During the penitential season of Lent, Thinking Faith will be reflecting upon the ‘seven deadly sins’ by relating each to an illustrative film. In this introductory article, Nicholas Austin SJ looks at the powerful thriller Seven and examines the history of the seven deadly sins, asking what accounts for their perennial attraction.

What accounts for the perduring fascination of the seven deadly sins? Pride, avarice, envy, wrath, lust, gluttony and sloth: throughout the ages, this list of vices has occupied and preoccupied theologians and philosophers, pastors and penitents. These twisted qualities of our characters have captivated the imagination of great poets and playwrights. They have even occasioned T-shirt designs and product names. What is the reason for our permanent love/hate relationship with these seven capital vices?

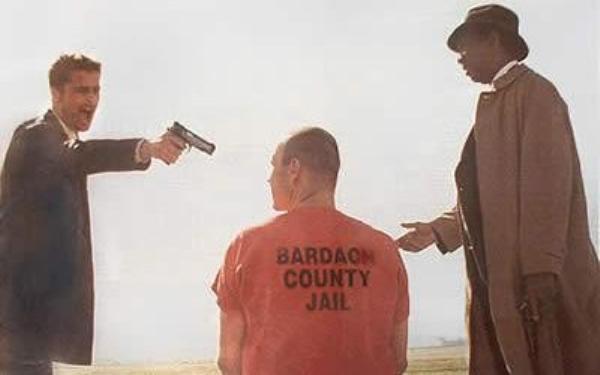

Of all the recent portrayals, one of the most compelling and unsettling has been the film Seven (1995). Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman, in equally forceful performances, play Somerset and Mills, homicide detectives who find themselves drawn involuntarily into a horror beyond their capacity to comprehend. With growing disgust, this unlikely pairing of impulsive, ambitious young cop and his worn, about-to-retire colleague and mentor are witnesses to a series of disconcertingly systematic and sadistic murders, each representing one of the seven deadly sins. An obese man is forced to eat himself to death, manifesting the sin of gluttony; an unscrupulous defence lawyer bleeds to death after being compelled to cut away a pound of his own flesh: greed. And so on, until there are only two sins left: wrath and envy.

The suspense mounts as the two detectives accompany the killer, John Doe (played by Kevin Spacey) into a symbolically desert-like landscape, lured by the promise of finding the bodies of two more of the serial killer’s victims. It is in the car that something of the mind of their captive is revealed: ‘I did not choose, I was chosen ... I won’t deny my own personal desire to turn each sin against the sinner.’ All he did was to take his victims’ sins to their ‘logical conclusions.’ The calculated rationality with which the murders have been committed makes Doe all the more disturbing. Mills can only cope in the face of such evil by angrily dismissing him as ‘crazy’, but Doe retorts calmly, ‘It’s more comfortable for you to label me insane.’ We see Mills shifting uncomfortably in his seat as Doe coolly unmasks the boiling rage within the detective: ‘I doubt I enjoyed my work any more than Detective Mills would enjoy some time alone with me in a room without windows. How happy it would make you to hurt me with impunity.... It’s in those eyes of yours.’ Even the likeable Mills, with whom we have sympathised throughout the movie, is shown not to be without his besetting sin.

But the true twist in the plot comes when Doe, in his vengeful and hateful way, unmasks the sin, not of Mills alone, but of one and all:

We see a deadly sin on every street corner, in every home. And we tolerate it. We tolerate it because it’s common. It’s trivial. We tolerate it morning, noon and night. Well, not anymore.

At this moment, it is not only Detective Mills that is shifting uncomfortably in his seat; it is the entire audience. Earlier in the film, like Mills, we had been able to keep the evil at a distance, at arm’s length: the sin, or the madness, was in the killer, not in us. But when the confrontation with evil itself comes, we find out that we too are implicated, that in the words of a famous Russian novelist, ‘the dividing line between good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being’. ‘Innocent?’ Jon Doe laughs scornfully. ‘Is that supposed to be funny?’

This is the genius of the film Seven. It is not easy to overcome the inclination to deny one’s own sinfulness; it is no small achievement to recognise honestly one’s faults. As Aristotle noted, the power of tragic art is precisely that through the audience’s identification with the hero of the play, it brings the spectator to a humbling and potentially transformative self-awareness. In Seven, the catharsis comes when Mills gives in to his wrath and kills Doe in retribution for the envious murder of his pregnant wife. Fearfully contemplating the abominable horror to which the hero’s tragic flaw has inexorably led, the complicit spectator walks out of the theatre with a desire to be a different person from the one that walked in.

The Idea of the Seven Deadly Sins

Seven portrays retribution, hatred and violence, but the idea of the seven deadly sins arose in a very different setting, one permeated by an awareness of forgiving and transforming grace. Evagrius Ponticus (345-399 AD), a monk of the desert, was the originating genius. With penetrating psycho-spiritual insight, he identified eight ‘thoughts’ or demons that threatened the spiritual progress of the hermit. Just as an athlete must eliminate his weaknesses if he is to compete successfully, so the ascetic must name and uproot the sins that threaten his or her growth. Pope Gregory the Great (540-604 AD) rationalised the list to seven, the number that symbolises completeness. However, it is in Saint Thomas Aquinas (1224-1274) that we find the most systematic explanation of the seven sins.[1]

The first thing to note is that the best term is not the ‘seven deadly sins’, but rather the ‘seven capital vices’. ‘Sins’ might be taken to suggest one-off actions, whereas envy, gluttony, lust and so on, refer to the character traits called ‘vices’: firmly rooted dispositions that lead to sinful actions.

But why are these vices better named ‘capital’ rather than ‘deadly’? While the seven vices of the traditional list can be devastating when they hold a person in their grip, of themselves they are not the most destructive. Sins of injustice are far more ‘deadly’ than sins of gluttony, for example. Rather, these seven are capital vices, Aquinas explains, because they are the source of the other vices: ‘capital’ comes from the Latin caput, which means head. The seven vices are therefore capital because they are the puppet-master vices: it is only in thrall to vainglory, envy or avarice, and so on, that we commit other sins.

Because the seven capital vices are the sources of other sins, John Cassian, an early disciple of Evagrius, compares them to the roots of a tree: ‘For a tall and spreading tree of a noxious kind will the more easily be made to wither if the roots on which it depends have first been laid bare or cut’.[2] The desert monks knew from experience that a superficial approach was not enough: they wanted to name and eliminate these deep motivations for sin that they found within themselves, because only when the root is removed do the many branches of sin wither.

The Glamour of Evil

Nonetheless, what exactly is so wrong about the seven capital vices? In popular culture, the seven deadly sins are often trivialised or even celebrated. Dan Savage, in his book, Skipping Towards Gomorrah: The Seven Deadly Sins and the Pursuit of Happiness in America (Dutton, 2002) writes an apology for sin. He visits examples of the seven, committing each of the sins as he goes along: attending a pro-fat conference for gluttony, joining gamblers for greed, and firing some guns with Texans for anger. The entire book is a rant against the moralistic Christian ‘virtuecrats’ who, in his view, pay scant regard to the American right to pursue happiness in any way one sees fit.

Such celebrations of the seven deadly sins teach us something of importance about the seven capital vices: their enduring attractiveness. The fact is, sin sells. Vice would hardly be so insidious, so difficult to uproot and conquer, if it were completely without its charms or persuasive advocates. It is no wonder, then, that Rebecca Konyndyk DeYoung entitles her excellent book on the seven deadly sins, Glittering Vices.[3]

Once again, Aquinas’s insights are helpful. For Thomas, evil as such never motivates the soul. Human appetite always inclines itself towards something perceived as good, as desirable. The capital vices, therefore, can only motivate and attract the human soul because they ‘participate in some way in some aspect of happiness’.[4] Truly flourishing people, for example, lack nothing and are content with what they have, and avarice seems to promise this kind of self-sufficiency. Similarly, no one can be happy without pleasure, and lust and gluttony seem to offer this in abundance; true beatitude is characterised by peace and rest, and sloth offers some semblance of this; and the self-assertion of pride imitates the true freedom of those who have a healthy self-esteem grounded in humility. As DeYoung comments, ‘The vices have such attractive power because they promise a good that seems like true human perfection and complete happiness.’[5]

In this respect, the seven capital vices exhibit a striking affinity with the contemporary advertising industry. The strategy here is to associate a product with some desirable quality or experience: a shampoo is made to promise self-esteem, as in the L’Oréal adverts (‘Because I’m worth it’); a recent Honda commercial shows a man from the East on a spiritual journey and finding peace when his hand touches the Civic Hybrid. Of course, once we reflect, it is absurd to think that a shampoo could bring genuine self-worth, or a car deliver peace, but advertisements operate at the level of the imagination and the unconscious, not of rational thought, and so prove surprisingly effective.

Given that the seven capital vices, like advertisements, offer seductive promises of happiness, how is it possible to sidestep their power to persuade? Here we may take our cue from the secular realm. Adbusters is an anti-consumerist organisation that has produced some unforgettable ‘subvertisements’ and ‘uncommercials’ to deflate the seductive messages of consumerist advertising. Its memorable Absolut series, for example, skilfully subverts the glamorous portrayal of vodka, shocking the observer into recognising the harsh realities of alcohol abuse.[6] An equally powerful Obsession image, referring to the perfume of that name and portraying in glossy soft-focus a beautiful model bent over a toilet bowl, calls attention to the way eating disorders are exacerbated by the fashion industry’s obsession with female thinness.[7]

Such a strategy should not be unfamiliar to a Christian. During the renewal of baptismal promises at Easter, the congregation is asked, ‘Do you reject Satan, and all his works, and all his empty show?’ The adjective ‘empty’ expresses it perfectly: what the marketing division of the underworld promotes as the sure path to the satiation of all desire, ultimately fails to deliver.

If it is true that the empty promise is one thing that the advertising industry and Satan have in common, then Jesus himself was one of the first ‘subvertisers’. When he was hungry from forty days’ fasting in the desert, the devil said to him, ‘If you are the Son of God, command these stones to become loaves of bread.’ But he answered, ‘It is written, “One does not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of God.”’ (Matthew 4: 3-4) The human tendency to sin is a futile effort to squeeze satisfaction from stones, to turn rocks into the bread that satisfies the heart’s hunger. Such alchemy does not work. Jesus sees through Satan’s hollow offer: only God’s word, and the life that flows from it, truly satisfies the soul’s longings. The devil’s cunning advertisement for sin is subverted by a deeper, more powerful and ultimately more attractive, promise of fullness of life.

During the penitential season of Lent, then, our task is to learn from Jesus how to see through the empty promises of Satan. To this end, Thinking Faith invites us to reflect on each of the capital vices through the lens of a film. These articles will challenge us to recognise how, even though we may be striving to grow in holiness, the pervasive reality of the seven capital vices touches in some way every heart, and to find in that humbling realisation the call to a different way of seeing and being: a way that leads, not to death, but to life. Seven movies, seven subvertisements. The test of the fruitfulness of these reflections will come, however, only after our forty days in the desert with Jesus, at the Vigil on Holy Saturday. For it is only when we stand in the new light of the Easter candle that we shall at last be confronted with the searching question, ‘Do you renounce the lure, the glamour of evil?’ and so be invited to offer a wholehearted and clear-sighted, ‘I do.’[8]

Nicholas Austin SJ teaches Ethics at Heythrop College, University of London.

[1] Summa Theologiae, I-II, q. 84, a. 3,4.

[2] John Cassian, The Conferences, Part V, Chapter X.

[3] Rebecca Konyndyk DeYoung, Glittering Vices: A New Look at the Seven Deadly Sins and Their Remedies (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2009).

[4] Summa Theologiae, I-II, q. 84, a. 4.

[5] DeYoung, p. 39.

[6] http://www.adbusters.org/spoofads/absolut-craze

[7] http://www.adbusters.org/content/obsession-women

[8] Many thanks to Roger Dawson SJ and Ricardo Da Silva SJ for their helpful comments and suggestions.