Director: Jon Favreau

Starring: Robert Downey Jr., Terrence Howard, Jeff Bridges, Gwyneth Paltrow

UK Release date: 2 May 2008

Certificate: 12A (126 mins)

On Saturdays during my childhood, my grandfather would buy me comic books. Perhaps he did this as a reward for my having endured the tedious hour spent grocery shopping with my mother. In any case, we would exit the supermarket and enter the drugstore next door where I would pick from the turnstile racks the latest issue of Captain America, Spiderman, The Fantastic Four, Superman, or The Mighty Thor. I long since lost both the stacks of those slim and limp volumes I once hoarded and the habit of reading them. However, I still look forward to any movie based on them even though nearly every one I have seen has disappointed me. That old childhood love persists—like others of its kind—in spite of the repeated evidence of experience.

It’s not obvious why most of Hollywood’s comic book movies should be so unfulfilling. The comic books themselves contain all the elements that make stories compelling: double identities; the protagonist’s metamorphosis from ordinary man into superhero; a love story made interesting and complicated by these identities and this transformation; a villain of equal or greater power who serves as the hero’s double and adversary; a particular vulnerability or Achilles’ heel; an ambivalent relationship between the hero and the people he seeks to assist in which he is often both savior and outcast; and a costume that rivals any animal’s preening display. Despite these narrative resources, most of the movies Hollywood has produced from such stories have failed to mine them, trading the sophisticated pleasures of storytelling for the meretricious ones of the video game.

I am, therefore, happy to report that Jon Favreau’s new film of Iron Man, starring Robert Downey, Jr., Gwyneth Paltrow, and Jeff Bridges, does not entirely disappoint. If it fails to elevate the genre from popular into high art, at least it entertains. One reason it does so is that it stays light. All three actors are clearly outsized for their roles, which remain conventional and one-dimensional. But all three play their parts with high spirits and a tongue-in-cheek sense of enjoyment that infects the viewer. Paltrow plays Pepper Potts, the devoted employee harboring a crush on her employer (like Moneypenny to Bonds) with just the right mix of demureness and wit. She looks a bit like Kirsten Dunst in Spiderman but seems to remember that she’s acting in a comic book not Titanic. Bridges, who looks like Rob Reiner’s evil twin, licks and leers his way through the villain’s role, which he seems to like even more than his cigar. Downey is the best of all, kinetic, quick-witted, ironic, self-aware—at times he recalls the young Pacino and at times the young Charlie Chaplin. He contrasts with the gloomy existentialism of the movie Batmans, the cloying earnestness of Christopher Reeves’ Supermen, and the small town humility of Toby MacGuire’s Spiderman. He is an L. A. superhero, always on the move, talking, pitching, above all, having a good time. It is impossible not to see in the performance some of Downey’s exuberance at working again.

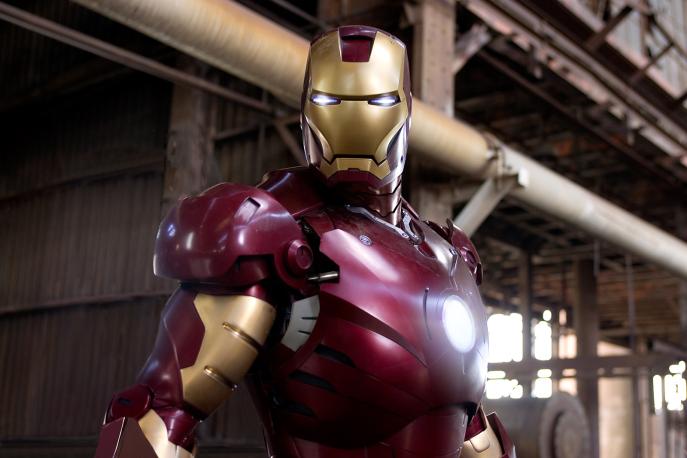

Downey plays Tony Stark, child prodigy inventor and head of Stark Industries, the leading weapons manufacturer in the film’s fictional world. Stark travels to Afghanistan to show off his newest creation—the Jericho missile—where he discovers that his weapons are used not only by the “good guys” (U.S. Armed Forces) but also by the “bad guys” (unnamed and depoliticized troops that look a lot like mujahadeen). Scandalized, he returns to his breathtaking house/laboratory perched on a hill in Malibu, where he suspends all sales of his weapons and creates a futuristic suit of armor (“Iron Man” is a misnomer; the suit’s made of a gold and titanium alloy) for his own use. In the suit, Stark can outfly an F-22; he can fire missiles and power rays; he can withstand bullets and bombs. Unlike other superheroes, Iron Man owes his powers solely to technology; inside the suit he is a normal flesh and blood human being. But like them, he still must figure out what he can do in his new identity. Some of the movie’s best and funniest scenes show Stark designing his suit, trying out his powers, making mistakes, learning to fly, catching fire and crashing. Once he masters his instrument, he flies back to Afghanistan to liberate a village. However, he has enemies in his own company back home whom he must confront when he returns. The traitors within the defense industry prove more difficult to contend with than the Central Asian fanatics.

This sketch of the film’s plot points towards its political message. The real enemy is not the cadres of bald, hawk-nosed jihadists in the hills of Afghanistan but the magnates of the military-industrial complex who sell weapons to both sides. This thesis isn’t likely to convince either side of the political aisle. Conservatives will dismiss it as the same old Hollywood liberalism. Leftists might find that it fails to go far enough. Stark’s repentance, after all, does not cause him to give up the spoils he earned through the sale of his weapons nor does it lead him to question the use to which U.S. troops put his weapons. Even less does it cause him to challenge the amoral intoxication with technology that produced them in the first place. The theme here is redemption through—not from—the love of gadgets.

There is one scene in particular that encapsulates the central political message of Favreau’s film. Having arrived in his sparkling red and gold suit in the middle of the baked clay huts and grey concrete of a village and having killed the worst of the bad guys, Stark sees a group of fighters take hostage some of the women and children of the village. He is perplexed for a moment but then points one of his armour gloves at the people and fires enough bullets to kill all—and only—the hostage-takers. This is the ever-deferred dream of just war achieved by perfect technology, of a world without collateral damage, of one in which force and right are identical. This is not only the new dream of Western warfare; it is also the old Arthurian dream of the Round Table, in which men of another time encased in duller metal battled other men encased in metal in a noble if futile attempt to meld might and right. Perhaps therein lies the secret both to Iron Man’s undeniable appeal and its political and theological limitations. We all secretly want to weed out the tares from the wheat.

But you won’t go to Iron Man for the politics or the plot. Instead, you’ll go for the vertiginous flight simulations, the beyond state-of-the-art computers and robots that populate Tony Stark’s lab, the zest of the performances, the snap of the dialogue, the possibility of redemption (for the character and the actor), and the satisfaction that comes from seeing all the expectations of a superhero movie competently met. Unlike many of his predecessors, Favreau has put the comic back in the comic book.

Glen S. Davis

![]() Visit this film's official web site

Visit this film's official web site

![]()