Director: Doug Liman

Starring: Samuel L. Jackson, Hayden Christiansen, Diane Lane, Rachel Bilson, Jamie Bell

UK Release date: 14 February 2008

Certificate: 12A (88 mins)

No doubt there are a lot of people who go to 12A action films who would identify with a bullied, motherless fifteen year-old, a boy who is tongue-tied in front of girls, a lonely boy who suddenly discovers that he has… well, secret powers: the ability to ‘jump’ through space to other parts of the world. Personally, I feel embarrassed just typing it.

But I suppose this is just a metaphor for social deviance or for talent. Some young people just don’t fit in (and I’m sure they would love to be able to jump to other parts of the world, if only they could). Some young people have really extraordinary skills. Those who work with the young are used to the moment when suddenly a child demonstrates some nascent and hitherto hidden ability—an ability to spin a ball or handle a racquet or epee, or an ability to occupy space on the stage, or a talent singing or jumping or running, or making films, or writing. The question is always (as posed in the gospels) what should one do with it.

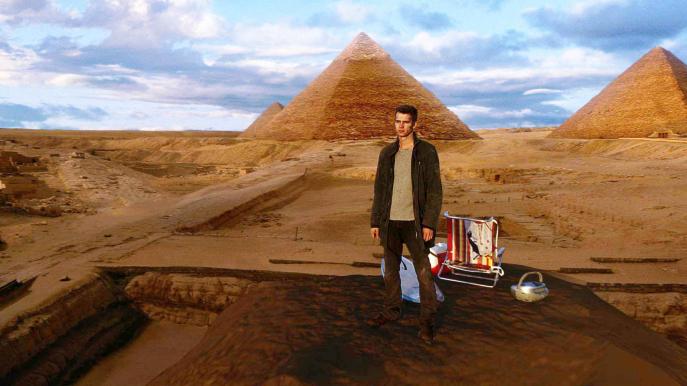

Well, our protagonist (David Rice) faces none of these moral or existential difficulties. He was, as he points out to us (in a voice-over which mysteriously fades away, incidentally) only ‘fifteen, what would you do?’ His choice is to ‘jump’ into banks, help himself to piles and piles and piles of money, leave behind an IOU and opt for a Manhattan penthouse existence on the proceeds (but he’s really nice to the domestic staff, he actually remembers their names).

If only he’d chosen some really alternative existence, I’d feel happier about this film. But he’s so boringly, nauseatingly, resolutely conventional, watching him is like going on FriendsReunited and discovering that the boy you thought would be playing for Arsenal or selling arms in some small third-world country, now has a cat called Bob and works in an insurance brokers somewhere in Stevenage. But at least that’s a vocation (the job in Stevenage that is, not the arms trader). This dim youth just lives the hedonistic life of Hugh Grant’s character in About a Boy, without the prospect of the lonely, fatherless weirdo who changes his life. He’s not even gay. He actually—get this—he actually jumps back to his home town to go out with his high-school sweet heart, the girl next door. It’s as though miraculous ability and seeing the world has actually narrowed his horizons.

I don’t know the novel on which this is based, but there seems as though there was a germ of a darker edge to the story (one ground to dust by the screenplay, however). When a cyclone in the far east kills thousands and flattens whole cities, Mr Jumper sees it simply as a surfing opportunity because of the bigger waves it causes. So at the very start of the film, with the six o’clock news showing God-made havoc and disaster, a young man with super-hero’s powers is just sitting on the sofa, watching it all, munching on pretzels. A metaphor for a presidency, perhaps.

A brief sense of purpose and mission descends around about half-way through, as the Jumpers have to defend their lifestyles: they are pursued (somehow) through time and space by teams of X-file like ‘Paladins’, FBI religious zealots determined to keep the ability to be omnipresent to God. Interestingly, one of the Paladins turns out to be his mother. She left him as a baby so as not to betray him, and now, twenty years later, she reveals herself to her son: she is still determined to do her duty (which implies hunting him down to the death), but has simply given him ‘a head start’.

Personally, I have no doubt that the idle and pointless wealth of these characters would drive me to insanity. But not the young people in this film. For them, lazy, purposeless talent, unearned wealth and flippant ability are an existential statement, not a challenge to it. And what a shame that the rôle of the mother was not developed. Then there might have been something troubling about all this hedonism and talent: you can have it, but mummy’s coming to get you…

Ambrose Hogan