There is a famous philosophical proposition that if an infinite number of monkeys sat at an infinite number of typewriters, all combinations of letters of the alphabet would eventually be made and The Complete Works of William Shakespeare would emerge.

The American comedian, Bob Newhart, picked up this conceit in one of his stand-up monologues by suggesting that, if such an experiment was to be attempted, it would need monitors to go around and observe what the monkeys were writing.

In the sketch[i] he plays one of the monitors and as he walks around he is mostly reading gibberish, but suddenly his interest is piqued by one monkey…

‘Harry, hold on, post 15 here has something! I think this is famous or something...’

Newhart then reads aloud over the shoulder of the monkey.

‘To be, or not to be: that is… the gizornan plan.’

Whenever I hear that a new work about the Gunpowder Plot in in production, I always carry that naive hope of Newhart’s monitor that perhaps this time they will try to tackle the complexities and get beyond the caricatures that have swirled around the subject for centuries. In particular, as a Jesuit with an interest in the Tudor/Jacobean period, I long for the project in which the role of the Jesuits will be explored with some understanding of what was going on at that time.

Thus it was with a reasonable interest that I approached the viewing of Gunpowder, an offering from the BBC to play over three Saturday nights in the run-up to 5 November. Having read some of the introductory materials, the promise of an alternative reading of a well-known event was attractive and sounded hopeful.

Unfortunately, having viewed the first episode, I think all we have found is the gizornan plan again.

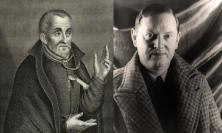

It is really good that the BBC are pouring such heavy-duty resources into the treatment of such a big historical topic. The production values are high – impressive sets, big name actors, the swish of the costumes and the candlelit interiors combine to create a stirring atmosphere, although I was distracted by one of the characters, Sir William Wade, who dresses as if he is Orson Welles doing a sherry commercial.

If the idea was to let people know that the lot of the Catholics during the 16th and 17th centuries was pretty grim, then the piece succeeded. Two executions were depicted rather graphically, so I hope viewers weren’t eating at the time. Executions were brutal, but should they be shown so explicitly? Perhaps electronic deaths are so clean that we need to be reminded of the reality? It is a point that could be argued.

But it was when we hit the narrative core and the cast of assembled characters that things started to unwind, and you wondered whether the driver of this car really is in control of the vehicle.

It is the challenge of a screenwriter to take a book and compress the narrative line, simplifying it so that the spirit of the original text is retained, even if certain cherished people or events are adapted for the new medium. The legendary Hollywood screenwriter, William Goldman, is famous for being able to pull off this sort of faithful adaption – his screenplays for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Princess Bride, Marathon Man, etc., show a master at work. One could argue that the task of adapting a novel is easy because you can play with fictional characters; however, when you are purporting to be writing history, things are trickier, but not impossible – Goldman, for example, did it brilliantly in his adaptions for All the President’s Men and A Bridge Too Far, gaining a well-deserved Oscar for the former.

It is in this department that the Gunpowder script, thus far, seems to be failing badly. The writer is playing fast and loose with people and twisting them into different periods of history in order to load the dice of his narrative. Examples (unfortunately) abound, but one vivid slice of this writing is the execution of the character of Lady Dorothy Dibdale, who is said to be in charge of Baddesley Clinton in the English midlands. Baddesley Clinton does indeed exist[ii], but it was a place owned by the recusant Ferrers family; there was a celebrated search of Baddesley Clinton during a Jesuit conference in 1591, but the hiding places were so effective that no one was ever captured there.

So who was Lady Dorothy Dibdale? She appears to be a fictional character. Why was she shown as being executed in 1605 in so summary a fashion by the peine forte et dure method that had been condemned by Queen Elizabeth after the execution of Margaret Clitheroe in York in 1586?

On the political topics, the question of the Spanish threat seems also to be imported from Elizabethan times and the Spanish Armada in 1588. By the time James I came to the throne, Spain was not seriously considering any adventure against the English. Indeed, the apparent indifference of the Catholic powers on continental Europe was one of the factors that drove the gunpowder plotters to plan for an internal solution as no help was coming from abroad.

The Jesuits have appeared mainly in the shape of three characters – Henry Garnet, who was the mission superior, Fr John Gerard and a ‘Fr Smith’. The latter, another fictional creation, bizarrely appeared to be about twelve years old and was executed by hanging, drawing and quartering. He seemed to be included mainly to show how barbaric such a death was going to be.

Henry Garnet is being explored, but so far Gerard is a colourless character, so it is unclear what his role in the overall drama might be. In reality, John Gerard was a remarkable person who, by 1605, had led a charismatic missionary life and had already escaped from the Tower of London. The one thing that Gerard said in the first episode of Gunpowder does not bode well for accuracy: he is possibly being teed-up as foil for the pacifist Garnet, as he takes a line which appears to be generally supportive of armed rebellion. In reality Gerard, like Garnet, was strongly against any actions of violence against the crown; indeed, in 1603, someone had tried to recruit John Gerard to the Main/Bye rebellion, but he had tried to get word to the new king that a plot was afoot.

So far then, the breeze-blocks of history are being fitted into Gunpowder’s fictional edifice, which really does not bode well for responsible historical drama.

However, I have only viewed the first episode, and the monkeys are still typing. Maybe we’ll get something better next time, Harry?

Fr Dermot Preston SJ digs beneath the drama to tell the true story of the Jesuits who were caught up in the Gunpowder Plot. Read 'The Gunpowder Plot - a Jesuit narrative' >>

Episode 1 of Gunpowder is available to watch on BBC iPlayer until 21 November 2017.

[i] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=raWExtCKA08

[ii] https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/baddesley-clinton