Following his series on the Sunday gospel readings during Lent, which were taken this year from Luke’s Gospel, Jack Mahoney finally considers St Luke’s description of the Ascension of our Lord, which is celebrated either today or this coming Sunday, and of the Descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost.

Our series, Keeping Lent with St Luke, in which we looked at this year’s Sunday gospels during Lent, mostly taken from Luke’s Gospel, can fittingly close with considering how St Luke described the Ascension of Our Lord (Lk 24:46-53), and the sending of the Holy Spirit to his followers on the feast of Pentecost (Acts 2:1-11).

Shalom!

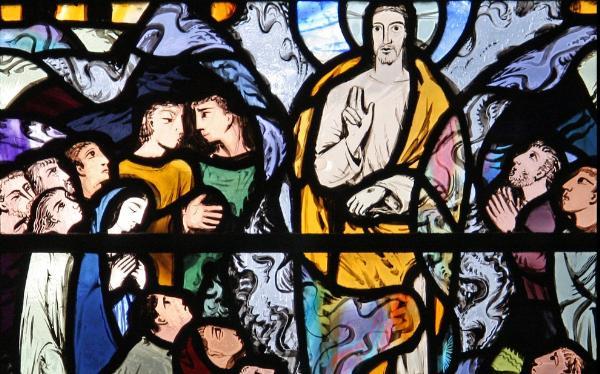

One passage we have already considered (24:34-49), in which St Luke describes the risen Lord’s appearance on the evening of his resurrection to his disciples collected in the upper room, begins with Jesus addressing his terrified disciples with the reassuring words: ‘Peace be with you.’ This was not simply the commonplace Jewish greeting, Shalom. The risen Lord was conferring on his community the benefits of his death and resurrection, the great messianic gift of peace: peace firmly established between themselves and their Father in heaven, and peace created among themselves as the newly adopted family of God. In this way Jesus not only exemplified the instruction that he gave earlier to his disciples, that when they entered a house they should wish ‘peace’ to all who were present (10:5-6). He was also now bringing the journey of Luke’s Gospel to completion by fulfilling the promise proclaimed by the angels at Bethlehem at its start: that Jesus would bring about ‘peace among those whom God favours’ (2:14).

After he had convinced his frightened disciples that he was real and not a ghost, Jesus repeated the message which had been given to the women early that morning at the empty tomb (24:1-8). He had given the same message later in the day to the disciples on the way to Emmaus (24:26-27), ‘opening their minds’ to understand that his death and resurrection as Messiah had been necessary in order to fulfil Scripture, and to make it possible for ‘repentance and forgiveness of sins to be proclaimed in his name to all nations’ (24:47). Now, however, he introduced a new note: with the words ‘you are witnesses of these things’ (24:48) he commissioned his disciples as his emissaries with the apostolic authority to preach their experience of Christ.

‘You are witnesses’ (24:48)

The conclusion of Matthew’s Gospel, which is quite independent from that of Luke, records the famous commission given by the risen Jesus to his ‘eleven disciples’ on the mountain top in Galilee: ‘All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. 19Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptising them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, 20and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you. And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age.’ (Mt 28:16-20). By contrast, the closing of Luke’s Gospel has a different purpose. It is a much less formal statement, not providing a detailed rounding off of events, because Luke plans to continue his narrative into a second volume. Moreover, he does not describe the risen Jesus and his disciples as returning north to his native Galilee, as he would have been aware Mark had done in his Gospel (Mk 16:7). Instead, he telescopes places, as it were, having Jesus remain in Jerusalem and preferring to keep our attention fixed there theologically. This was the centre of Israel to which Jesus had been drawn to fulfil his destiny, like former prophets, and it was also the point from which the early Christian Church was going to spread the message of the risen Christ throughout the world, as Luke would narrate.

In fact, we learn from Jesus in this resurrection passage that the disciples were to stay in Jerusalem until they received ‘what my Father promised’, that is, ‘until you have been clothed with power from on high’ (24:49). Jesus appears to have in mind here the prophecy that had been made about him by John the Baptist, that someone was coming who would replace John’s water baptism with ‘baptism with the Holy Spirit and with fire’ (3:16). And, indeed, Luke subsequently opens his account of the Acts of the Apostles by having Jesus explain that ‘the promise of the Father’ was that ‘you will be baptised with the Holy Spirit not many days from now’ (Acts 1:4-5).

At first reading, this appearance narrative seems to go on to describe how Jesus then led his disciples out from the upper room to Bethany for his final departure from them (24:50). However, Luke does not connect the events together, but just describes them as happening one after the other; and it is unlikely that we are intended to conclude that late in the evening of Easter Sunday Jesus would lead his followers out of the city to Bethany for a final farewell in the dark (24:50-51). This is confirmed by the opening chapter of Luke’s sequel, which tells us that after his resurrection, the risen Jesus was planning to spend more time instructing his followers, before departing from them later to return to his Father (Acts 1:1-5).

At the eventual Ascension of Jesus from Bethany (24:50-53), Luke informs us in his gospel that the apostles ‘worshipped him’, thus providing us with a final acknowledgement of Jesus’s divinity; and he describes how they ‘returned to Jerusalem with great joy’, evidently strengthened not only by his resurrection and his returning to them and by their faith in his supporting presence, but also by his formal commissioning of them now as ‘witnesses of these things’ which had to happen to the Messiah (24:48). It is then typical of Luke, and characteristic of his theology of Jerusalem and the Temple, that he concludes his narrative, for the moment, by describing that while they awaited the promised initiative of God, Jesus’s followers were ‘continually in the temple blessing God’ (24:32). The Temple was the focal point in Jerusalem which had been central to Jesus’s ministry, as we saw in reflecting on the woman taken in adultery, and the place where Luke’s whole Gospel had initially started (1:8-17) with the message of the angel to Zechariah foretelling the birth of Jesus’s forerunner, John the Baptist.

The gift of the Spirit

Opening the Acts of the Apostles, his sequel to his gospel, Luke tells us how after his crucifixion, Jesus ‘presented himself alive’ to his apostles, ‘appearing to them over the course of forty days and speaking about the kingdom of God’ until they would receive ‘the promise of the Father’, and be ‘baptised with the Holy Spirit’ (Acts 1:3-5) so they could become ‘my witnesses in Jerusalem, in all Judaea and Samaria and to the ends of the earth’ (Acts 1:8). After Jesus had formally departed from them, Luke continues, the apostles returned to the upper room ‘where they were staying’, ‘constantly devoting themselves to prayer, together with certain women, including Mary the mother of Jesus, as well as his brothers’ (Acts 1:12-14). It was while they were all together there at prayer, on the festival day of Pentecost, Luke tells us, that they received the gift of the Holy Spirit which had been promised them by Jesus and the Father, experienced like a powerful gale blasting throughout the house, and appearing as tongues of fire dividing and resting on each individual. ‘All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other languages, as the spirit gave them ability’ (Acts 2:1-4).

As so often in the Bible, what appears at first sight to be simple description can turn out to be rich with theological allusion and significance. The forty days spent by Jesus remaining with his disciples, devoted to instructing them further ‘about the kingdom of God’ (Acts 1:3), recalls, as we saw in an earlier article, the spiritual experience of his own forty days of prayer and planning before beginning his ministry, as well as the forty days spent with God by Moses and Elijah, and above all the forty years of God’s preparing the people of Israel in the wilderness of Sinai. Forty days, a period lasting some six weeks, is a sacred term in the Bible referring to time spent in God’s presence, which is still revered in Christianity in the period of Lent.

It does not seem, however, that Jesus spent all this time continuously with his disciples, as he had in his public life, but that he appeared to them from time to time. The twenty-first chapter of St John’s Gospel, describing Jesus meeting his apostles by the lakeside, provides the outstanding instance of this, but there are also suggestions that other events described in the Gospels, as we have seen, originally occurred as post-resurrection appearances, such as Jesus’s walking on the waters, even the feeding of the five thousand, and especially perhaps the scene of Peter’s impassioned confession of his sinfulness before Jesus (Lk 5:3-11), which seems to make much more sense if it occurred after his denial of Jesus (22:54-62).

The gift of the Holy Spirit being conferred on the disciples to empower them to fulfil their mission of preaching Jesus throughout the world recalls for us that, according to Luke, Jesus himself was regularly influenced by the Holy Spirit (1:35; 2:26-7; 3:22; 4:1; 4:14; 10:21; 11:13; 12:12), notably in his claim in the Nazareth synagogue that he was beginning his ministry in the very power of the Spirit (4:18-21), the consequence being that his apostles would continue his work in the Spirit. The reference to their being enabled ‘to speak in other languages,’ as the following verses in Acts describe in detail (2:5-12), provides us with a picture of how the gospel was now, under the power of the Spirit, to be preached and understood in every country throughout the world. It may also, as some Fathers suggested, refer back to the event of the tower of Babel (Gen 11:1-9), whose builders aimed at reaching up to heaven, when God punished their ambitious pride by confusing their language and creating disunity among them – an early ‘Fall’ story; the implication now being that the Holy Spirit was reversing Babel and restoring unity among God’s human creatures by introducing a common tongue of mutual love among them.

Moreover, reference to the Spirit of God being given now to Jesus’s disciples points back to the great Old Testament promises of God, that in coming Messianic times ‘a new heart I will give you, and a new spirit I will put within you’ (Ez 36:26). These were the days foretold by Jeremiah, Luke implies, that ‘are surely coming, says the Lord, when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah’ (Jer 31:31). This was to be no less than the ‘new covenant’ which Luke tells us (22:20) Jesus instituted in his blood at the Last Supper, the new covenant by which, according to Jeremiah, ‘I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people’ (Jer 31:33).

‘A law will go forth from Sion’ (Is 2:3)

There is thus an intriguing theological connection between the gift of the Holy Spirit which the Church is now celebrating and the Mosaic Law which was given by God of old to the people of Israel. In fact, the annual feast of Pentecost, the day when Luke tells us the Holy Spirit was conferred on the apostles (Acts 2:1), was the traditional celebration in Jerusalem to commemorate God’s giving of the Law to the people of Israel on the ‘fiftieth’ day (the Greek pentekosta) after they left Egypt. Some fifty days after their hasty Passover meal and their escape from the Egyptians into the wilderness, the Israelites reached Mount Sinai and camped there. It was there, we are told, in simple but breathtaking words, that ‘Moses brought the people out of the camp to meet God’ (Ex 19:17); and that God established his covenant and gave his law to the Israelites, creating them as his special chosen people and conferring the law, or Torah (instruction), on them as a charter of national identity and dignity they were to cherish (Ex 19:1-6).

The feast of Pentecost thus annually celebrated the giving of the Law, but as the Israelites came historically to show themselves disobedient to God they were dramatically punished by God’s allowing them to be expelled from their land into exile in Babylon. Their prophets, including Jeremiah and Ezekiel, as we have seen above, began to predict a time of consolation in the future when a forgiving God would confer a ‘new law’ and a ‘new covenant’ on Israel, and God’s rule would then spread through Israel to the whole world. This was all summed up in the prophecy of Isaiah that ‘a law will go forth from Sion’, that is, from Jerusalem (Is 2:3).

In his sermon at Pentecost explaining to the bewildered Israelites what was going on (Acts 2:14-16), Peter recalled another prophecy, that of Joel (2:28-32), that God was going to pour out his Spirit on all flesh. Thomas Aquinas was to sum up the whole prophetic drama of the gift of the Spirit to the early Church at Pentecost when he observed in his Summa Theologiae that ‘the feast of Pentecost was celebrated after fifty days to recall the benefit of the giving of the law’ (I-II, 102.4 ad 10), and further that ‘the feast of Pentecost in which the old law was given was succeeded by the feast of Pentecost in which “the law of the Spirit of life” (Rom 8:2) was given’ (I-II, 103, 3 ad 4).

St Paul’s reference in the Letter to the Romans to ‘the law of the Spirit of life’, quoted by Aquinas, brings together the idea of God’s new law as the gift of the Holy Spirit, as the prophets had foretold, but Aquinas added a new theological richness by clarifying that the new law is actually the Holy Spirit himself (ST I-II, 106.1 et ad 1). In true Scholastic style he examines the idea of the ‘new law’ of the Gospel and he makes a remarkable distinction between the ‘principal’ element of the new law as the very presence of the Holy Spirit in our hearts, and the ‘secondary’ element of the new law as everything which disposes us to receive that presence of the Spirit into ourselves or which then helps us express that presence in our lives. Thus the Gospels themselves, the Church, the sacramental system and the whole structure of the Christian religion are important as part of the law of the gospel, Aquinas recognised. But they are all of only ‘secondary’ importance, paling into insignificance compared with what Aquinas pointed out was the ‘principal’ element of the new law, which St Augustine described as ‘the very presence of the Holy Spirit’ within us as God’s dynamic power and influence.

The age of the Spirit

We live our lives now in the age of the Spirit of Christ, whose dynamic expansion of the Christian community throughout the Mediterranean world Luke went on to describe, sometimes in idealised terms, in his second volume, which has occasionally been more appropriately called the Acts of the Holy Spirit. With the gift of the Spirit of Christ on the Apostles at Pentecost the Christian dispensation was brought to its fullness. The Fourth Eucharistic Prayer puts it well: ‘that we might no longer live for ourselves but for him, he sent the Holy Spirit from you, Father, as his first gift to those who believe, to complete his work on earth and bring us the fullness of grace’.

The gift of the Spirit is aimed at breaking the crust of our self-concern, and opening our minds and hearts to Jesus and to one another. We are enabled in this mysterious way to share in the very inner life of God, by which the Father, his Son and their Holy Spirit perpetually communicate with each other, and invite us to be caught up into their plan to receive and share their life and mutual love as created in their image. The Spirit of God, who brooded over the earth at creation (Gen 1:2), was given at the incarnation to Jesus, the Word made flesh, to form Jesus the Christ through his life, death and resurrection into a fitting human instrument through whom the Spirit could then be communicated to his followers at Pentecost and create the Church. St Albert the Great once put it well when he observed that the Holy Spirit is ‘the first gift, in whom all other gifts are given’.

Jack Mahoney SJ is Emeritus Professor of Moral and Social Theology in the University of London and author of The Making of Moral Theology: A Study of the Roman Catholic Tradition, Oxford, 1987.

![]() Keeping Lent with Saint Luke

Keeping Lent with Saint Luke

![]() The Temptation of Jesus

The Temptation of Jesus

![]() The Transfiguration of Jesus

The Transfiguration of Jesus

![]() ‘Repent or Perish’

‘Repent or Perish’

![]() The prodigal son and his jealous brother

The prodigal son and his jealous brother

![]() The Woman Caught in Adultery

The Woman Caught in Adultery

![]() The Passion According to Saint Luke

The Passion According to Saint Luke

![]() The Resurrection According to Saint Luke

The Resurrection According to Saint Luke