Born on 23 January 1585, Mary Ward founded the congregations for women based on the Jesuit model that we now know as the Congregation of Jesus and the Loreto Sisters. She faced frequent and powerful disapproval as she pursued the path along which God was leading her. Theodora Hawksley celebrates Mary Ward’s remarkable capacity to resist opposition and to hold on to the truth that she had discerned, and highlights five ways in which we can follow her example.

One of the things I love about Mary Ward was her remarkable ability to hang on to the truth of her vocation amid a firestorm of opposition, and to do so with great grace, freedom and humility. From the beginning of her religious vocation until the end of her life, she faced significant opposition: first, as a young woman, from her parents and her spiritual director; and then from Jesuits who opposed her vision for women’s religious life, from assorted bystanders – the English clergy chief among them – and from the Holy Office and the pope himself. The opposition varied from pressure from those who loved her and considered opposition from her spiritual director, through stonewalling and obstruction, to slander and rumour: opposition from properly constituted sources of authority, as well as just ‘haters’. And all of this happened against a background of societal opposition in the form of assumptions about what women could and could not, should and should not do – which Mary Ward, to some extent, internalised in her early years and subsequently resisted.

Her capacity to resist this opposition and to hold on to the truth that she had discerned, is remarkable. She does not get broken by the constant opposition, and nor does she become hardened by it. What can we learn from Mary Ward about how to discern, with freedom and humility, in the face of opposition and difficulty?

1. Seek space and preserve it

… after businesses, I go (with fear to have assumed something) to find myself in God, without any will, or private interest, and with a will only to have his will; which I cease not until I find, especially in that particular wherein I feared to have lost it.[i]

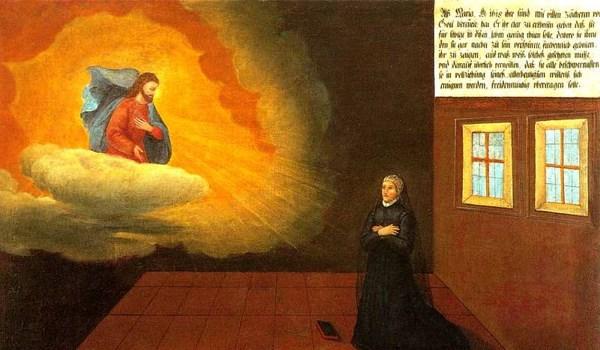

‘The Painted Life of Mary Ward’, a series of paintings that show her spiritual journey, doesn’t show much of the opposition Mary faced. We see her parents talking over her head, trying to arrange a marriage, but we don’t see Mary dealing with the cardinals of the Holy Office, or in prison in Munich. What we do see depicted very often is Mary in solitary prayer, or alone with Christ. Her ability to keep that space of prayer open is key to her freedom. Whatever is happening, she finds a way to be alone with Christ: she allows him to clear out, just as he does in the Temple, all of the people who are trying to sell her versions of what she should be and do. She makes space to rest, to listen. And she is not just checking in to inform the Lord of her decisions: it’s clearly a conversation, and Jesus is often depicted speaking and gesturing.

The solitude she seeks before God is not just an echo chamber for her own ideas and feelings. Mary remains clear that the truth she seeks is not ‘her truth’, but God’s truth:

Veritas Domini manet in aeternum, the verity of our Lord remains forever. It is not veritas hominum, verity of men, nor verity of women, but veritas Domini, and this verity women may have as well as men: if we fail, it is for want of this verity, and not because we are women.[ii]

2. Live hand-to-mouth, even when it’s costly

Faced with opposition, there is a temptation to ‘go beyond the leading’ – to make ourselves more certain than we are, present ourselves to others as more sure than we are, and tidy up the loose ends of our discernments. Mary Ward showed herself remarkably able to live hand-to-mouth from what she was given by God, preferring to move step by step, even when this brought further difficulty and ridicule, than to reach for a complete solution before it was shown to her.

This was a self-conscious attitude, and in a few places in her writings we see her contrasting this hand-to-mouth dependence on verity, which she felt was so crucial for her and her sisters, with the Jesuits, who had more learning on which to depend.

A letter to the papal nuncio in 1621 gives three good examples. All of them relate to her decision to leave the Poor Clares, and the subsequent years of discerning a way forward:

… [there] came suddenly upon me such an alteration and disposition, as only the operation of an inexpressible power could cause, with a sight and certainty that I was not to remain there [in the monastery], and that I was to do some other thing – but what in particular I was not shown…

I had a second infused light in the same manner, but much more distinctly, showing that the work to be done was not a Carmelite monastery, but something greater for God, and so great an augmentation of his glory as I cannot declare, but not any direct particulars, what, how and in what manner such a work should be. After this light was past, I reflected on it with some sadness… to have still all denied me, and nothing proposed in particular seemed somewhat hard, and besides, I was anxious about how to govern my affection in these two contraries for the time being.

A great fuss was made by diverse spiritual and learned men, that we should take upon us some rule of life that was already confirmed; several rules were procured by our friends, both from Italy and from France, and we were earnestly urged to choose one of them. But they seemed not what God would have done, and the refusal of them caused much persecution, and all the more because I refused all of them, but could not say in particular what I desired or found myself called unto.[iii]

3. Be clear-sighted about self and others

Facing opposition can make discernment very difficult. It can make us question our own motives more than we should, or doubt our instincts: critics can have a ‘gaslighting’ effect. It can also make us less willing to question our own motives. Where we are bound up with a particular cause or work, opposition can erode our freedom in relation to it. When we begin to be identified with a work, with no remainder, discerning our role in it becomes much more difficult.

Mary Ward’s spiritual notes and correspondence show us just how self-aware she is: sure of what she has received, and strongly connected to the work, but aware that God can do what he wills through whom he will. At the same time, she’s not forever questioning herself: her trust that this is God’s work extends to a sense that this is God’s work in and through her, with all her imperfections.

We can see this in some retreat notes written during the ‘Praxedis affair’, in which a Sr Praxedis, backed by some of the English Jesuits, caused significant disruption in the Liege community with another vision of the way forward:

…somewhat troubled, I repeated often that he [God] could do what he would, and by whom he would, asking myself, ‘Why not by any other, as well as by me?’ Looking back to the beginning of my call to this course of life, I saw in particular how hardly, and with much ado, I was brought by God to do the little I had done… That with those graces, anyone else would have been moved as soon, and many far sooner, and that this good had no being or place in me, except by the working of his grace… Then, turning with God with intent to confess my own nothingness, I found (by force of will, against my knowledge), I would still be of importance, and a necessary person. Then sad, I said, ‘What, still something in my own sight, notwithstanding all these reasons and truths to the contrary? Well, my Lord, I am content with this want, pardon it and punish it as you please.’ Coming to conclude, and offering myself to God, I saw myself little and of less importance for this work. God’s will and wisdom seemed great, and his power such, and of such force, as strongly to affect in an instant, or with a look, whatever he would. [iv]

4. Resist pressure, not people

Mary Ward had an amazing ability to keep relationships and friendships going, in spite of serious differences of opinion.

We can see this in the way she deals with friends and allies, for example her spiritual director, Roger Lee SJ, to whom she made a vow of obedience. Although she increasingly disagreed with the way that he was proposing as her own sense of her vocation became clearer, she never just humoured him or obeyed him outwardly while doing her own thing inwardly. We can see in her spiritual notebook how much she tried to submit her will to his. This is important because the temptation to become a ‘lone ranger’ in the face of opposition is significant, as is the temptation to disinvest spiritually in relationships of obedience.

We see it, too, in the way Mary Ward deals with her enemies. She is incredibly straightforward, to the point of naivety, with the people in the Vatican with whom she has to deal. When she meets the pope about her request for approbation, she tells him to pray about it! Her companions also talk about her willingness to forgive:

When she had received any injury, it was her special care first to find within herself an entire pardon, deep and heartfelt, not formal and verbal, then to pray for them and seek out occasion to render them service, and this with efficacy but not without prudence, knowing and avoiding the effect of their ill-will and malice, as also to discern what in them was good and what bad.[v]

Interestingly, the code word that the first companions use for their enemies in their correspondence is ‘Jerusalems’. It’s a telling choice, I think: these enemies and trials are painful, but they are not outside of God’s purposes.

5. Friendship

Lastly, I think the key is friendship. I mean this first in the sense of friendship with God, and ‘friend’ is perhaps the most important way that Mary Ward experienced and talked about God: she calls God ‘friend of friends’.

As a young woman, Mary Ward was very ardent and had great desires to be a martyr – she spent a lot of time thinking about how and when it would happen (probably influenced by the fact that two of her uncles were Gunpowder Plotters). But as she grows up, we see her distancing herself from this self-immolation kind of devotion, and from devotional practices ‘made by constraint’ rather than out of love. For Mary Ward, Christ is not so much a lover who demands proof of her love or constant suffering, and she certainly doesn’t have a ‘Jesus, it’s you and me against the world’ mentality. What she has is a very steady friendship.

Mary Ward did not make a habit of being misunderstood or lonely, either. Her correspondence with the early companions shows her not in the least self-absorbed, but not a burning martyr either. She’s also obviously capable of being a friend to herself, and I like this rather more than self-love or self-acceptance. She has a capacity to take care of herself sensibly, to bear with her faults even as she sees them.

Finally, here’s Mary Ward herself on freedom:

Freedom: that things desired were still desired, and with an efficacy and readiness to do them, but without solicitude; things contrary disliked, but without anxiety, the mind equally satisfied whichever of these contraries should happen. The chief effect: one loves, or avoids, according to knowledge [already discerned], one is ready to do, or not do, yet indifferently resigned whatsoever happens; one sees the danger of averse things, but without fear, anxiety or trouble, only a quiet confidence that God will do his will. In conclusion, one is free from all, and desires only one thing, which is to love God, and here one remains free and contented… This disposition gives no new insight as to what things should be done or how, but only the truth of things present and already known and understood, loving and rejecting as there is cause to do so, and equally resigned with what God shall permit.[vi]

Theodora Hawksley is a theologian specialising in peacebuilding and Catholic Social Teaching.

[i] From Mary Ward’s ‘Spiritual Notebook’ (Liege, October 1619).

[ii] From ‘Three speeches of our Reverend Mother Chief Superior made at St Omer having been long absent’, St Omer, December 1617).

[iii] From Mary Ward’s ‘Letter to Nuncio Albergati’ (Köln or Trier, May/June 1621).

[iv] From Mary Ward’s ‘Meditation on the calling of the apostles’ (Liege, October 1619).

[v] From Vita E. [a life of Mary Ward], §194.

[vi] From Mary Ward’s ‘Spiritual Notes’ (Spa, July 1616).