I once heard a memorable homily that gave eloquent expression to the idea that the structure of the liturgical year is not a matter of doing what we did last year again and in exactly the same way. Yes, each year we live the same sequence of Advent and Christmas, then Lent and Easter, with blocks of Ordinary Time in between. But every time we approach one of those seasons, each of us is changed from the person who celebrated it the previous year. So it’s never a matter of doing it all over again; instead, every year we bring our changed selves to familiar patterns, and thereby we create something new.

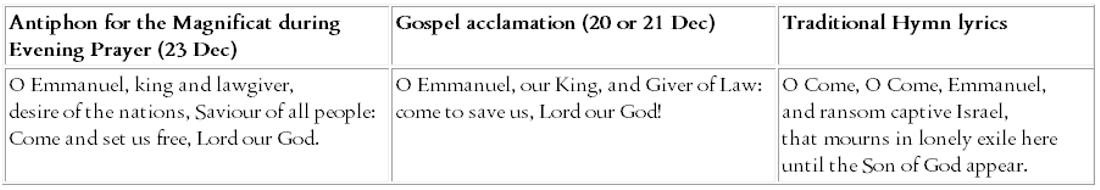

The cyclical nature of life and liturgy is also at play in the sequence of the O Antiphons. The last antiphon to be professed in the Liturgy of Hours is the first that appears on the hymn sheet when we sing ‘O Come, O Come, Emmanuel’. Consider, too, that when we play a neat Scrabble trick with the antiphons, reversing their traditional order and taking the first letter of each, we spell the Latin word, erocras: ‘tomorrow I will be’. This promise points us towards a future that we anticipate but cannot lay claim to, because tomorrow never comes.

But of course, the promise is already fulfilled. We have been rescued, shone on, taught – all of those things that we have prayed for when we recite or sing the antiphons. O Emmanuel suggests that we are consigned to wait with ‘captive Israel’: we mourn ‘in lonely exile here/until the Son of God appear’. But Christ has appeared – been born, and died, and raised from the dead. So what happens ‘tomorrow’? What are we waiting for?

Take a step back from these questions and think not about why we wait, but about how we wait. To be dormant in captivity is a sign that something is corrupt: the guilty prisoner rests easily. The captive who is held unjustly is restless. And so Advent is not about sitting around passively until there is a new arrival in the crib on Christmas morning. Advent, and in fact our whole lives as sisters and brothers of that child in the manger, requires us to wait actively; it requires response and choice, even radicalisation. The radical choice that we have to make is to become exiles.

An exile is someone who is separated from the place they call home. That relationship defines them. Without that connection, they would be free from the mournful longing for a particular place, but they would then just be a wanderer. Our task is to make ourselves exiles rather than wanderers: to orient ourselves towards God and long to abide in Him rather than to wander aimlessly in separation from Him. It’s a twofold process: to cultivate a deepest desire for God; and to recognise why we are exiled, distanced from Him, to recognise what we are held captive by.

The Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius are the map par excellence of this terrain. Coming to understand God’s inexhaustible love for us and then, secure in the knowledge of that love, identifying the disordered attachments that navigate us away from the riches of the Kingdom, are the first steps that Ignatius asks us to take as we seek to give ourselves in the best vantage point to our home. ‘Turn to me and be saved, all the ends of the earth.’ (Isaiah 46:22)

The exile has known home but is now separated from it, and so her cry is all the stronger because she already knows what it is she has lost. That is reflected in the nature of this antiphon’s cry – ‘come to save us’, ‘come and set us free’ – which is arguably less specific, more primal than any of the other antiphons. That innate longing is different to the anticipation of rewards as yet unknown – you can’t miss what you never had – and it gives Christian hope its unique dynamic. We wait expectantly for what tomorrow brings, even though we have already received it.

In the midst of a refugee crisis, to choose exile as a way of life is indeed radical. But that choice is a recognition that we have a room in the Father’s house but are not yet within its walls – we are exiles from our home. We are in a constant state of flux, where endings are beginnings and vice versa, where we do the same things differently, where we wait for something which has already happened... it’s unsettling, but that’s ok. This agitation is the restlessness of the captive, the desperate longing of the exile, and it serves to keep us awake and alert, and ready to recognise the one we wait for, who is always already here.

‘Our hearts are restless until they rest in you.’

Frances Murphy is Editor of Thinking Faith.