How can a scientist believe in God? In an article for The Way, Paul L. Younger explains how he answers this question and addresses many other challenges that are levelled at him as a Christian scientist. “It is in personal encounter with God that I accept the Lord’s invitation to proceed ‘way beyond all science”.’

… su ciencia tanto crece,que se queda no sabiendo,toda ciencia trascendiendo ….St John of the Cross[1]

An atmosphere of hostility towards religion in general, and not least Christianity, has been expanding through contemporary culture in recent decades, especially in affluent northern Europe. This hostility has been nurtured by a swathe of popular books written by zealous atheist proselytizers. One of their most common assertions is that science has demonstrated the non-existence of God and that therefore every aspect of religion, faith and spirituality is now redundant.

Authoritative rejoinders to these atheist polemics have been published by so many eminent scientists, theologians and philosophers that there is no need to rehearse their arguments.[2] Indeed, for a large majority of erudite scientists—whether agnostics, atheists or believers—the most irritating aspect of the atheist propagandists is their casual disregard of basic principles of the philosophy of science. For formally, science cannot adjudicate over the existence or non-existence of God, because the domain of science is Nature, and metaphysics lies beyond the scope and techniques of scientific method. Thus, if scientific investigations were your sole recourse, then your only honest position on the existence of God would have to be agnosticism. To embrace faith, or to espouse atheism, requires value judgments to be made, which simply fall outside the domain of science.[3] Disingenuous over-claiming on the scope of science is not only mischievous; it deliberately misleads those who are unfamiliar with the philosophy of science. I am occasionally challenged by non-scientists, emboldened by this loud misinformation, to reconcile my scientific profession with Christian faith.

It seems to me that much of the ‘argument’, if it takes place at all, is increasingly sterile, repeating worn-out clichés ad nauseam. Rather than rehearsing this stale polemic, therefore, I shall focus here on Christian spirituality from the perspective of a career-long research scientist. While this topic may be more amenable to poetry than to prose, it is consistent with a spirit of genuine enquiry to present my perspective in the form of answers to some of the familiar questions.

‘How can a scientist believe in God?’Before answering this question, my scientific training tells me to specify my terms of reference. By any definition, the concept ‘God’ embraces infinity and eternity, and any reality beyond that. Given that humans are finite, and constrained by language and culture, it is simply beyond our grasp fully to understand and articulate what ‘God’ might signify. This does not mean that we cannot talk about God, but it does mean that all discussion about God depends on analogical language.[4] To resort to analogy does not restrict us to theology or metaphysics: analogical techniques are commonplace in many branches of science, especially where direct observations are impossible (for example in deep igneous processes). So analogical language is not only useful, but vital. Yet when it comes to God, analogies alone simply cannot take us to the frontiers of human understanding in encountering the divine.

Notwithstanding this prior disclaimer, for my part the interface of science with faith is expressed by my heartfelt responses to three fundamental questions, which are at once simple yet infinitely profound:[5]

- Why is there anything as opposed to nothing at all? (Hebrews 11:3; Revelation 4:11)

- Why is the universe intelligible, as opposed to complete chaos? (compare Genesis 1:1–2; Psalm 18 (17):5–15; John 1:1; 1 Corinthians 14:33)

- Why do we encounter deep love, in people’s hearts and actions, despite terrible horrors? (Ecclesiastes 3:11; Psalm 36:5–7; Jeremiah 31:3; Ephesians 3:17–19; 1 John 4:16)

It is in pondering these questions that I find my mind and heart captivated by God the Creator, who not only calls forth order out of chaos (Genesis 1:1–2), but sustains existence from each moment to the next. I am not particularly interested in intellectual considerations. Rather, I conceive my encounter with God as a sustained relationship. For me, this finds expression in the sacraments and in daily practice, of lectio divina (prayerful scriptural reading), the Examen (reviewing the blessings and challenges of each day) and silent meditation. As a scientist, my instinctive predilections attract me to prayers of gratitude for the beauties of Nature, seeking opportunities to contribute to God’s providence for all creatures and nurturing the habit of living one day at a time.

So often, I feel that sincere discussions over the ‘existence’ of God end up bedevilled by talking at cross-purposes: very frequently, people who regard themselves as atheists are ‘not denying the existence of some answer to the mystery of how come there is anything instead of nothing …’. Rather, they are,

… denying what [they] think or have been told is a religious answer to this question …. that there is some grand architect of the universe who designed it … a Top Person in the universe who issues arbitrary decrees for the rest of [us] and enforces them because He is the most powerful being around. Now if denying this claim makes you an atheist, then I and Thomas Aquinas and a whole Christian tradition are atheistic too.

But a genuine atheist is one who simply does not see that there is any problem or mystery here, one who is content to ask questions within the world, but cannot see that the world itself raises a question.[6]

Like very many other scientists who are Christians, I feel compelled to face the fundamental questions about existence, intelligibility and love in the full awareness that my scientific knowledge and techniques will not avail me in my quest. It is in personal encounter with God that I accept the Lord’s invitation to proceed ‘way beyond all science’.

‘But surely you aren’t a creationist … ?’The term ‘creationist’ has become synonymous with a minority of Christians who deny the existence of evolution, on the grounds that they consider the scientific narrative to be in conflict with the scriptures, especially Genesis 1. These ‘creationists’ are largely confined to small, non-orthodox, pentecostalist Churches, predominantly in the USA and their mission territories. Small pockets of the tendency can be found in some Nonconformist Churches, though this is by no means the norm.

One of the most revered pioneers of palaeontology, the Scottish geologist Hugh Miller (1802–1856), wrote profuse theological reflections on his field observations, eloquently expounding the consistency between different sources of truth.[7] It is unfortunate that the self-styled ‘creationists’ appear to deny the precept that there cannot be any conflict between valid human reason and divine reason. To insist on such a conflict is to betray a concept of a god who is far too small. To argue that God might be impugned in debates on dispassionate reason is to attempt to constrain God’s attributes within puny human categories. This denial of evolution is, of course, a gift to the atheistic zealots, who seize on it as evidence of irrational thinking and then try to generalise this minority position as the norm in mainstream Christian thought. On the contrary, for mainstream Christians truth simply cannot be in conflict with truth: Nil hoc verbo Veritátis verius.[8]

Following in the tradition of Hugh Miller and countless subsequent scientists, many Christians have contributed to scientific discoveries in the unravelling of the history and processes responsible for evolution, including the pioneering geneticist Gregor Mendel (1822–1884), the palaeontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin SJ (1881–1955) and his present-day heirs, and those responsible for decoding the human genome.[9] By the time I studied geology at university, any perceived conflict between scripture and science was long dead. I recall discovering that an eminent visitor was a lay preacher; I prayed with him in thanksgiving for the myriad wonders of rocks, fossils and landscapes.[10]

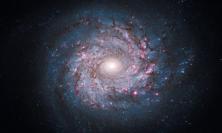

Meanwhile, scholarship at the interface between science and theology continues to advance, not just in relation to evolution, but throughout the natural sciences—from molecules to the entire expanse of the universe.[11] The more we discover about the universe, the more human awe expands (Psalm 8:1–5). To be a scientist is to have a particularly privileged access to the profundities of Nature. Hence my daily prayer commences with thanksgiving for the senses which enable us to delight in creation.[12]

So, to answer the question: obviously I am not a ‘creationist’ in the narrow-minded sense in which a false nostrum is erected to oppose evolutionary science. But I am a joy-filled worshipper of the sole Creator God, who continues to act through countless secondary causes.[13]

‘Enjoying nature is all very well, but how can you reconcile a loving God with pain, suffering and premature death?’If the militant atheists have what they regard as a ‘killer question’ for Christianity it is that of suffering.[14] Yet even the most cursory engagement with the New Testament—and much of the Jewish Bible—reveals sustained exposition of God’s response to suffering and death.[15] The passion and resurrection of Jesus are the fulcrum of all Christian thought and experience. Strikingly, Jesus does not waste time asking why suffering occurs, but rather:

- notes that random events do not discriminate between the virtuous and the villainous (Matthew 5:45), and hence suffering afflicts both the just and unjust, whether this results from human violence (for example Luke 13:1–3), chronic diseases (John 9:1–3) or accidental catastrophes (Luke 13:4–5);

- sets about healing and redeeming the afflicted (see, for example, Matthew 14:14) and, in the process, demonstrates God’s desire to do the same. The Lord’s Prayer itself makes clear that God’s benevolent will is fulfilled in the Kingdom of Heaven, in stark contrast to the frustration of God’s will in our world (Matthew 6:10)—especially by evil (Matthew 6:13).

Despite this clear teaching, many Christians continue to misunderstand God’s loving will. The Lisbon earthquake of 1 November 1755 has often been cited as a devastating blow to Christian beliefs, and thus a boost to Enlightenment atheism.[16] Yet Jesus’ teaching on such events has always been clear (Matthew 5:45; Luke 13:4–5). Divine providence and evil coexist in our finite world (see for example Matthew 13:24–30). We are not promised that suffering will be fully vanquished in this world: ‘The Son of God suffered unto death, not that humans might not suffer, but that their sufferings might be like His’.[17] Yet Jesus continues to heal, and to redeem the sin that arises from the temptation to despair, when suffering and death threaten to undermine our trust in divine love.[18] It is understandable that self-aware creatures deplore the suffering that is encountered in our finite world; but, then again, so does God: ‘Our responding to life’s unfairness with sympathy and with righteous indignation, God’s compassion and God’s anger working through us, may be the surest proof of all of God’s reality …’.[19]

Of course it is easy for an atheist to reject this reading of the world: ‘Only a capricious, mean-minded, stupid god [could] create a world that is so full of injustice and pain …’.[20] Yet, from a scientific viewpoint, it is very far from obvious that the universe could have been arranged in a better way. This is, essentially, God’s riposte to this challenge, as expressed in the Book of Job (38:1–18). To modern science, ever since Einstein’s deduction of relativity and the subsequent discoveries around quantum mechanics, it is clear that the universe expresses both apparently ‘stable’ structures (which venerable Newtonian physics can still describe accurately in many cases) and random physical processes, which are formally referred to as ‘stochastic’ processes.[21] But it is now clear that interactions between stochastic processes give rise to the very structures that we regard as ‘stable’. Hence it turns out that ‘capricious’, stochastic processes are indispensable if we are to have the universe we know (and we cannot know any other).

Stochastic processes occur on all scales in space and time, from stellar nebulae to the cells in every living organism. For the most part, stochastic dynamics generate structures of breathtaking fecundity. Nevertheless, from the perspective of vulnerable, short-lived humans, many familiar stochastic processes threaten life. For instance, lightning strikes can kill. Yet if lightning did not exist, the Earth’s atmospheric ozone layer would be lost, exposing all animals to fatal solar radiation and hypothermia as heat would be lost to outer space. Over longer timescales, the absence of stochastic plate-tectonic processes, such as earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, might be welcome, but all life would eventually become extinct, as nutrients would be mineralised. In our own bodies, stochastic processes are indispensable in cell division, without which no life would continue; and yet the same processes give rise to cancer. While it is understandable to feel aggrieved, from a scientific perspective it is irrational angrily to curse all ‘capricious’ processes, for in their absence none of us would exist to complain in the first place.[22] Of course, one might claim that the balance between stochastic processes and stable structures is poor, albeit there is no scientific basis to reach that conclusion. What we do know is that numerous physical constants are poised precisely at the magnitudes required to allow life to emerge.[23]

So our world emerges as an inherent mixture of blessings and misfortunes. Whether an individual judges this mixture positively is subjective. I get the impression that most humans view the balance favourably. For my part, as I undertake my Examen daily, I always find a surfeit of blessings over desolations, even on the very darkest days. Admittedly, I have yet to endure the extremes of spiritual devastation.[24] Yet the more I persevere with the Examen, the more positive becomes my appreciation of God’s loving gifts and graces.

‘Next you’re going to tell me that you believe in miracles …’Before considering ‘miracles’, it is important to acknowledge that healing exists—most prominently through the work of health professionals. Given that all humans are creatures of God’s love, health care is integral to divine healing. Furthermore, a wider spectrum of suffering is healed by the ministry of the Church community:

To bring to the patient a sense of the presence of Christ and of his fellow Christians, to strengthen his faith and his awareness of the love by which he is surrounded, to restore to him a sense of belonging to a community in which his life matters; all these things might be expected to help his recovery.[25]

I have repeatedly experienced this divine healing at first hand.[26]

But what of ‘miracles’? Many instances are documented of prayer preceding spectacular healing.[27] Yet from a scientific perspective, it is difficult to categorize a given case of healing as ‘miraculous’ on the grounds that medical science does not currently have any explanation; after all, science is advancing continually, and fresh explanations may yet emerge for events that were previously inexplicable.

To obsess about identifying ‘miracles’ risks missing a crucial precept. If we truly believe that God is present in all things, as St Ignatius Loyola emphasizes, then God works in natural processes. But given that God remains sovereign—notwithstanding voluntary self-limitation—then God can overrule normal processes. But this does not constitute a violation of creation, because (as St Thomas Aquinas explained),

God … cannot literally intervene in the universe because He is always there—just as much in the normal, natural run of things as in the resurrection of Christ or in any other miraculous event. [Hence] a miracle is not a special presence of God; it is a special absence of natural causes—a special absence that makes the perpetual presence of God more visible to us. Since God is there all the time, and since He doesn’t need to be mentioned when we are doing physics or biology, or doing the shopping, we are in danger of forgetting Him. So a miracle is … an exuberant gesture, like an embrace or a kiss, to say, ‘Look, I’m here; I love you’, lest in our wonder and delight at the works of His creation we forget that all we have and are is the radiance of His love for us.[28]

This is precisely my understanding of what Jesus meant when he said that the sick are healed ‘so that God’s works might be revealed’ in them (John 9:3).

‘So what difference does it make for you to be a scientist?’At one level, to be a scientist makes no difference at all: anyone from any walk of life is invited to embrace God’s love. But given that I am a scientist, it would be ungrateful to discard my experience and expertise as I accept the Lord’s invitation to communion with the Trinity. So I am called to be the most conscientious scientist I can be; to proclaim my gratitude and praise for all of the wonders of the creation that I have the privilege to observe. But beyond that, I am called to proceed ‘way beyond all science’, to rejoice that ‘my sole occupation is love’.[29]

Paul L. Younger, who is married with three sons, is a well-known research scientist. He has been honoured with fellowships of the Royal Academy of Engineering and the Royal Society of Edinburgh. In 2015 he completed the Spiritual Exercises at the Ignatian Spirituality Centre in Glasgow.

This article was published in The Way, 57/2 (April 2018). To find out more about and subscribe to The Way, please visit theway.org.uk.

[1] ‘… his science grew so much / that he was left unknowing / way beyond all science …’ (my translation), ‘Coplas del mismo hechas sobre un éxtasis de harta contemplación’ (‘stanzas concerning an ecstasy experienced in high contemplation’). See The Collected Works of St John of the Cross, translated by Kieran Kavanaugh and Otilio Rodríguez (Washington, DC: ICS, 1991), 53.

[2] See, for example, Real Scientists, Real Faith, edited by R. J. Berry (Oxford: Monarch, 2009); The Lion Handbook of Science and Christianity, edited by R. J. Berry (Oxford: Lion, 2012); the peer-reviewed, international academic journal Science and Christian Belief, at www.scienceandchristianbelief.org, jointly published by Christians in Science and the Victoria Institute; Alister E. McGrath, Dawkins’ God: From the Selfish Gene to the God Delusion (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015); Terry Eagleton, ‘Lunging, Flailing, Mispunching’, review of Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion, London Review of Books, 28/20 (19 October 2006), 32–34.

[3] See McGrath, Dawkins’ God, especially 155–157.

[4] This is a fundamental principle in the thinking of St Thomas Aquinas, and therefore in that of many orthodox Christians. The principle has been very well expounded in the writings of the late Herbert McCabe; see, for instance, The McCabe Reader, edited by Brian Davies and Paul Kucharski (London: Bloomsbury, 2016), especially 65, 271–272 and 276.

[5] See Tom McLeish, Faith and Wisdom in Science (Oxford: OUP, 2014), especially 183–207.

[6] Herbert McCabe, God Matters (London: Continuum, 1987), 7.

[7] See Hugh Miller, The Testimony of the Rocks, or, Geology in its Bearings on the Two Theologies, Natural and Revealed (Cambridge: SMP, 2001 [1857]).

[8] St Thomas Aquinas, ‘There is nothing truer than this word of Truth’, from the hymn ‘Adoro te devote’, in The Aquinas Prayer Book: The Prayers and Hymns of St Thomas Aquinas, edited and translated by Robert Anderson and Johann Moser (Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute, 2000), 68.

[9] See, for example, Reading Genesis after Darwin, edited by Stephen C. Barton and David Wilkinson (Oxford: OUP, 2009); Martina Kölbl-Ebert, Geology and Religion: A History of Harmony and Hostility. (London: Geological Society, 2009); Amir D. Aczel, The Jesuit and the Skull: Teilhard de Chardin, Evolution and the Search for Peking Man (New York: Riverhead, 2007); Simon Conway Morris, Life’s Solution: Inevitable Humans in a Lonely Universe (Cambridge: CUP, 2004); Simon Conway Morris, The Runes of Evolution: How the Universe Became Self-Aware (West Conshohocken: Templeton, 2015); Francis Collins, The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief (New York: Free Press, 2006).

[10] The late Professor Dick Owen of the University of Swansea; see Thomas Richard Owen, Geology Explained in South Wales (Newton Abbot: David and Charles, 1973).

[11] See, for example, Evolutionary and Molecular Biology: Scientific Perspectives on Divine Action, edited by Robert J. Russell, William R. Stoeger and Francisco José Ayala (Vatican City: Vatican Observatory, and Berkeley: Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, 1998); Denis Edwards, The God of Evolution: A Trinitarian Theology (New York: Paulist, 1999); Francisco José Ayala, Darwin’s Gift to Science and Religion (Washington, DC: Joseph Henry, 2007); McLeish, Faith and Wisdom; and, for a highly readable astronomical discussion, Guy Consolmagno and Paul Mueller, Would You Baptize an Extraterrestrial? … and Other Questions from the Astronomers’ In-Box at the Vatican Observatory (New York: Image, 2014).

[12] Think of prayers such as the ‘Breastplate of St Patrick’, in Philip Freeman, The World of Saint Patrick (Oxford: OUP, 2014), 49–54, and St Francis’s ‘Canticle of the Creatures’, in Francis of Assisi: Early Documents, edited by Regis J. Armstrong, J. A. Wayne Hellmann and William J. Short, volume 1, The Saint (New York: New City, 1999), 113–114.

[13] See Denis Edwards, How God Acts: Creation, Redemption and Special Divine Action (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2010); and Edwards, God of Evolution.

[14] See, for a recent instance, the well-known public figure (though non-scientist) Stephen Fry: Ian Paul, ‘Stephen Fry and God’, at https://www.bethinking.org/does-god-exist/stephen-fry-and-god, accessed 13 March 2018.

[15] Especially the Psalms, much of Isaiah, the Babylonian exile and the Book of Job; see Harold S. Kushner, When Bad Things Happen to Good People (New York: Random House, 1981); also McLeish, Faith and Wisdom, 102–148.

[16] Most of the packed congregation at the All Saints’ Day Mass in the cathedral were killed when the building collapsed. The historiography is far more complex than is usually acknowledged; see Agustín Udías, ‘Earthquake as God’s Punishment in 17th- and 18th-Century Spain’, in Geology and Religion, edited by Kölbl-Ebert, 41–48.

[17] George MacDonald, Unspoken Sermons (London: Alexander Strahan, 1867), 41.

[18] See Herbert McCabe, The New Creation (London: Continuum, 2010 [1964]), 81.

[19] Kushner, When Bad Things Happen to Good People, 191.

[20] Stephen Fry, quoted in Paul, ‘Stephen Fry and God’.

[21] See McLeish, Faith and Wisdom, 183–207.

[22] See my ‘Lost for Words: An Ignatian Encounter with Divine Love in Aggressive Brain Cancer’, The Way, 56/3 (July 2017), 7–17.

[23] This is the so-called ‘anthropic balance’; see Lion Handbook of Science and Christianity, 124–125.

[24] See also Gerald G. May, The Dark Night of the Soul: A Psychiatrist Explores the Connection between Darkness and Spiritual Growth (New York: HarperCollins, 2004).

[25] McCabe, New Creation, 88.

[26] See Younger, ‘Lost for Words’.

[27] See, for example, Rex Gardner, Healing Miracles: A Doctor Investigates (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1986).

[28]Herbert McCabe, Faith within Reason (London: Continuum, 2007), 101–102.

[29] St John of the Cross, ‘Coplas del mismo hechas sobre un éxtasis de harta contemplación’ (my translation), and ‘The Spiritual Canticle’, stanza 28, in The Complete Works of St John of the Cross, translated by David Lewis (London: Longman Green, 1864), volume 2, 151.