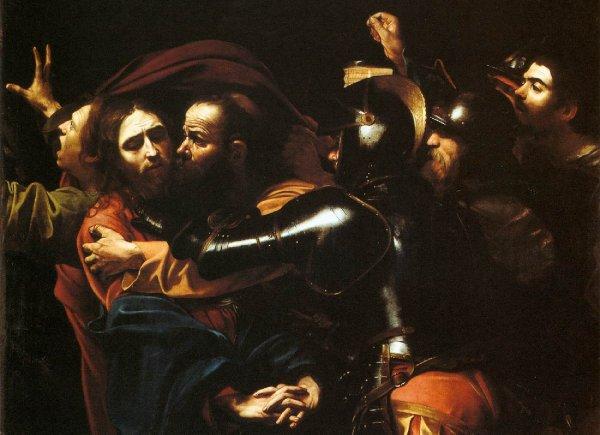

The Taking of Christ is one of Caravaggio’s most celebrated works and is arguably the most famous depiction of the arrest of Jesus. Teresa White FCJ immerses herself in the scene that the artist creates and reflects on the truths about the events of Good Friday that are captured in this painting.

The painting, typical of Caravaggio's vivid, 'chiaroscuro' style, invites those contemplating it to enter into the sights and sounds, the colours and textures, the movement and drama taking place in the early hours of the first Good Friday. Almost inevitably, we find ourselves contrasting what is happening here with the fraught scene which had preceded it: Jesus, alone, praying in agony to his Father, while three of his friends wait a short distance away. The three want to support him, but they keep nodding off, waking up now and then to find him still at prayer. It is that intensely silent time of the night when the darkness is deep and dense. Then the soldiers arrive. In an instant, the stillness is shattered and the darkness slashed by leaping flames from torches and lanterns.

A detachment of guards, carrying weapons, is crowding in on Jesus. Their heavy, clanking armour catches the light of the lantern held by an unarmed man, thought to be a self-portrait of the artist. The scene is one of decisive action and noisy confusion, with the spotlight clearly shining on Jesus, motionless, sad and dignified, and Judas, the traitor. It is a picture of the betrayal of a friend by a friend.

To the left, at the edge of the picture, John, the ‘beloved disciple’, his face full of anguish, is shouting at the top of his voice and waving his arms wildly. He has just come to after repeatedly falling asleep while Jesus was praying. Suddenly roused by the sound of marching feet, he is deeply disturbed by this strange turn of events. But John’s fear is stronger than his dismay at what is happening to Jesus. Hurrying away from the hostile clamour piercing the silence of the night, he moves into the surrounding darkness.

Three of the soldiers are visible in the painting. One, who seems to be the arresting officer, is laying his gauntleted hand on Jesus’s shoulder. He does this with a surprising gentleness. He seems almost reluctant to arrest this refined, sensitive man. Never before has he met anyone who offers no resistance when being taken into custody. Perhaps he is genuinely touched by Jesus’s vulnerability and defencelessness. Perhaps he wonders if there has been some mistake... Another soldier, an older man, whose face can be seen more clearly, looks on with an expression of what looks like sympathy. ‘What could this man have done that we have been ordered to arrest him?’ he wonders. ‘There is no look of a criminal about him. He is a man of God.’ The third soldier peers over the heads and so does the lantern-carrier, shedding light on the scene.

Apart from Jesus himself, and Judas and John, the three helmeted soldiers and the lantern-carrier are the only visible characters in the painting. But there is a strong sense of the presence of other people, unseen spectators in the unfolding drama. Peter and James must surely have been there as well as numerous members both of the cohort, sent by the Roman authorities, and of the Temple police, sent by the Sanhedrin, to apprehend Jesus. They are all witnesses to the arrest of a man who goes about doing good: healing the sick, giving sight to the blind, raising the dead.

Judas has just performed the prearranged sign that has caused the disorder and commotion so clearly represented in this picture: he has given Jesus what will ever afterwards be known as ‘the traitor’s kiss’. His left arm still holds Jesus in the customary embrace given by a disciple to his rabbi. Judas does not look cruel and spiteful. Rather, he looks worried and uncertain, as if he is ill at ease in the role of traitor. It is thought by some that Judas agreed to betray Jesus because he was sure that Jesus, when pushed to the limit, would reveal his power and free himself from his captors. It is possible that Caravaggio took this view, for in the painting, there is a kind of grim determination on Judas’s face. ‘If I do this,’ he seems to be telling himself, ‘Jesus will show what he’s made of. He won’t let the authorities take hold of him. He’ll show them that he is the Messiah, the King of the Jews, and he’ll deliver all of us from Roman domination.’

Though the figure of Jesus is not centrally placed in the painting, it is the clear focus of attention. The face, with its anguished features, its expression of heart-breaking serenity, stands in clear contrast to the agitation of the crowd pressing in on him. Not long before, as he had prayed in agony, Jesus had accepted the cup of suffering that would come to him. The kiss of Judas marks a decisive step on his journey towards death, and everything in him shrinks from it. His heart is wrung because Judas – his disciple, his companion, who ate with him and walked with him, who laughed and sang and prayed with him, who listened eagerly to his words – has betrayed him. To be handed over to enemies by anyone is terrifying, but to be handed over by a friend must be almost unbearable. In the painting we see Jesus drawing back from Judas, his brow furrowed and his eyes down-turned, unwilling to meet Judas’s gaze. There is no trace of anger in Jesus’s expression. It may be that what the artist wanted to depict here is the compassion of Jesus. Does he foresee that, Judas, although he will experience remorse for his action, will before very long lose all hope of God’s mercy and forgiveness?

At the bottom centre of the painting, the eye is drawn to the hands of Jesus, which have a special prominence, and are full of meaning. The hands are not tightly-joined in prayer, as of one imploring God to give strength in a time of trouble and distress. Jesus is about to stand alone and friendless before the people he came to save. His hands tell us that he has chosen to do this freely. The fingers are inter-twined, ‘bound’, as it were, like the feet of a lamb being taken to the slaughter. The gesture suggests that Jesus has made a conscious decision to face the darkness of suffering and death: ‘Not my will but yours be done’. He does not ‘unbind’ his hands in order to restrain the soldiers who come to arrest him. The surrender is not passive, not self-regarding; it is accomplished with total acceptance, because that is what love demands. Yet it is not a blind acceptance. The artist conveys a sense that Jesus is fully aware of what he is doing. He is not being arrested; he is offering himself to his captors.

The hands of Jesus are strong yet sensitive – the hands of a caring, compassionate man, not of a conceited rabble-rouser. They are central in the painting because they tell us that Jesus will face what lies before him with courage, despite the torment, despite the ignominy, despite the apparent failure of his life and work. They express in advance the sacrifice that will be completed the next day on the Cross: ‘Father, into your hands I commend my spirit’.

Teresa White FCJ is a member of the European Province of the Sisters of Faithful Companions of Jesus.