. In this world beyond the cave, reached in a journey of the soul, goodness itself is like the life-giving sun that enables all things to flourish.

His student and colleague, Aristotle, was first and foremost a biologist, trying to order and explain the natural world. He explores the close harmony between our ability to describe in words the nature of the different kinds of thing in the world and to explain why things happen the way they do. Our ability to use words to give an account (logos) of the world is a reflection of real structures in the world we describe – the world is the sort of thing that can be described and understood. The word is out there, a reality in the world.

The philosophers named Stoics, some of whom were contemporaries of Plato and Aristotle, develop this family of ideas further. For Cleanthes, the word is the instrument by which the god of the universe accomplishes his will , like the thunderbolt of Zeus. The word ‘seeds’ realities throughout the cosmos. But the word logos also comes to mean not just a reality in the things we describe, but our very ability to understand, what we call ‘reason’. Yet we can instantly see how thin our word ‘reason’ sounds, when placed beside the rich layers of the ancient vision of logos as our ability deeply to understand reality. And this vision of logos takes us beyond our human minds and into the mind of God itself.

The Jews first encountered the world of Greek thought in the third century BCE and many of their intellectuals were fascinated by what they found. They wanted to show that their tradition was in harmony with this compelling, new-found wisdom. The best-attested of these is Philo of Alexandria, a contemporary of St Paul. In his writing we can see how the ancient Jewish texts that tell of God ‘speaking’ at the dawn of creation and on Mount Sinai find a common ground with Greek-speaking theology in the logos that is the dynamic agent and mind of God.

But there is another important element in the Jewish Biblical tradition. Its texts contain parallel language of the ‘word’ of God and the ‘wisdom’ of God. Importantly for us, the latter tradition transforms logos from an abstract concept into a person. In Genesis we hear: ‘And God spoke’. In the prophets we hear how, ‘The word of the Lord came upon me’. But in Proverbs 8:22ff, Wisdom speaks in her own person and tells of how she played at God’s side, the master-craftsman, as the world was made. It is this personal Wisdom and Word that is proclaimed at the beginning of John’s Gospel, the one through whom all things come into being. The logos springs off the pages of dry philosophical text and becomes a transforming encounter in the person of Jesus of Nazareth, the Word of God made flesh who dwells among us. This Word does not just tell us what to think or do. In his life, death and resurrection, he shows us the true mind of God. That changes everything.

For the early generations of Christians, the language of ‘the Word’ helped them understand why the individual history of Jesus, the God-man, had cosmic significance. We get a sense of a visionary, intellectual enlightenment that runs from the Letter to the Colossians through to the writings of the Church Fathers. But it also helped them recognise that life-giving truth could be found in other cultures and traditions. The world is inextricably entangled with the Word of God that shapes it. All human beings are shaped in the Word to respond to the Word. And thus our God speaks to us all and through us all – indeed through all creation. This theme, first sounded in Paul’s speech on the Areopagus, is also taken up by Clement, Origen and Aquinas.

That vision is, I think, timely for us today as we struggle, like the ancient Christians, to understand the role of our faith in a complex, sophisticated world. It suggests that any impermeable boundary we try and put up between ‘our’ privileged truth and alternative, challenging accounts of reality must be illusory. Any attempt to close off dialogue with the rest of humanity is a betrayal of our heritage.

Above all, there is no boundary between faith and reason or religion and science. That cuts both ways: on the one hand, our tradition may well have a gift for the science and cultures of our day, when they are ready to listen; but on the other, we ourselves, as a faith community, can learn new things as well, if we are honest hearers of the Word.

Finally, if the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us, that changes how we think about truth and meaning. Truth is not something that can be exhausted by the repetition of formulae, ancient or recent. Rather, it is most deeply revealed in relationship and in action, action that is fully human, a creative sign of selfless love, faithful to the will of the Father. We Christians believe many things, but the most important is that we believe in him. And his last words to Peter and to us are not a detailed list of instructions, but the simple, terrifying, consoling and liberating phrase: ‘Follow me’.

And we saw his glory, the glory as of the only-born of the Father, full of grace and truth. (Jn 1:14)

John Moffatt SJ teaches at the Jesuit Institute, South Africa. For more on this topic, see his new book, The Resurrection of the Word: A Modern Quest for Intelligent Faith (The Way, 2013).