27 April is the Feast of Saint Peter Canisius. In 1897, Pope Leo XIII issued an encyclical to mark the 300th anniversary of Canisius’s death, in which he referred to the Jesuit as, ‘after Boniface…the second apostle of Germany’[i]. What did he do to earn such a title?

Peter Canisius was born in the Netherlands in 1521. Like many characters of his time, he defied his parents’ wishes in order to study theology, and he was initially strongly influenced in that regard by Devotio Moderna, a lay pietistic movement. It was while he studied at the University of Cologne that he met and was directed in retreat by Pierre Favre. He completed the Spiritual Exercises of St Ignatius Loyola and went on to become the eighth member of the Society of Jesus. It was during the three decades after his profession to the Society that he worked for the reestablishment of the Catholic Church in Germany, which had been greatly shaken by the Reformation.

Canisius established the first Jesuit house in Germany in 1544 in Cologne, the only sizable German town that had remained loyal to Rome. By the time the first Jesuits appeared in Germany, Luther, Eck and all the other valiants of the Reformation struggle had disappeared from the scene. Nonetheless, it seemed as if the Reformation was about to be completely victorious; indeed, 90 percent of the population had already gone over to Protestantism. The Catholic Church, demoralised and in disarray, could no longer offer serious opposition to the continued spread of the new doctrine, and even in Rome the complete secession of Germany from the Church was expected in the immediate future.

After the Peace of Augsburg in 1555 and the official recognition of the Lutheran presence in the Roman Empire, consolidation of the Catholic position demanded a profound spiritual renovation. In June 1556, Canisius was appointed by Ignatius to be the first superior of the German Province of the Society of Jesus. The Jesuits had realised from the beginning that a successful campaign against the Reformation could be waged only if the conditions within the Catholic priesthood were first improved. As Favre wrote: ‘It is not the case that the Lutherans have brought about the secession of so many people from the Roman Church through the apparent righteousness of their teaching: the greatest blame for this development lies rather on our own clergy.’[ii] Thus the Jesuits appeared in Germany not at first as opponents of Protestantism, but as reformers of the Catholic priesthood.

The Jesuits understood from the beginning that the German language represented the most powerful stronghold of Protestantism. The people heard German sermons, read the Bible in German and sang German hymns, and soon lost through this alone their intimate union with Rome. The national literature which was flourishing at the time as a consequence of the Reformation completely severed the connection of Germany with the Latin culture of the Roman Church.

Canisius was the first to take account of this fact, and for this very reason he became the most successful champion of the Catholic cause in Germany. He realised that Catholicism’s struggle with Protestantism was not least a fight of the printing press, and that victory would fall to that party which could create an effective literature of propaganda.

As Canisius wrote, ‘In Germany a writer was accounted of more worth than ten professors.’[iii] He therefore recommended the establishment of a special Jesuit college for writers, which should apply itself to the production of the requisite polemic literature in the German language. At Rome and Trent, he urged the appointment of able theologians to write in defence of the Catholic faith. He persuaded Pius V to send annual subsidies to the Catholic printers of Germany and to permit German scholars to edit Roman manuscripts.

The most important factor in the re-Catholicising of Germany was, however, the educational activity of the Jesuits. The college became the major symbol in the renaissance of Catholic strength, resilience and enterprise. By 1580, from Paderborn and Heilgenstadt in the north to Luzern, Innsbruck and Halle in the south, from Trier in the west to Vienna and Graz in the east, the three German-speaking provinces of the Society were operating, or just at the point of opening, nineteen schools.

These institutions had more than a religious impact, most notably at tertiary level. In the rough chaos brought to the intellectual life of Germany by the Reformation, many German students left their own country for the universities of Paris, Louvain, Douai and Pavia. To stem this debilitating emigration, new universities were needed and reform of the older ones became imperative.

The Jesuit colleges did a great deal to revitalise the Catholic Church in central Europe in the 25 years after the death of Ignatius Loyola, and Peter Canisius was a leading architect. Some of the newer colleges, such as those at Hildesheim, Worms, Erfurt and Munster, were in areas where the Lutheran population was large, and the patience, industry and dedication of Canisius and his fellow teachers created for many Protestants a new image of the Catholic – converts were made.

Religious instruction in the Spiritual Exercises; mildness and friendliness to the Protestants; instruction in the catechism; and the erection of numerous schools – these were the means by which the Jesuits, under the leadership of Peter Canisius, set about the Counter-Reformation in Germany. But the great success attained by the Society of Jesus led some Protestants to believe that the Spiritual Exercises, by which so many laymen and clergy had been regained for the Catholic Church, must the ‘very work of the devil.’ As the Lutheran theologian, Wiegard, cried at the time,

The Turk hews off heads with his scimitar and everyone is horrified at it … But this murderer of souls has with his book (The Spiritual Exercises) whetted and drawn his sword, for he hews down souls to destroy them forever and deliver them as prey to Satan.[iv]

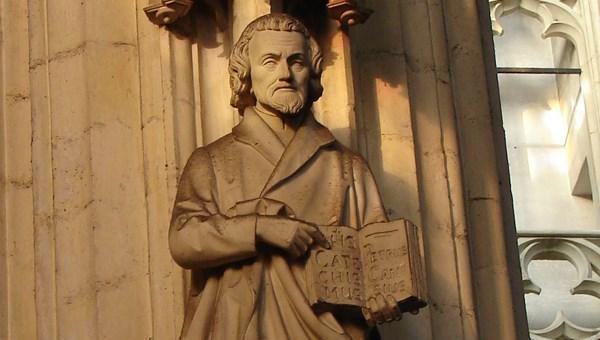

Canisius was a pioneer of Jesuit education, but he exerted his most permanent, personal influence through his writings. Of primary importance are his catechisms, which appeared in three different forms and, adopting a Lutheran technique, were illustrated with woodcuts. The Summa Doctrina Christianae, first published anonymously in Vienna in 1555, contained 213 questions and answers.[v] It was intended to be a compendium for universities and graduating classes of Jesuit schools. A later, shorter catechism of 59 questions[vi] was essentially a summary of the Catholic Church’s doctrine and was used for giving first religious instruction to children. A third edition[vii] contained 124 questions and was introduced into secondary schools as a textbook for religious instruction.

Though Canisius made no claim to the originality of his ideas and was without literary ambition, the catechism is his most ingenious achievement. Translated into many languages, it was used throughout Europe and in mission countries. The fact that until the 19th century the name ‘Canisius’ in German was synonymous with ‘catechism’ is proof of the popularity and importance of his catechetical work.

Canisius’s greatness lies in the fact that he was entirely aware of the tasks of his time. He inspired German Catholics with confidence and a new sense of the faith. He displayed great tact and understanding of the needs of the German people, and worked zealously to reconquer the German lands where the Protestant faith originated.

At his canonisation in 1925 Canisius was awarded the title of Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius XI. Pope John Paul II, speaking on the occasion of the 400th anniversary of Canisius’s death, paid tribute to the vigour of his pastoral work, particularly among young people. He spoke of Canisius’s ‘heroic obedience’ in the ‘service of the truth’

Daniel Kearney is a former headmaster at an independent Catholic college. He is currently Head of Religious Studies at Leweston School in Dorset.

Listen to this short account of the life of St Peter Canisius SJ

[i] Pope Leo XIII, Militantis Ecclesiae (1897), §2

[ii] ‘Memoriale’: The Spiritual Writings of Pierre Favre (Saint Louis: The Institute of Jesuit Sources, 1996)

[iii] James Brodrick SJ, Saint Peter Canisius (Loyola Press, 1998)

[iv] Ibid.

[v] This increased to 223 in a later, post-Tridentine edition published in 1566.

[vi] Summa Doctrina Christianae per Questiones Tradita et Ad Captum Rudiorum Accomodata, published at Ingolstadt in 1556.

[vii] Catechismus Minor se parvus Catechismus Catholicorum, first published in Vienna in 1558 or 1559 and which appeared in later editions also under the title Catechismus Catholicus or Institutiones Christianae Pietatis