On 27 January each year we remember the victims of the Holocaust, and are encouraged in particular this year to reflect on what it means to be ‘Torn from Home’. Andrew Hadik tells the extraordinary story of Joseph Dombovary-Treuenberg who, as a young Jewish boy in Budapest during the Second World War, was taken away from everything he knew and loved, but whose life was saved by miraculous interventions by, among others, a Jesuit priest.

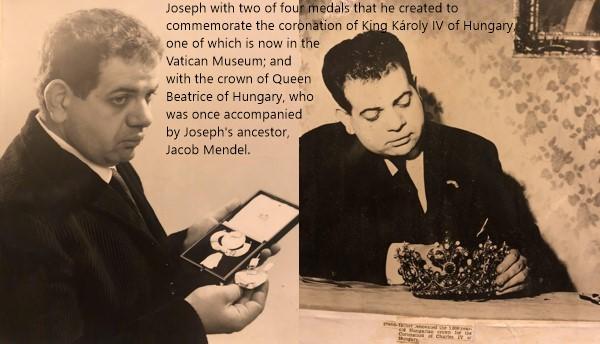

Joseph is the sole surviving member of the Goldschein family. For centuries, the family was distinguished in Hungarian society. One Goldschein ancestor, Jacob Mendel, was honoured for his loyalty to King Matthias Corvinus, who created the dynastic position of Praefectus Judaeorum, ‘Jewish Prefect’, especially for him in 1482.[1] Mendel’s descendants, Joseph’s relatives, continued to hold prime positions in politics, crafts, business and law in Hungary for generations. Only very few members of his family survived Hitler's rule.

In 2016, I started visiting Joseph in order to record his experiences in Budapest during the Holocaust. He told me, ‘I wish to pay tribute to the Jesuit community who saved my life when I was thirteen. I wish to recognise in particular a priest, a family and an individual who defied all dangers to keep me safe.’

The decades before Joseph’s birth saw Hungary in crisis. The end of the First World War saw the abolition of the Hungarian monarchy, held at the time by King Károly IV, now Blessed Karl of Austria, and with it the end of the rule of law. In the years that followed, the country lost two thirds of its territory and over 10 million inhabitants with the Treaty of Trianon (signed at Versailles on 4 June 1920), which was an economic disaster. The Goldscheins had been jewellers to the crown and, despite the hardship, had managed to rebuild and continue their jewellery business.

When Joseph was born in 1931, his father, Dezso, fought hard to rescue something of the past achievements of his predecessors in the art and craft of goldsmithing, and made every effort to create an idyllic childhood for his children. However, they learned at a very young age to suffer hatred. They had to endure anti-Semitic abuse, being stoned by pebbles, and the wording of a new plaque at Csillaghegy station was read to them: it explained that Jews and Gypsies are forbidden to enter the waiting room. But Dezso did achieve his own childhood dream of building a country house in between the Danube and the mountains, creating a safe enclave for Joseph and his elder sister, Edit-Rozsa. The family spent the summers in the country and the winters in an apartment in the centre of Budapest. Joseph remembers this as a happy time.

But by 1942, when Joseph was ten, all normality and security had evaporated. Each day, Joseph was taken from his secondary school with the other Jewish boys for forced labour. This was a terrifying and humiliating experience, and the journey to the assembly point was fraught with danger. Many times, Joseph was prevented from using public transport, the conductors ordering him off because of his yellow armband that proved that he was Jewish, even though by the rule of law he had to report for forced labour a long distance away. As the war progressed, he worked in bombed buildings, hauling out rubble and debris. Being small, he could fit where others could not. Every bombing raid, Joseph had to walk to the forced labour centre while Budapest was under bombardment.

The Goldschein country house had been taken and given to a member of the Arrow Cross.[2] And devastatingly, Joseph’s father was now dead, killed in a forced labour camp. Dezso had been well aware of the rising anti-Semitism. He knew what was going on in other parts of Europe and that he may not survive. Before he left his wife and children, he had taken Joseph round the family home, showing him some secret places where diamonds were hidden. His father wished to secure his family's survival in case anti-Jewish law dispossessed them of valuables. Dezso deeply believed in a merciful God, who would secure the survival of his children.

Joseph continued in forced labour until the Jews in Budapest were rounded up and placed in Jewish ghetto houses, marked with a yellow star. Extreme overcrowding meant Joseph, his mother, Lenke, and his sister could not find a room. Instead, they shared an entrance hall in a ghetto house at 30 Molnar Street, moving in on 20 June 1944.

On 15 October 1944, the Hungarian ruler, Regent Horthy, issued a proclamation declaring a military armistice with the Allies. This news was greeted joyously but within hours the families in the ghetto house were told that the Arrow Cross had taken over. They were held inside by guards at the door with machine guns. They were ordered to close the blinds and sat inside in total darkness. Joseph tells me he asked the adults to move a wardrobe against the door, he thought this would keep them safe.

The next day the Arrow Cross ordered everyone of working age to assemble. Joseph’s mother, aunt and the other adults had to go, leaving Joseph and Edit alone in the house. They waited, but no one returned, and realising that they had no food, Edit decided they must escape. Joseph was terrified of the Arrow Cross guards but Edit told him to walk with confidence. They were not stopped. They headed for 28 Tomo Street, the address of a non-Jewish friend of their father’s, known to them as Uncle Pista.

Uncle Pista was the first in a long line of people who kept Joseph safe. He took the children in and immediately gave them a meal. But soon came the order that house doors must be left open during air-raids so that house checks could be carried out. Uncle Pista arranged for Joseph and Edit to move to a Red Cross safe house for orphans. After a week, the head of the house, Chaya, asked the children if they had another place to go. She had found out that the Arrow Cross were planning to round up the occupants of the house for deportation.

‘We had only one big room with bunk beds next to each other. One day, an Arrow Cross guard walked in, and he was being welcomed! I watched from a distance to see what was going on. He was in fact a Jew and the brother of one of the girls at the house. He took us out of the house in stages to a nearby comer, so it would not look suspicious and no one, no real Arrow Cross guard, would stop us. My sister took me first to a barber because I looked so dishevelled. He asked where I came from and said I was neglected. I couldn’t say a word. Afterwards, my sister and I went together to a family acquaintance, Zsofi Viktor, a teacher at the Scottish Mission School. But when she eventually came to the school door, she said, “Go away immediately.” Later we discovered that the school was under Arrow Cross harassment and observation. She was trying to keep us safe.

‘We were quite heartbroken, but my sister somehow did not lose her trust in the Viktor family. She said, “Oh, I will take you to Zsofi’s cousin in Calvin Square.” My sister told me: “One child is easily accepted. I won’t come with you. I will watch to see you give me a sign you have been taken in. Then I will find somewhere to go.” I had no idea where she was going. I relied on my sister, she looked after me, she was my little mother and I felt I had lost everything.’

Joseph was accepted by Zsofi’s cousin but the family was large, suffering greatly from the lack of food. Joseph tells me: ‘The children were very hostile and their parents didn’t say a word. I sat, didn’t eat, didn’t drink. I was shown to an isolated, cold room, the first time I had ever been alone and I had a very clear nightmare. The Nazis were at the door asking, “Are there any Jews in here?” The mother said, “No,” but the children ran down the stairs and said, “Yes there is a Jew here”. When I woke up I was absolutely frightened. I felt I had to leave.’ The door was high but Joseph managed to unlock it. It was early, around five in the morning. He did not speak to anyone before he left: ‘I feared everybody. Every human being.’ He set out just as he was, without properly protective clothing. There was snow on the ground, which quickly got into his shoes. He had no aim and no idea of which way to go.

‘I didn’t dare stay or sit down. I needed to look as if I had a purpose so that nobody could suspect I had nowhere to go. But from nowhere a man walked up to me and asked a very simple question: “Are you Jewish?” And I was shaken. I was truly shaken. And I simply said, “Of course not!” It was to me the heaviest of moments when he continued to walk next to me. Then he left me and in deep anxiety I kept walking. The man came back to me after a little while. He said, “If you are in any difficulty, the priest of the Sacred Heart of Jesus Church will help you.” I had a quick idea that he was trying to trick me into telling the truth. I didn’t dare to ask anymore, but repeated “Sacred Heart of Jesus Church”. I didn’t want to lose those words.’

Joseph repeated the words and looked up at the buildings. He didn’t ask for directions in case someone should ask why. Eventually he decided to walk towards the place he used to assemble for forced labour.

‘Miraculously I walked past a corner sign pointing to “Sacred Heart of Jesus Church”. I went up to the church door and looked in. I was surprised to see people pushing a baby at the front of the altar. I didn’t understand until later that I had witnessed a rehearsal for the nativity play. It was a few weeks before Christmas.

‘But I suddenly panicked, I could see a big statue to the right hand side. It was irrational but you must understand that I had been brought up with the commandment against idolatrous images, and I became truly terrified of entering the church.

‘Eventually somebody came and pointed me to a narrow alleyway on the right hand side of the church. Through this, I found a metallic door and a reception at the end of another passageway. I was told the priest was in his residence, and so I waited in the stone-floored room.

‘When the priest arrived he asked me one question: “Have you got any documents?” I had a fake birth certificate from the Red Cross house. It was clear it was fake, it was so faint from being reproduced so many times. The form, which should have been black ink, was grey, while my name, which was added later, was much darker. I had been told only to use it as a last resort. He looked at my fake birth certificate and did not query it. Had he even asked my mother’s name, I would not have known it, because when I was given the fake document at the Red Cross house I simply took it, I did not think to look at it! He then gave me the address of what he called an “Apprentice Home” and a sealed letter to take there and deliver to Lajos Haklik, “Director”.

‘The Apprentice Home occupied a flat in a large block. I was desperate to get to shelter, I knew I could not stay out on the streets. I was pointed where to go and when I went into that little front room, it was full of vapour - Mrs Haklik was washing clothes next door. When Mr Haklik walked in I could only see part of his face because of the steam. I cannot tell you why but I liked him immediately. I trusted him. I gave him the letter and he said, “Come with me, I’ll show you to your room.” I knew he knew the papers were fake, but when Mrs Haklik worried, “I hope he’s not Jewish”, he replied, “Of course not”. He put his family’s lives in danger for me.’

The Apprentice Home normally housed Catholic boys who had been sent to Budapest to learn a trade. Because of the food shortage, all except one had gone back to their homes in the countryside. Joseph stayed there from mid-December until just a few days before the beginning of the Soviet liberation. There would have been little chance of Joseph’s survival had he not been sent to safety by the priest and taken in by the Haklik family, whom Joseph learnt attended the Sacred Heart of Jesus Church. The Arrow Cross were murdering indiscriminately on the streets. On his first night at the Apprentice Home, Joseph was in bed when he heard a shout from outside the window by his head: ‘Jew. Stop.’ Then came rifle shots and what sounded like two sacks falling.

‘I thought it was at me. My room was on the ground floor and the shot sounded like it was in the room. There was a second bed in the room and I thought that a person in it was shot dead. I had my coat over my face and I couldn’t move, I was absolutely petrified. I stayed like that all night and in the morning I saw nobody was there, but I was scared to get up and leave the room.

‘When I did go to find Mr Haklik I didn’t know how to speak about what had happened. But he sat me down and gave me some food, and he and a younger man, Bela Floris, who also attended the Sacred Heart of Jesus Church, explained to me what had happened. There were two bodies under my window because during the night two Arrow Cross guards had shot and killed them before identifying who they were. The guards were apparently young men, teenagers, they had wanted to prove their power. The two men they killed were in fact Roman Catholic, they had been out working for bread and were going home to their families. Mr Haklik and Bela dug graves in the small green area next to the house.

‘Bela Floris was a wonderful man. He had recently lost his wife and child to childbirth and he acted with such an energy to keep me safe and well. When my shoes had worn down and I was freezing, he risked his life to take me to my family’s old workshop where I knew there was a pair of my father’s old army boots. Both the locks had been stamped and there was a sign that read “Former Jewish Property; Government Property”, but Bela said, “This is your shop”. He broke the seals over the locks and, at great risk opened the premises to get out the much-needed boots.’

Soon after Joseph moved into the Apprentice Home, residents of the block of flats were ordered to stay in the communal air-raid shelter indefinitely, so intense was the bombing. To comply with this would have exposed Joseph to the danger of questions. Each flat had a coal cellar, all were padlocked. At first, Mr Haklik locked Joseph in the cellar, but realised that the coal dust was terribly bad for Joseph’s health. He decided to risk taking Joseph to the communal shelter where the Hakliks had been allocated a small space, telling the other residents that Joseph was a Catholic apprentice.

A few days later Mr Haklik found out that a priest was due to conduct Mass. He worried that Joseph would attract attention if he did not know the correct customs. There was no time to teach him, and so Bela again took Joseph out of the house and stayed with him until it was safe to return. They went to a closed-down corner shop, owned by a Christian man who was hiding his Jewish wife in the back room. Bela expected the couple to provide Joseph with food and shelter, but this did not happen. The only public place that was open was the Great Cinema, which was showing Nazi propaganda films.

Bela, in desperation, gambled that the cinema would be safe: why would you go unless you were a Nazi sympathiser? But near the entrance Joseph and Bela were accosted by a uniformed Arrow Cross guard who asked for Bela’s identity papers. Joseph describes:

‘I was shattered as Bela had evaded army service because of his religious conscience, but Bela managed proceedings smoothly. When the Arrow Cross guard put his machine gun towards my chest, I was paralysed with fear, but Bela intervened. The Arrow Cross guard asked nothing but made an army turn and walked away. Then I realised he was the elder brother of my classmate. While in the cinema I feared that he recognised me and was summoning reinforcements for my arrest. But we walked away freely’.

On Joseph’s return to the air-raid shelter, a lady approached him and asked why he had not been present during Mass. ‘I ran to Mr Haklik and explained how frightened I was. Mr Haklik said, “Mrs Brody accused you of being a Jew and I informed her that I have your documents and you are a Roman Catholic. She said she would get her son, a member of the Arrow Cross, to check.” Mr Haklik saw how this affected me and gave me every reassurance he could. He took me out to the entrance of the house and said, “Can you hear the noise? The Germans are at the outer end of Baross Street, the Soviets are advancing. You will be liberated soon.” He gave me moral strength.’

Just days before the Soviets broke through, Mrs Brody’s son came to the shelter. Events moved quickly – when Brody left with the promise of coming back with his men, Joseph escaped the air-raid shelter but was caught in the street and forced to march in a group of men wearing signs round their neck saying, ‘This is the fate of an army dissenter’. Joseph was given the sign, ‘This is the fate of a Jew’.

The most mysterious saviour that Joseph encountered was the man standing at the entrance of a block of flats on the main ring road as Joseph marched by. He grabbed the boy out of the line and pulled him into the building. There were Arrow Cross guards with machine guns at the front, back and side of the line of men. It simply happened that at that moment, none of them had Joseph in sight. Joseph didn’t ask the man’s name and barely spoke to him, he never saw him again. He learned later that the marching men had been hanged from the trees in Rakoczy Square, a few minutes away.

Joseph was reunited with his mother and aunt in another air-raid shelter the day before the beginning of the Budapest liberation, a whole story in its own right. Mother and aunt had been held in a factory by the Arrow Cross with a large group of people, without food or heating. They were eventually put into the dark wagon of a goods train headed to Auschwitz, which was stopped and returned from the frontier by the Swedish humanitarian, Raoul Wallenberg, who sacrificed his young life to save others. Joseph’s sister, Edit, had gone to her grandmother’s old maidservant. The maidservant had befriended another woman in the house, the wife of a policeman, who pretended Edit was her niece. Joseph’s mother had the idea to look for Edit there. Joseph remembers the long dramatic wait before Edit finally came down the stairs.

Even after they were reunited, immediate survival required every ounce of the family’s energy. Suffering starvation, they had to survive on horse-meat, digging up the dead horses (fallen in the bombing) from the ice and snow. As soon Joseph could go and see the site of the family's business, he did. He had to use all his strength to clear the bomb-damaged premises, which were looted of everything; materials, tools, equipment. He had no strength to visit other places to see if more relatives might have survived.

A couple of days after reuniting with his sister, Joseph walked to see the Hakliks. ‘They were overjoyed, they thought it a miracle I had survived.’ Joseph asked them to send a message to the priest at the Sacred Heart of Jesus Church. He did not know the priest by name, simply calling him Josagos Pap, ‘gracious-hearted priest’.

Since writing up Joseph’s story, I got in touch with the Sacred Heart of Jesus Church in Budapest. They replied with information about the priest at the time. His was a Jesuit, Father Jakab Raile, Prior of the Jesuit College, and he is in fact already named as one of the righteous at Yad Vashem, where Joseph has also recognised the bravery of Mr Haklik and Bela Floris. He is known to have sheltered 150 Jews in the church, saving many more by befriending members of the Arrow Cross to make sure they suspected nothing, all the while giving out fake baptismal certificates to Jews.

Joseph and his family owed their lives to these righteous men and women. Without them, there is little doubt there would have been a different end. Between May and July 1944, 12,000 Hungarian Jews were deported to Auschwitz every single day. Jews in Budapest at first evaded deportation, but within two weeks of the Arrow Cross seizing power in the city,

Eichmann’s request to deport Jews to Germany for forced labour was supported. 25,000 men and 12,000 women were rounded up in a week. Even when Auschwitz had ceased to operate, 21 new deportations begun on 21 November. More than 3,000 Budapest Jews were murdered in Mauthausen.[3]

It was hugely dangerous to hide Jews, those who did risked their own lives. Ferenc Kálló, a Roman Catholic priest who had been providing Jews with certificates of baptism, was arrested by the Arrow Cross and killed the following day. On 27 December 1944, two Hungarian Christian women, Sister Sára Salkházi and Vilma Bernovits, who had hidden Jews, were executed. In total, it is estimated that 25,000 Jews were hidden in religious institutions and Christian homes.[4]

What was it that made Mr Haklik, Bela Floris and Father Raile act as they did? When asked, individuals who saved Jews often said that they simply saw a person, a child, in need of help. They often had the view that anybody would have done the same.[5] But that was not the case. Joseph speaks movingly of how other relatives thought themselves safe, only to have their lifelines ripped away. The obstructive immigration policies of the United States and Sweden had tragic consequences for Joseph’s family. Joseph’s father tried and failed to gain a US visa before his death, and Joseph’s cousin Eva had her Swedish visa revoked and was deported to Auschwitz.

It is little wonder that, given the fate of so many others, including his relatives, Joseph feels the actions of the rescuers he encountered in Budapest were and indeed still are so powerfully meaningful. The strength and humanity they showed is of great comfort to Joseph. They responded when so many more turned away. Father Raile and others like him embodied the words sometimes attributed to St Ignatius, ‘Act as if everything depended on you; trust as if everything depended on God’.

The Hebrew saying in the Talmud, ‘Whoever saves a life, it is as if he has saved the whole world’ also recognises the value of the individual and suggests the power that each of us holds.[6] It appears on the Yad Vashem medal for the ‘Righteous Among the Nations’. Both quotations may be interpreted as commenting on the interconnection between the singular and the whole, the individual’s potential to affect ‘everything’, ‘the whole world’.

It was a network of individuals that saved Joseph’s life.[7] Indeed, Joseph often speaks of how it was the ‘Jesuit community’ who saved him. The man who directed him to the Sacred Heart of Jesus Church may well have been a fellow Jesuit, or at the very least aware and supportive of Father Raile’s actions. Father Raile knew who to send Joseph to, who would take him in. It is known that Father Raile also cooperated with Father Ferenc Kálló and two army officers who were sheltering Jews at the Royal Hungarian 11th Garrison Hospital. When the Arrow Cross took over the hospital, these men coordinated efforts to take in Jews at the Jesuit residence, the Sophianum convent on Kalman Mikszath Square, the Marist Brothers’ school in Andrew Hogyes Street, and a boarding house run by the order of the Kalocsa Teaching Nuns on Mary Street.[8] The power of having strong connections between the individual and the community is vitally apparent.

Speaking of how he survived, Joseph says: ‘I always felt far too small to ask for favours in prayers but my father had complete trust in his conviction that God would keep his children safe. I thank God for His selection of the “right” person at the gravest moments of danger, who kept me from harm. In this spirit I recognise, with the greatest appreciation, the man who guided me to the Sacred Heart of Jesus Church. I hold a reliquary in my heart for Father Raile, the Haklik family, Bela Floris, and for the mysterious warrior who pulled me to safety just before my intended execution. This reliquary contains the most precious material in the world, created by their acts of holiness, which overcame and defied all crimes, sins and evil. Those wonderful personalities and many others who helped me, remain in my heart with blessed memory.’

Joseph’s story was told to Andrew Hadik.

[1] Kinga Frojimovics, Jewish Budapest: Monuments, Rites, History (Budapest: Central European UP, 1999), p.9.

[2] The Arrow Cross Party was a national socialist party led by Ferenc Szálasi. The name in Hungarian, Nyilaskeresztes Párt - Hungarista Mozgalom, literally mean s’Arrow Cross Party - Hungarian Movement’.

[3] Martin Gilbert, The Righteous: The Unsung Heroes of the Holocaust (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2004), p.431.

[4] Gilbert, pp.381-406.

[5] Gilbert, pp.439-442.

[6] Mishnah Sanhedrin, 4:5; Yerushalmi Talmud, 4:9; Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin, 37a.

[7] Martin Gilbert describes how often there were multiple people involved in saving one Jewish child, xx.

[8] Géza Bikfalvi, ‘The Humanitarian Rescue Activities of the Jesuits during the Holocaust', in Saving Lives in the Holocaust, edited by Zózso Hevizi, translated by Péter Csermely (Pómaz: Kráter Workshop Society, 2016), 56-65, p.59.