‘I had brought a hundred pounds of myrrh and aloes – enough for a king’s burial. But here was a king already buried, if you know what I mean. Not in the jewelled courts of Jerusalem. Not in the palaces. But in a hovel fit only for stinking cattle.’ Rob Marsh SJ gives voice to the musings of one of the magi whose visit to the manger shapes our Epiphany prayer.

I read the words the messenger had brought me: ‘Buried with a hundred pounds of myrrh and aloes’. I had almost forgotten him … God knows I’ve tried! Nothing has been quite right since that fool’s errand thirty years ago in my misspent, mystical youth. And now he’s dead, embalmed and buried with my spices, my myrrh.

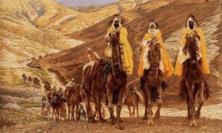

Oh, the journey didn’t seem so stupid back then. The signs were there … in the heavens, in the cards, in the embers of the fire. And when the three of us met, each on the same quest, well, it seemed beyond doubt that we were to be witnesses to some great event. A new king among the Hebrews certainly, but something more, said our oracles, something much more. We rode so confidently for those two years. Can you imagine it? Two years tramping the ways, staying in fleapits, hiding from bandits, constantly fleeced by merchants with no scruples. Two years building each other up with dreams and visions, and ever more exact calculations of the time and place.

And then things began to go wrong. The complex computation was a little off – not a lot, just that there was the Holy City up ahead, Jerusalem of the mountains, crowned by its golden temple … while the charts said, no, down there to the south a little ways.

We trusted our common sense instead of the signs and ended up face to face with that monster, Herod – as bad as and worse than his reputation – trying to conceal his fear at our naïve declaration of our quest: ‘where is the babe born to be king?’

Fools, we were, but fools laden with gifts and fools who had travelled for years, and yes, fools who knew a threat when we heard it. So we set off quietly, dodged Herod’s spies, and this time followed our star maps, to Bethlehem, some little hole in the middle of nowhere. Ironic, really: so close to the centre of the turning world but enough off axis to throw us all askew.

Well, we reached the town by nightfall, bathed as best we could, dressed in our finest, readied our gifts, and wondered where to go. Determined not to be misled again by common sense, we stuck to the stars and passed the big houses, passed the inns glittering with commerce, passed even the meanest hovel, following our star until we couldn’t be mistaken, though we prayed to the gods we were.

A stable, a cattle barn. No mistake … a baby howling inside and a woman shushing it and a man stroking her hair.

They had to be pushed in there, the other two with their gold and incense. I had to push. And the inner voice that had demanded I carry so much myrrh began to make strange sense. A hundred pounds of myrrh and aloes – enough for a king’s burial. But here was a king already buried, if you know what I mean. Not in the jewelled courts of Jerusalem. Not in the palaces. But in a hovel fit only for stinking cattle. And it was cold. And they looked exhausted, afraid, embarrassed. And we added to that as we knelt to do our part. Melchior with his king’s ransom in gold; Caspar burning his precious incense like it didn’t cost an arm and a leg … and me, with half a tonne of burial spices. All trying to maintain our dignity as we crushed into a shed. Which is not to say that man and woman and tiny babe were not gracious – even when they realised that our greatest gift had been betrayal, the hungry gaze of Herod now upon them. We had made them refugees. What was this little family going to do with the stuff we had brought as they fled furtively across the border to be strangers in a strange land? We never knew. At least until today.

We ourselves had to be furtive as we came home a different way. It seemed we were different, too. Anti-climax? It may have been that. Or the fear of what we had done. But we spoke little except to debate the irony of what we had seen. And when that began to run in the same confused circles we spoke hardly at all. Truth be told, I was relieved at the parting of our ways and the fall of silence. More relieved to reach home again. Familiar. Comfortable. But strange, too. In the stillness I was still moving, at night dreaming of fleeing families.

Of course, I made up a story. I couldn’t tell the stupid truth: oh, yes, we gave away our riches to some poor people in a barn. To be honest I tried to forget. But every year at that time I’d find myself back there wondering, wondering what kind of king is born in a cattle shed and enthroned in a trough. And from time to time I would dream of him, glimpse him growing in obscurity, and wonder whether I dreamed the truth or fancy.

These last few years, the dreams have been more frequent and more puzzling. Maybe he was a king after all. His dream-self spoke of a kingdom, God’s kingdom, as he worked his wonders, lived with the poor, scandalised the powerful, gathered the crowds … but then the dreams ended in blood and pain, and I prayed they were false. But it seems not. Buried with a hundred pounds of myrrh and aloes.

But also the rumours: of resurrection, of new life, of a kingdom come. Yet the empires go on. Cruelty goes on. The poor still flee the mighty. And I think I have another journey to make. But where in the world do you go to find the kingdom he promised?

Rob Marsh SJ is a tutor in spirituality at Campion Hall, University of Oxford.

This text was first preached as a homily to the Jesuit Community of the Jesuit School of Theology at Berkeley, Santa Clara University, in January 1999.