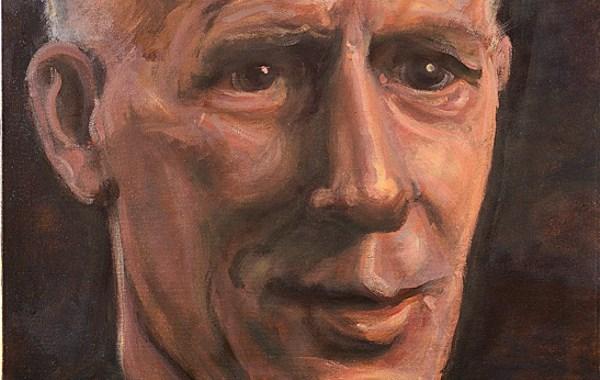

This month, the Jesuits in Britain’s 2014 calendar turns its attention to a French Jesuit theologian who had a huge influence on the Second Vatican Council. James Hanvey SJ introduces the theology of Henri de Lubac SJ: ‘Basic to his writing and thinking always is the recognition of the dynamism of God’s presence and action’.

A major theme that runs through the theology of Henri de Lubac is paradox and mystery. Our existence is confronted with many paradoxes and certainly with much mystery, but for de Lubac the fundamental paradox lies in God assuming our humanity; and the deepest of all mysteries is the way in which the grace of Christ actively meets us in the drama of history – individual and universal. The Church is not something which is marginal or accidental to God’s work, a mere contingent instrument of salvation history: it is central to it – a ‘Mother’ to use a familiar image from the early Christian writers – that brings us to supernatural birth. De Lubac’s writing and thinking covers a vast range, whether it is in French and European literature, ‘patristics’ (the writings of the earliest theologians), theological and cultural history (cf. his three-volume work on Joachim de Fiore) or inter-religious dialogue. But basic to it always is the recognition of the dynamism of God’s presence and action. Although it can appear disparate, occasional and varied, in fact it has a remarkable coherence of purpose and exploration. De Lubac sought to make us aware of all the dimensions of this active, redeeming mystery, so intimately present in every existence and, indeed, which is the very foundation of what it is to be human. In the exploration of the paradox and mystery of grace and human freedom at play in our lives and our world, we come to understand the depth and the drama of what our humanity means and the true nature of the destiny to which it is called.

If we think of de Lubac as living a remote, scholarly and academic life in tranquility, we would be wrong. His own life had its drama and courage, displayed not only during his service in the French army during the First World War and his part in the French resistance movements during the Second. For him, theology and witness were all part of the one reality expressed in thought and life. Hence his determination to help the Church recover the deep wells of its own life so that it could be a source of Christ’s truth, justice, beauty and life in a dark century. He shows us, whether in writing about Augustine or Dostoyevsky, or with Daniélou founding the series Sources Chrétiennes, that scholarship, theology and publishing can also be acts of heroism, resistance and the struggle for human freedom and the Christ, the truth that sets us free. Indeed, his own life as a Jesuit priest and theologian is an example of the paradox and mystery which is a central theme in his theology. From the publication of his seminal work, Catholicism (1938), he challenged a Church still living with the Modernist crisis, viewing the contemporary world – political, cultural and philosophical – with profound suspicion, to return to its sources: patristic, sacramental, spiritual and human. And, from this return (ressourcement), to understand its mission: to engage with the world in all its movements and forms, the great drama of human degradation and nobility, to shape culture and history from the depths of the incarnate Christ who is the light and the destiny of all humanity. The Church has a responsibility to the world, not a mission of evasion; it is also the witness to the unity of humanity which is grounded and realised ultimately in Christ (Catholicisme). To do this was no mere work of patristic excavation, naïve spiritual aesthetics or humanitarian idealism; it was a massive intellectual and imaginative undertaking. It required a whole new theological synthesis, method and approach, that rejected 19th century defensive scholastic apologetics, a recovery of the tradition as a living voice for the present and the future, a dynamic vision of grace and nature, history and humanity, the Church and culture. All this was to bear fruit in the Second Vatican Council, of which de Lubac’s thought was one of the principal theological sources that the Council drew upon consciously and unconsciously.

Yet these achievements did not come without their own cost, especially during what de Lubac described as ‘the dark years’ of the 1950s when he was viewed with extreme suspicion, forbidden to teach and withdrawn from his professorship at Lyon. Throughout, de Lubac never ceased to have an obedient love for the Church and the Society of Jesus. He never ceased to be loyal in supporting his friends and students who also came under the same suspicion and were subject to the same treatment. Here, perhaps we can see that de Lubac’s thought was not just a subtle theological position, nor his method and publications a strategy in some academic cultural war; rather they arose from an intellectual and spiritual integrity. They came from a fundamental contemplation of the mystery which is always their subject: its beauty, truth and glory, at once a personal encounter as well as a theological and ecclesial reality; a lived perception that the mystery of Christ and his grace were inseparable from the call to see that mystery and love it totally in Church and in all humanity.

Nadal, one of the most important second generation of Jesuits whom Ignatian trusted, often said that for Jesuits theology should be undertaken ‘místicamente’, that is, not as a mere intellectual exercise, no matter how brilliant or learned, but as one that arises out of a prayed encounter that shapes our lives and deeds. Above all, it is an experienced reality of the Father, his inexhaustible love made real in Jesus Christ through the constant action of the Holy Spirit – of the Triune God at work in all things, the unconquered kingdom of grace which searches for us.

De Lubac’s thought is sensitive and nuanced, especially in his theology of the intimate interplay between grace and nature – a grace that is ultimately at the very source of human nature in its desire for God, but we should not miss the political nature of his work and its vision of Christian humanism. Whether he is in critical dialogue with Marxism or Anarchism, setting out the theological case against anti-Semitism, or critical of the Church’s own ‘worldliness’, his thought is always grounded theologically in the Incarnation: the source of humanity’s healing and hope, holding both the memory and call to realise the nobility and dignity of every human person who bears the imago dei/imago Christi. Only in Christianity can the unity of all humanity and the dignity of each person come to its fulfilment. Yet this is not Christian triumphalism, rather it is the revelation of Christ compelling the Church to enter the world for the sake of her Lord who is the bearer of all that it means to be human. There, in the very drama of human existence, to engage with it, shape its structures and culture, so that all women and men, whatever their nation, creed or status, can give expression to their dignity and thereby give glory to God, who did not, and does not, count the cost of loving humanity. Indeed, it is the Council itself which succinctly but potently expresses this mission: ‘Through her work, whatever good is in the minds and hearts of men (sic), whatever good lies latent in the religious practices and cultures of diverse peoples, is not only saved from destruction but also healed, ennobled, and perfected unto the glory of God, the confusion of the devil and the happiness of man.’ (Lumen Gentium, §17). As Pope Francis has reminded us, the Church can only live this mystery of her own life as the sacrament of salvation not from her power and prestige, but from her poverty, a poverty which liberates her to live absolutely from the infinite depth of the self-empting Triune Life. (Lumen Gentium, § 1)

In the thought, vision, courage, ecclesial love and humanity of Henri de Lubac, we can always find a resource to help us with this vocation.

For a perceptive introductory discussion and description of de Lubac’s thought, see Hans Urs Von Balthasar, The Theology of Henri de Lubac (Communio Books: Ignatius Press, 1991)

Fr James Hanvey SJ