The question of how a loving, all-powerful God could have created a world in which so many people suffer is one with which people at all stages of belief have wrestled, and during the current pandemic it is being put into even sharper focus for many. ‘These questions have their place, even if they are condemned ultimately to fall short,’ says Mark Dowd as he surveys the different responses that he has encountered.

‘I tend to think of an innocent little child sitting on the bank of a river in Africa, who’s got a worm boring through his eye that can render him blind.’ These words of Sir David Attenborough in an interview with The Times in 2008 have been especially uppermost in my mind these past weeks. ‘Now, presumably you think this Lord created this worm, just as he created the hummingbird. I find that rather tricky.’

Tricky? Just a tad. The moral evil of mass murder, rape and torture by freedom-loving humans at least has a free will defence when we are asked to account for the presence of suffering in the world of a loving creator. But tsunamis, tornadoes and diseases such as Covid-19? Where is God is the activity of the spike protein of the coronavirus that penetrates cells in the human body and can lead to death by acute respiratory failure?

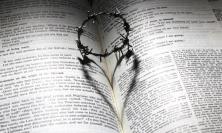

In a feat of great publication haste, Oxford University mathematician Dr John Lennox got Where is God in a Coronavirus World? into print by the second week of April. Dr Lennox has taken on the likes of Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens in public on many an occasion and is an individual who rides the twin horses of scientific enquiry and religious faith impressively. Lennox cites Genesis 3 and human rebellion as a key factor. He asserts that original sin is an adequate explanation for the existence of disease and death, as the moral corruption of our forebears ‘meant that God’s very good creation became flawed and fractured.’ Not being a creationist who believes in a literal interpretation of the first book of the Old Testament, I don’t find this altogether persuasive. A study of complex evolutionary processes tells us that the thorns and thistles of the natural world existed long before the advent of Homo sapiens. Indeed, disease and death, according to Darwin’s theory of natural selection, are integral parts of a development through which genetic information is eliminated, passed on and refined throughout creation. Modern humanity, as we know it, is the product of this very aspect of nature. And it’s not just an insight from the biological sciences. ‘Unless a grain of wheat falls to the ground, it remains only a seed but if it dies it bears much fruit,’ we are told in John’s Gospel (12:24). Life and death are two sides of an inseparable coin. When the light of creation is shone, it always casts an inevitable shadow.

This was an insight I came across first-hand many years ago after the horrendous Boxing Day tsunami of 2004, which accounted for more than 225,000 deaths (about the current global fatality rate of Covid-19). Presenting a documentary for Channel 4, I visited Thailand, India and western Sumatra in Indonesia and heard from people who had lost dozens of family members. In my state of emotional upset I had railed against God and pondered how a loving creator could have fashioned something as destructive as tectonic plates. On a subsequent journey to Lisbon to discuss the 1755 earthquake that occurred on All Saints Day and resulted in a huge loss of life, I pondered the question with Dr John Polkinghorne, Anglican minister and accomplished theoretical physicist. ‘Without those plates, land could not have been forced above the oceans. The surface of our planet would have been, perhaps, a green swamp, impossible for human life’, he told me. He added that the movement of the earth’s crust had, historically, probably been essential for human endeavours in agriculture, as key minerals and ores from beneath the surface had most probably enriched the soil and made cultivation of crops easier. What is beneficial for the systemic whole has some very rough edges for individuals caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. This is nothing to do with divine punishment, or karma. It is the price to be paid for living in a complex natural world, which features both beauty and occasional barbed wire. This inescapable intermingling of positives and negatives isn’t just reflected in closer studies of the natural world, it’s also reflected in some of humanity’s oldest religious cultural heritages. Take the god Shiva in Hinduism. He is both a deity of creation and destruction, and both these elements of eternal energy are contained in the classic dance, the tandava. Or take this beautiful poem from the eleventh century Muslim theologian, Al-Ghazali:

Reflect! The order of life

Is a subtle, marvellous unique order

For nothing but death endears life

And only the fear of the tomb adorns it

Were it not for the misery of painful life

People would not grasp the meaning of happiness

Whomever the scowling of the dark does not terrify

Does not feel the bliss of the new morning…

There remains a central question. Could not a loving, omnipotent creator have just twiddled the settings to keep all the sunsets and leave out the droughts, pestilence and disease? By sheer grace and good fortune, as that Channel 4 tsunami film reached its climax, I got the chance to pursue this very question in the most unlikely of locations. Some sixteen miles south east of the centre of Rome lies the papal summer palace at Castel Gandolfo. It is home to the Vatican Observatory run by a small community of Jesuits, and they were convening a week-long seminar on ‘God and Suffering’, to be attended by some of the most gifted Christian scientists and philosophers on the planet. We spent days on the terrace overlooking Lake Albano and I unleashed question after question upon those gathered in this idyllic setting. Why didn’t God just do a better job of it and leave out all the thistles? A consensual reply came forth. It is not to limit God and reduce his omnipotence if God cannot perform the logically impossible, for example, make two and two equal five. Might it well be that the intrinsic nature of a material world is simply that upsides and downsides are inevitably the price you have to pay for having anything at all? ‘Well,’ I suggested, ‘what would happen if we discovered another planet in which the laws of nature were different and suffering had been eliminated for sentient creatures?’ I was told that there was a fairly solid consensus that the laws of science would be applicable across the universe and, anyhow, in the absence of being able to single out such a suffering-free entity in the solar system and beyond, my question was merely hypothetical. I questioned more and more, until it came down to the crunch.

‘Well, if God cannot create a material world with us in it, without suffering and death, then why create at all?’ It is essentially the same dilemma facing any young couple as they ponder bringing new life into the world. They know their offspring will experience highs and lows, and they will, like all of us, eventually die. But it is exceptionally rare for anyone to suggest they should desist from becoming parents. But of course, God is eternal, and loving and omnipotent. Why, but why, did God then create? I put this to Professor Philip Clayton from the Claremont School of Theology in California and his answer is worth repeating in full.

Anyone who sees the depth of suffering in our world and answers that question simply, doesn’t get it. I would love to imagine a God, who stood and wept and somehow at the last minute felt it was better to have us than to have the divine in eternal emptiness. You and I would probably not push the button on creation. And that God pushed that button and made creation hints at a mystery we do not understand. It hints at a resolution that we can only hope for. God will only be God if the outcome is something so far better than what we see around us that would make it all right. But I can only say that as a wish and a hope and not as an item of knowledge.

It seems we are back to the final parts of the Book of Job, when the haplessly virtuous but tormented figure asks God to make sense of all his trials and misfortunes. ‘Where were you when I laid the earth’s foundations?’ God responds. ‘Tell me if you understand. Who marked off its dimensions?’ (38:4-5) St Paul continues this theme in Romans: ‘Who are you O man to talk back to God? Shall the pot say to the potter: “Why have you made me like this?”’ (9:20)

Abstract discussions on theodicy are, of course, the last thing on the minds of grieving families and friends during this appalling pandemic. It was the Welsh theologian D.Z. Phillips who said that ‘it is easy for us, as intellectuals, to add to the evil in the world by the ways in which we discuss it.’ There are those among troubled believers, who, faced with such questions, simply shrug their shoulders and plead for a respectful silence. I honour that position. But I would also argue for a differentiated response, as this area is surely the greatest bar to the leap of faithful assent for many agnostics and indeed, atheists. We are creatures of reason. Aquinas always maintained that humanity could come to faith through natural law, via intellectual enquiry as well as through biblical revelation. So these questions have their place, even if they are condemned ultimately to fall short.

These last weeks, reading every day about patients fighting for breath, oxygen levels, ventilators and the like, I have been thrown back on the importance of breath in so many religious narratives. It is the Ruach Elohim, the breath or spirit of God, that hovers above the waters at the dawn of creation. In the far eastern traditions of Buddhism, the anapatasati, the system of breathful meditation, is a key element on the path to enlightenment. And finally, there is the image of a crucified and suffering God on the cross who breathes his last and gives up His spirit. How very apt that, in these Covid-19 anxious times, we vouch faith in a God who does not ridicule us or abandon us in our suffering, but in a God who sends his son to die through asphyxiation on a cross. A God who says, this is not the final chapter of the tale. Put your hand in mine. Walk through the darkness of the tomb and prepare for the unexpected – the new life of resurrection.

We look through a glass darkly.

I believe, Lord. Help my unbelief.

Mark Dowd is a freelance writer and broadcaster. He is the author of Queer & Catholic: A life of contradiction (Darton, Longman & Todd, 2017).