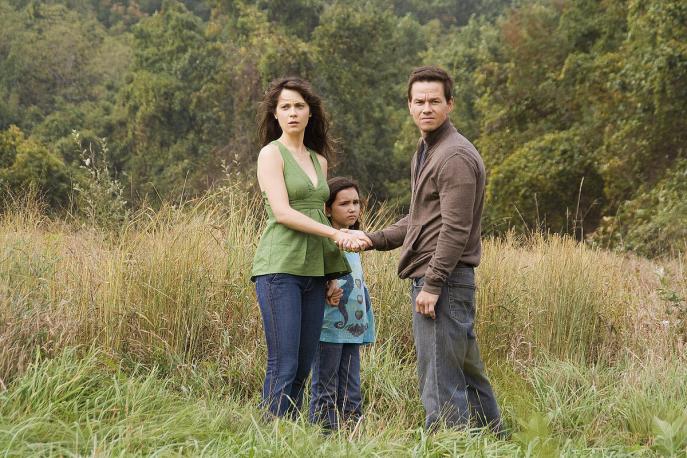

Director: M. Night Shyamalan

Starring: Mark Wahlberg, Zoey Deschanel, Ashlyn Sanchez

UK Release date: 13 June 2008

Certificate: 15 (91 mins)

This is a terrible movie. Some critics suggested that the wooden acting and leaden script might lead to its kitsch rehabilitation, while others detected a deep green cruelty in its multiple depictions of suicide. The few iconic moments – dead bodies dangling from trees or falling from buildings, the opening sequence of angry-looking clouds in a darkening sky – are swamped by facile, ill-formed ideas and unconvincing performances.

Although the story is ostensibly about the end of the world, taking familiar riffs from horror flicks and science fiction B-movies, the drama is situated in the main characters’ failing relationship. The tension between world-changing events and childish marital spat undermines both stories simultaneously. The wife’s sin of eating desert with a man who is not her husband is trivial against plant life’s revenge on humanity. At the same time, the resolution of the film is not in the inexplicable end of the attack, but in the couple’s decision to have a family in post-apocalyptic America, making the near extinction of humanity a mere opportunity for emotional reassessment. Of course, the idea of plants attacking humanity has its own absurdity.

Mark Wahlberg and Zoey Deschanel lack chemistry as the married couple: M Night Shyamalan’s dialogue is pedestrian: conversations are either functional plot explanations or vague exclamations of despair. The cinematography is dull: when plants attack, we get shots of grass in the wind, and high tension gets slow motion, inevitably.

It is tempting to look behind the dismal surface for clues to Shyamalan’s intentions. Are the brutal suicides expressing anger at man’s exploitation of the planet? Is the film an ecological allegory- even if allegory does not need to cling so closely to a literal threat? Is it a study of American paranoia? Is it about terrorism? Is it a warning against trusting any single man with the duties of producing, directing and writing the same film? Speculation is far more entertaining than actually watching the film, but is ultimately about as unsatisfying and inconclusive.

Despite the number of deaths – and their increasing absurdity and brutality – the camera inevitably flinches from showing any gore. Nobody about whom the audience might care is killed. The same lack of depth is revealed in the film’s attitude to science. Wahlberg’s character is a biology teacher and recites the scientific method like a rosary: yet the threat is defined as “an act of nature that we won’t ever fully understand” by a scientist who hasn’t noticed that science’s success depends on a less pessimistic approach. Elsewhere, Einstein is quoted as an authority on ecology. He might have made a fair point, but the theory of relativity is neither biology nor morality, and Einstein qualifies as an expert in neither area.

There is also the fundamental problem that the environmental disaster targets humans and apparently ignores all other life forms. Plausibility aside, Shyamalan is tacitly endorsing the idea that humanity and nature are distinct entities – and in opposition. It might be that the film has an environmentalist subtext, but it firmly subscribes to a model of exploitation and separation.

This shallowness is the real flaw in the film. Torn between the toxin as a metaphor and a literal exploration of its progress, The Happening is neither action adventure nor thoughtful allegory. It is a beautiful expression of knee-jerk environmentalism – which harms the serious ecologists by fuelling a conservative backlash – combined with an unimaginative vision of human nature. Between the received ideas and strained script, Shyamalan has made an art film with the class of a zombie flick and a thriller with the tension of a romantic comedy.

Gareth Vile