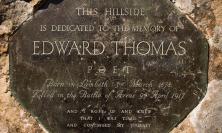

A few weeks before he died, I got a letter from my grandfather. I remember laughing as I read it – it was vintage Grandpa. I’d written to him a few weeks earlier, telling him about my experience of walking the first part of the Camino Ignaciano, as he had always been a keen hill walker. He wanted to know whether I had been with a companion, or whether the photographs I had sent of me sitting on a rock were ‘selfies’, a concept with which he was only vaguely acquainted, but of which he clearly disapproved. He then told me I ought to write to the Archbishop of Canterbury and Pope Francis to ask them what their solution was to the problem of evil, and ended the letter in Eeyore-ish fashion by saying, ‘Since the 1960s and the advent of rock and roll, the world seems to me to have been getting worse and worse, and I do not see it improving in my lifetime.’ He died peacefully in his sleep a few weeks later, with the world still showing no signs of improvement.

As an older man, John was a convinced pessimist, rationalist and atheist. It had not always been so, however, and the bookshelves in my grandparents’ house told the story of a young man who, like many of the post-war generation, had cherished a hope that human beings could, with good will and reason, set about improving the world. But the decades that followed seemed to show that hate, selfishness and factionalism were stronger than reason and so his hope ended up, quite literally, getting shelved. Quite simply, there were no reasonable empirical grounds for hope, so he didn’t have any.

Although it may seem counterintuitive, I think my grandfather’s sense of darkness has a great deal to do with authentic Advent hope.

Today, our connection to biblical language of light and darkness is weak. Without thinking about it, we switch on car headlights, press light switches and watch the streetlights flicker on automatically as the evenings get longer. If you are anything like me, this unthinking ability to cancel dark and create light is so ingrained that I often press light switches during power cuts, momentarily forgetting that they will not work. We are so accustomed to keeping darkness at bay that it is hard for us to connect on a visceral level with what darkness meant in the ancient world. Artificial light has blurred the distinction between day and night, but then, the hours of darkness retained something of that unknown, chaotic character of the first darkness in Genesis. With the night came vulnerability and insecurity, isolation and danger from wild animals. Except for the small light shed by a lamp or fire, the darkness could not be pushed back, and day could not be hurried.

When our Advent readings, particularly from Isaiah, use the language of darkness, this experience is what they are evoking. Isaiah is writing for a people invaded and subjugated by a foreign power, and taken into exile in Babylon. Life there was precarious, vulnerable and lived at the mercy of foreign rulers. When Isaiah talks about darkness, he does not mean a cosy winter evening with nothing much to do, but an experience of disorientation, vulnerability and helplessness: ‘turning his gaze upward, then down to earth, there will be only anguish, gloom, the confusion of night, swirling darkness. For is not everything dark as night for a country in distress?’ (Is 8:22–23)

There is plenty of this kind of darkness in our world: bloody civil war, political turmoil, resurgent right-wing nationalism, poverty, environmental destruction. Watching the news, we may well feel disorientation and helplessness – precisely the emotions that Isaiah is trying to communicate to us. Yet, surrounded by such overwhelming darkness, we are often reluctant to look at it. Instead, we can begin to succumb to a sort of ersatz-Advent: we turn our gaze inwards, gathering round artificial sources of warmth and light. Unable to bear watching the news, we flick over to watch the unlikely progress of Ed Balls on Strictly Come Dancing. As the world reels from one crisis to the next, we nurse a vague hope that people will come to their senses, or that technical or political solutions will emerge. We may even throw ourselves into activism, but not of the energetic, confident, world-changing kind my grandfather fell out of love with. We no longer believe we can solve the world’s problems, and so we focus on bringing a little light, a little hope, to our chosen corner. All of these responses to the darkness outside are understandable, but in all of them – the distraction, the vague optimism, even the activism – there is a sort of not-looking. We do not want to look at the darkness, because we do not want to admit our feeling of helplessness. We do not want to let in the idea that we are not in control and that, ultimately, we cannot secure our future, our environment, our borders, or the lives of those we most love. We choose to live an ersatz-Advent because we are afraid of the dark.

My grandfather did not succumb to any kind of softly-lit Advent-lite. He did look at the darkness, and he did not have any illusions or cherish any hope unless there was good reason to, which, on his reckoning, there wasn’t. Yet, gloomy as it may seem, I want to suggest that is one half of genuine Advent hope. Advent hope begins with a long, hard look into the darkness, a look that, like the prophet Isaiah, does not shrink from seeing how bad things really are. The purpose of this exercise is not to depress ourselves into inertia: it is to purify our hope.

The other half of Advent hope is the long, loving look. In his meditation on the Incarnation in the Spiritual Exercises, St Ignatius invites us to share in the long, loving look of the Trinity, gazing ‘upon the whole expanse or circuit of the earth.’ (Sp Exx §102) Ignatius asks us to see:

those on the face of the earth, in such great diversity in dress and in manner of acting. Some are white, some black; some at peace, and some at war; some weeping, some laughing; some well, some sick; some coming into the world, and some dying; etc.

Sharing the vision of God in this way is not initially reassuring, and Ignatius does not go on to say, ‘I will see that, from God’s point of view, things in the world are not as bad as all that.’ Rather, what we see through God’s eyes is the full extent of the damage: we ‘behold all nations in great blindness, going down to death and descending into hell.’ (§106) Yet the great beauty of this scene is that the whole thing takes place in the context of God’s saving action in Christ. Before we have even begun gazing into the darkness, Ignatius has told us to call to mind ‘the history of the subject I have to contemplate.’ As we gaze upon the brokenness of the earth, what we are looking at is a world for which God has already given himself, in flesh, in history, in fact. We are looking into the darkness of the night before.

Ignatius’s meditation on the Incarnation dramatises something important: Christ is the ground of our hope. If we believe that light will triumph over the world’s darkness, it is not because we believe in the goodness and reasonableness of human beings, nor because we believe in the inevitability of progress, nor the ability of the human race to control its own destiny. Our hope that darkness will give way to light is grounded only in God, and in the scene we have just witnessed: ‘Thirdly,’ says Ignatius, ‘I will see our Lady and the angel saluting her.’ After the cosmic sweep of the meditation, the scene seems small, provincial, a little pious – it is certainly not the cosmic battle or thunderclap-arrival of the new creation that we might have been expecting. But this small, fragile, human life arriving in the darkness is how God says, eternally and decisively, what was spoken in the beginning: ‘Let there be light.’ As we look into the world’s darkness, all that is good and true may seem too small, too weak, may have to flee into exile, may have its life cut short, may even be crucified – but nevertheless: ‘The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not overcome it.’ (Jn 1:5)

Theodora Hawksley trained as a theologian at Durham University and the University of Edinburgh, initially specialising in ecclesiology before moving on to work on peacebuilding and Catholic Social Teaching.