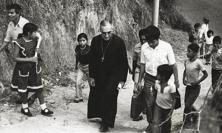

Easter Monday marks the 28th anniversary of the martyrdom of Monseñor Oscar Romero, Archbishop of San Salvador, who once said, ‘as a Christian, I do not believe in death without resurrection. If they kill me I will rise again in the people of El Salvador.’ Rodolfo Cardenal SJ writes about the legacy of Archbishop Romero – very much alive in the Church today.

Pope Benedict XVI, speaking of the foundations of the Salvadoran Church to the country's episcopal conference at the end of their ad limina visit to Rome last month, praised Archbishop Romero as a "pastor filled with love of God", committed to the preaching of the Word of God (Allocution of 28 February 2008). Here, Benedict XVI not only pays homage to the martyr bishop of El Salvador and recognises him as an exemplary pastor worthy of imitation in the preaching of the gospel and the edification of the Church - he also joins the immense majority of the Salvadoran people in their feeling for Oscar Romero, remembering him and commemorating him with genuine admiration and love. To judge from these words of Benedict XVI, it would seem that the reservations or suspicions there may have been about his episcopal ministry, his dedication to the mission of the Church and his devotion to the will of God, have at last been put to rest.

The importance of Monseñor Romero in today's El Salvador is indisputable. The almost three decades since his martyrdom have not in any way diminished his image, but rather underlined his living presence. Archbishop Romero is a key reference point of national and ecclesial life, even for those who reject him, since they cannot but recognise his importance for the country and the world. In a society disfigured by violence, massive emigration, inequality and poverty, and the social and political irresponsibility of its leaders, Oscar Romero is still a hugely significant figure. Although the historic situation of the country is not what it was thirty years ago, when he began his ministry as archbishop, his message has not lost its relevance. At that time, the country was entering a period of bloody and cruel civil war; now, social violence leaves more wounded and dead than the incipient conflict did then. Today it is a generalized violence, and the protagonists are not only the gangs of youths organized for crime and drug trafficking, but also regional and international criminal organizations, the drug traffickers and the people traffickers, and ordinary men and women from so-called ‘civil society’ who cannot resolve their differences without resorting to violence and are also responsible for this violence. Therefore, in spite of the 1992 peace accords which brought an end to the civil war, whose birth and whose consequences Monseñor Romero clearly foresaw, Salvadoran society continues to be at war with itself. It yearns for reconciliation and a lasting peace, but does not know how to achieve them. It only knows military, social, domestic and gender violence. Archbishop Romero points out some roads to reconciliation and social and personal peace, but there is no one to lead the way down these roads.

Social inequality and poverty have obliged one third of El Salvador’s population to emigrate to the countries to the north - principally the United States. The break-up of families, the distance separating those who stayed from those who left, is another disfigurement with serious consequences. A decision to leave the family and the country is not an easy one. The journey is very risky and expensive. Insertion into the country of destination is not easy. Life and work conditions are hard. The persecution of emigrants feeds fear and despair. Deportation is ignominious. Loneliness and homesickness take a hold on those who left as adults. The thousands of millions of dollars which they send to help their families is also big business for the financial and commercial sector, the very ones who by reason of their avarice force people to emigrate even today. In the anguish and suffering that these wounds provoke, Archbishop Romero stands out as an understanding and compassionate pastor, near at hand and therefore a protecting presence for those sunk in uncertainty on seeing their loved ones depart, perhaps for ever, and for those who leave for strange lands, full of dreams and uncertainties.

The government and the wealthy elites make strenuous efforts to project a successful image of El Salvador. They have turned the country into a 'brand' destined for the consumers of international tourism. El Salvador is presented, even by respected international organizations, as a model society. But the social violence, the massive emigration and the scandalous inequality in the distribution of income cast serious doubts on this 'brand'. In El Salvador today there is still massive poverty, concentrated in some rural areas. But even more than the poverty, the inequality caused by the unfair distribution of income corrodes the basic social structures. The usual poor are now joined by other sectors of society who are denied opportunities for stable employment, education, health, homes, etc. The fight for survival is so fierce that society, families and persons become dehumanised. The ferocious competition for the few available opportunities leaves to one side even the elementary principles of common living such as respect for the human person, for community life and solidarity. Salvadoran society today is very inhuman and even cruel. The repeated calls of Archbishop Romero to work for the justice of the kingdom of God and for the construction of human fraternity ring out especially strongly today. His valiant and visionary word is still able to denounce sin, call to conversion and arouse hope where frustration and disillusion predominate.

In the commemorations of Monseñor Romero the power he has to draw young people together is amazing. The archbishop’s own generation is grown up now and is disappearing bit by bit. However, the tradition begun by his ministry has now been passed on to a new generation, which has also found in him a human and gentle pastor, committed to the transformation of unjust and violent structures. Paradoxically, Oscar Romero has something important to say to today's youth, immersed as they are in a secular and technological culture. The example of his life and message reaches the inmost hearts of thousands of young people. They may not be very clear about its theological and pastoral significance, but there is no doubt that it opens up for them horizons of idealism and utopia, which the world they are immersed in cannot offer them.

The Salvadoran Church cherishes and cultivates the tradition of Archbishop Romero, and, with him, the tradition of martyrdom among priests, men and women religious and pastoral workers. Perhaps this tradition is the most valuable contribution of the Salvadoran Church to the universal Church and to the world. It witnesses to generosity and absolute trust in God. Christian base communities all over the country, with different ways of thinking and feeling, identify with Monseñor Romero and the Salvadoran martyrs. Their commemorations are calls to live the Christian faith to the end. The consecrated life, in general terms, feels challenged by the martyrs. The hierarchy, the clergy and pastoral workers find today in Oscar Romero, according to Benedict XVI, a model of how to exercise the episcopal, priestly and missionary ministry at the service of a people hungry for the Word of God, profoundly believing, showing incredible solidarity in extreme situations, and in need of having their hope strengthened.

The continuing relevance of the ministry of Archbishop Romero remains utterly intriguing. How is it that after thirty years his words are listened to with admiration and respect, his story is still heard with enormous interest, and that all this has been gathered up by tradition and national art? The answer is simple, but nonetheless profound. Monseñor Romero's strength is rooted in his fidelity to the reality of the people entrusted to his care and guidance. He did not succumb before the military, political and economic pressures to make him withdraw from what he believed to be the will of God for him. Nor did he give way to certain ecclesial pressures. He kept firm in solitude and abandonment. Not even the threats against his life were able to deflect him from his path. He made his own the suffering of the impoverished, persecuted and abandoned. He did not refuse dialogue with anyone, even with those who attacked him and insulted him. He gave them all a proof of his faith and of his love. He spoke to them all of the God of Jesus, who condemns injustice and violence, but who also offers unconditional pardon and mercy. Oscar Romero does not fade away with the passing of the years, because he was faithful to the mission of preaching the reign of God to a Salvadoran people destroyed by secular injustice and cruel violence, but also a believing people, a people in search of a utopia which would give them reasons for hope. The searing relevance of Archbishop Romero then is that of the God of Jesus, who continues to seek out a humanity unhinged by avarice and violence; but a humanity which in the end, perhaps unknowingly, also yearns for pardon and compassion.

Rodolfo Cardenal SJ is Vice-Rector of the Universidad Centroamericana José Simeon Cañas (UCA), the Jesuit-run University in San Salvador.

The 28th anniversary of the martyrdom of Archbishop Oscar Romero will be commemorated at a special Mass at Sacred Heart Church, Lauriston Street, Edinburgh on Easter Monday, 24 March 2008, at 12.30 pm. ![]() Download flyer (PDF)

Download flyer (PDF)

An ecumenical service to mark the anniversary of Monseñor Romero’s martyrdom will be hosted by St Martin-in-the-Fields Church, Trafalgar Square, London, on Saturday 29 March 2008, at 12 noon. ![]() Download flyer (PDF)

Download flyer (PDF)