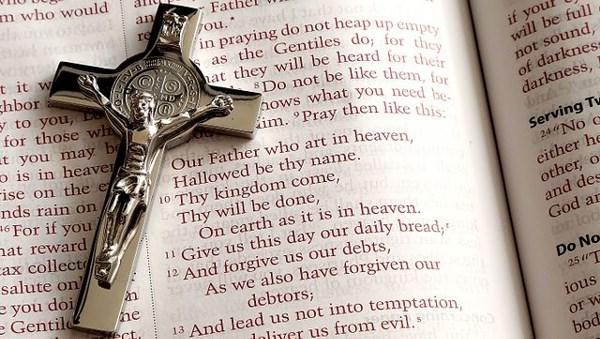

Pope Francis’ concern about the wording of the Lord’s Prayer has generated plenty of debate, and if that makes us more attentive to the working of the Spirit then we should embrace it. However, we ought not to be seeking a perfect translation, says Nicholas King SJ, with support from this Sunday’s second reading. ‘The function of the divine Word is to set us free, not enslave us.’

You have to be careful about words. There have been ruffled feathers in the past week because the pope indicated a certain dissatisfaction with the Italian translation of the Lord’s Prayer, ‘do not lead us into temptation’, indicating that the God whom we address as ‘Father’ could not possibly do such a thing. The French bishops, meanwhile, have changed ‘do not submit us to temptation’ into ‘do not let us go into temptation’. Probably it is best to think of the Greek word in question as signifying ‘testing’ rather than ‘temptation’; that makes it more like ‘seeing what we are made of’ than ‘alluring us to make evil choices’.

In the second reading for the Third Sunday of Advent, taken from the earliest document of our entire New Testament, there is a warning against quenching the Spirit. That may be the context in which to contemplate this issue, for the Spirit was the very tangible force that all the New Testament authors knew so well that they never troubled to define it. They knew that Jesus had brought it, and that human beings are often a bit frightened by it. At the point at which we join it this coming Sunday, Paul is very nearly at the end of his First Letter to the Thessalonians and is, in effect, just ‘signing off’. He achieves this with a series of eight imperatives, which might be translated as ‘rejoice all the time, pray unceasingly, give thanks…don’t quench the Spirit; don’t disdain prophecy; test everything; hold onto what is beautiful; steer clear of every form of evil’.

Now unfortunately the word for ‘test’ here is different from the one translated as ‘temptation/testing’ in the Lord’s Prayer; in 1 Thessalonians it is the word you use for checking whether gold is pure or not, whether it is the real thing. So it is not really connected with the issues that were so widely bruited over the last few days. But there is something important going on in this set of imperatives and prohibitions: there is an openness about the former to the unceasing work of God, the exhortations to ‘rejoice’, ‘pray’, and ‘give thanks’ (from which we have our word ‘Eucharist’). The prohibitions, on the other hand, warn us against closing down that work; the Thessalonians (and we) are not to ‘put out the Spirit’s fire’, nor to ‘regard prophecy as insignificant’. Instead, our task is to listen out for what ‘rings true’, and to ‘hold fast to what is noble’. Do you see how in all this we are being warned not to close our hearts to the Spirit?

And there lies the clue; in this early, heady time of the first preaching of the gospel, our forerunners, and especially Paul, were aware of the freshness that had broken into the world in the shape of Jesus’s gospel, and above all in the decisive event of the Resurrection. You cannot legislate for that, only try and keep the windows open for the powerful wind that is the Spirit, or keep the flame burning, not give in to our temptation immediately to quench it. Words matter very much indeed; and they can exercise a heavy weight, resisting the Spirit’s gentle whisper, unless we keep our lightness intact. For Paul, as for his beloved Jesus, the function of the divine Word is to set us free, not enslave us; but when we get too exercised about meanings, we can too easily forget that our task is to rejoice, pray and give thanks.

That important function of words in part accounts, of course, for the anger that has been provoked by the recent hapless translation into English of the Roman Missal; both the outcome (the language in which it ended up) and the process (the ostentatious refusal to consult) seemed to go against the freedom that is certainly the mark of the Spirit. There were those who thought that after a while people would get used to the new translation; but that is now manifestly not the case. Words matter; and so does the freedom that Jesus and the Spirit bring.

Finally, to return to the question where we started, of God leading us into temptation, sometimes we need to gaze in humility at the words of a difficult text and see where freedom lies. The fact that a text is difficult can never be an excuse for getting rid of it or ignoring it, or trying to change it; our task is to stay with it, and wrestle with it, to see what God might be saying. Above all, let us apply the Pauline injunction from what he says to his Thessalonians, and ‘test everything, and hold onto what is beautiful’. If we do that, then we shall not be far from what God is seeking to say to us and, above all, we shall be refusing to quench the Spirit.

Nicholas King SJ is a Tutor and Fellow in New Testament Studies at Campion Hall, University of Oxford.