Joe Egerton draws on a course he offered at the Mount Street Jesuit Centre to argue that J K Rowling has given Christians a valuable resource to introduce some of the central beliefs of the Catholic faith to a generation that knows the life of Harry Potter far better than it knows the life of Jesus Christ.

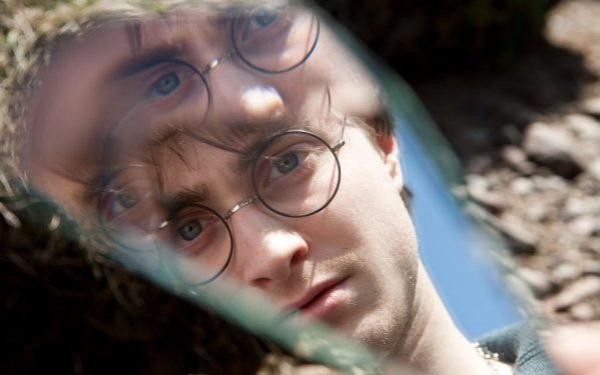

The anticipation that preceded the release of the latest Harry Potter film was a reminder that a whole generation in the UK would score higher on questions about J K Rowling’s life of Harry Potter than they would on St Matthew’s life of Jesus Christ.

The task of the re-evangelisation of these islands may not be quite as formidable as that faced by St Augustine, but it is certainly daunting. Our culture retains many older values – militant secularists did conspicuously badly in the general election, and it is interesting that when the usual suspects lined up to denounce the Papal visit, elected Parliamentarians were conspicuous only by their absence. The problem that we face in most quarters is not hostility or even indifference; it is ignorance: millions have never heard or read the story of Jesus Christ. For every one person aged under 30 who heard the Passion read last Good Friday, several hundred will go to see Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.

As St Paul showed when he spoke of the altar of the unknown God in Athens (Acts 17), and Matteo Ricci SJ showed in China when he wrote The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven, evangelisation has to start by addressing the culture as it is. Harry Potter is certainly part of our culture and I am going to argue that J K Rowling has given us an opportunity for spiritual conversation – that is, conversation about central aspects of our faith – that we should seize.

Values celebrated

J K Rowling’s novels celebrate certain virtues. Among these are constancy, courage and friendship. Love, too, plays a vital part in the story – love is the virtue that Harry Potter’s mother displays when she gives her life to save Harry and it is the absence of love that is the dominating and ultimately fatal flaw of Harry’s nemesis, Voldemort. There are a number of other themes to note in the novel: we have free will – our choices are not predetermined for us; we have to choose between good and evil; evil, as Harry is told by his teacher, Dumbledore, is the absence of or corruption of love – Voldemort has driven love from his soul; and death is not the ultimate evil, to be feared above all else.

All of this jumps from the pages of St Thomas Aquinas[1] - although it may reasonably be objected that St Thomas demonstrated that human reason can lead us to these conclusions. Dumbledore quoted Aristotle, not Aquinas, when he observed that there are many worse things in this world than death.

However, celebrating the virtues is not enough to acquire faith[2]. A philosophical approach – in contrast with the knowledge that comes from reading the life of Jesus Christ –to such questions as ‘Who am I?’ ‘Where do I come from and where am I going?’ ‘Why is there evil?’ ‘What is there after this life?’[3] requires true answers; but it is only faith that can finally give a complete answer to these questions,[4] and that is why one way of undoing the damage that has been done by a shameful failure to ensure that the story of Jesus Christ is known, may be through conversation around these questions. In embarking on such an adventure, we are of course ourselves making an act of faith, for unless the Holy Spirit gives the gift of faith, our companion will not be led to belief.

J K Rowling is of course writing novels, not theological treatises, but a novel can both ask and offer answers to important questions. Why is The Deathly Hallows a basis for ‘spiritual conversation’, that process of dialogue that leads to the truth that is Jesus Christ?

The philosophy of J K Rowling

J K Rowling gives an answer to the question, ‘who am I?’ in her account of the soul and its relationship with the body, an account that is consistent with both what is revealed initially to Israel, then expressly stated by Jesus Christ.[5]

A number of events in the novels pre-suppose some form of life after death – so a materialist account of human beings, in which we are simply entities that obey various laws of physics, chemistry and biology is ruled out. Right at the end of The Deathly Hallows we are offered something really interesting: Harry Potter gives himself voluntarily to death to save his friends as Voldemort attacks Hogwarts. When Voldemort curses him, he finds himself, with his physical body but clean and unhurt[6], in a great hall where he is joined by Dumbledore, who is unquestionably dead. There is also a maimed, unfinished creature, which is what Voldemort has made himself. This is the departure point for a journey in the next world, but not one that Harry makes, as he is still alive. This is a vision of the start of the next life – it is stated expressly to be going on in Harry’s head, but real nonetheless. J K Rowling has given us here a useful entry to discussing our belief in life after death.

She has also, in the image of the damaged soul of Voldemort, provided an illustration of the idea that one damages one’s soul by sinning and that a really bad sin does really bad damage. It is a central part of our faith that nobody is rejected by God but that we by our own choices can reject God; similarly, the significance of the powerful image of the damaged soul of Voldemort lies in that the damage was inflicted by Voldemort himself, not some avenging deity.

J K Rowling’s account is one in which repentance plays a crucial role. In The Half Blood Prince, we are told that repentance can restore the wholeness of the soul and at the end of The Deathly Hallows, Harry Potter urges Voldemort to repent. There are echoes then of the two ideas central to our Catholic understanding of how we are related to God: of free will and personal responsibility (that allows us to destroy ourselves); and of repentance – which is effective because of the sacrifice of the Cross.

This account of the soul is reinforced by a fictional device. The Horcrux – first introduced in Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince – is a fragment of a soul that if embedded in some object will guarantee immortality to the remainder of the soul. Tearing a soul apart is an extreme act of damage, and can only be achieved by murder. Taken analogically, the Horcrux provides an illustration of a dangerous belief – that our achievements in this world can obtain us immortality.

The question ‘why is there evil?’ is also addressed. In The Last Battle, the last of C S Lewis’s Narnia novels, we are offered a Manichaean account – evil (as represented by a bad god, Tash) appears to have actual existence. In Star Wars there is ‘the dark side of the force’. J K Rowling has none of this. Her account of evil – voiced by Dumbledore – is the same as that of St Thomas Aquinas. Evil is the absence or corruption of some good, an absence or corruption that typically we humans bring about for ourselves[7]. Voldemort ultimately fails because he cannot understand that. We are also taught to be careful as to what we regard as an evil - life in this world is a good and to be treated as such, but death is at the right time a friend[8].

Other passages

In The Deathly Hallows, we are introduced to ‘the resurrection stone’, a stone that can call back the dead. Harry Potter uses the stone to summon up his deceased family and friends to accompany him and give him courage as he goes to what he believes is certain death. We can see this as an analogy of the Catholic practice of appealing to the saints. We do not – cannot – call them back to earth in their physical bodies. But we can imagine how they would have dealt with a difficult situation and that can give us strength. It is much easier for us to imagine a human being than to talk to the Holy Spirit. On All Saints’ Day, we are invited to think of people we admired (for good reasons), not just canonised saints. In the Ignatian exercises we are invited to imagine ourselves in scenes in the gospels and to speak with Jesus as a friend – which is how he told us to treat him.

There are two direct quotes from the New Testament in The Deathly Hallows. The words on the grave of Dumbledore’s sister are a translation of Matthew 6:21 (‘For where your treasure is, your heart will also be there’; see also Luke 12:34). On the grave of Harry Potter’s parents the words come from St Paul, 1 Corinthians 15:26 (literally ‘It is death that is the final enemy to be cancelled out.’)[9] This perhaps provides a direct entry into a discussion of the Scriptures.[10]

Harry Potter as a basis for Spiritual Conversation

Conversion does not result from lecturing but from stimulating a curiosity that can only be answered by Jesus Christ. If a conversation leads to a conversion, it will only do so because the Holy Spirit was not just present but actively engaged.

We should be careful to approach the task of bringing our faith to others with humility, not pride. We may think of ourselves as fortunate in our faith – but we are sharply warned not to take pride in that. It may help us if we remind ourselves that most of us learned the faith because our parents paid heed to God’s command to pass the faith on. We should take such opportunities as we are given to undo the harm we have done when we have failed in the past to make others aware of the story of Jesus Christ, not just because we would thus – albeit rather late in the day – obey God’s command. Repentance requires restitution, so undoing the damage is a way back.

Pope John Paul II saw philosophy – by which he meant answering the questions we have discussed – as something that every human being can do and as a way of bridging the gap both between belief and non-belief and between faiths.[11] There is indeed, as Pope Benedict pointed out some years before his election, a danger that Harry Potter will come to occupy a place that is rightfully the Lord’s in the minds of those who do not know Jesus Christ. But that is no fault of J K Rowling or of the actors who present her work on screen. Nor is suppression or censorship of a film that thousands of Christian families will enjoy a remotely sensible response. We can take the advice of John Paul II to address a problem that his successor pointed out to us.

We have an opportunity to encourage those who have been denied knowledge of Jesus Christ to acquire it. They will acquire it in a very different way from that in which most of us gained that knowledge. This is emphatically not replacing the old story with a new story; it is using a new story to encourage the reading of the old story. The most famous conversion after that of St Paul was that of St Augustine of Hippo, brought about by a child who pointed to an Epistle and said ‘pick it up and read.’ Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows offers us an opportunity to explain the faith to a generation that has been denied the gospel, and ultimately an opportunity to encourage them to pick up and read, as St Augustine picked up and read, the story of God’s redemption of us all.

Joe Egerton is a management consultant specialising in financial services and co-founder of Ignacity.

[1] St Ignatius of Loyola – who studied the Summa in Paris – endorses Aquinas in the rules for thinking with the Church. The novels also explore the concept of ‘pure blood’ and ‘half blood’ which played an important part in the early history of the Society of Jesus. Under Ferdinand and Isabella, Moslems and Jews were given the choice between conversion and leaving Spain. Those who choose to convert were known as ‘Nuevos’. The Spanish church refused to allow the children of Nuevos to become priests – this was the doctrine of ‘purity of blood’. Ignatius of Loyola would have none of this. His refusal led to serious conflict – the Primate of Spain tried to prevent the Society establishing itself in Spain because the Jesuit accepted the descendants of Jews and Moslems even after the Regimini Bull. A generation after Ignatius’s death, the Fifth General Congregation bowed to pressure and introduced ‘purity of blood’ as a condition of membership to the fury of the few survivors of the first generation – although in practice great efforts were made to circumvent the ban.

[2] It is of course difficult to have a faith that requires treating the Torah as the law of God (as we are told it is in the New Testament) and not at least to try, however often one fails, to live out that life of virtue defined by the commandments; but countless millions of people have lived lives according to the virtues, or according to their consciences, without knowing of Jesus Christ, and Lumen Gentium firmly states that these are saved.

[3] Pope John Paul II, Fides et Ratio 9. For an excellent analysis of the encyclical see Alasdair MacIntyre God, Philosophy, Universities, A selective history of the Catholic Philosophical Tradition, chapter 18 .

[4] St Augustine argues that it is through faith in the Trinity that we re-acquire the power to reason; St Thomas Aquinas distinguishes between the theological virtues that are the gift of God and the ‘moral’ virtues that we can work out – but importantly argues that it is only because the virtues participate in the theological virtue of Charity (the redeeming Love of the Father and Son working through the office of the Holy Spirit) that they have the directedness towards good that they have. In Fides et Ratio Pope John Paul II defines the project of Catholic philosophy in such a way that the autonomy of the discipline is respected and upheld but the role of the Magisterium asserted in respect of conclusion that would claim that the questions are unanswerable or generate an answer that is incompatible with the self-revelation of God to Israel and in Jesus Christ. (See MacIntyre, op.cit.)

[5] It is an article of the Catholic faith set out in the Apostles’ Creed that there will be a bodily resurrection. Job tells us ‘in my flesh I shall see God.’ (Job 19:26) 2 Maccabees 7 tells of how the third brother tortured to death for refusing to break the law of Moses declares his belief that God will restore to him in the next world the limbs torn from him by the torturers. St Paul tells us that our mortal bodies will become as Christ’s immortal body.

[6] A Dominican contemporary of St Thomas has caused much merriment down the centuries by replying to the enquiry ‘will the entrails be resurrected?’ with ‘they will be purified’. But the consequence of denying the resurrection of the body in some way or other is to raise some real difficulties over personal identity after death and the relationship of the soul to the body in this world – see MacIntyre op cit. chapter 9 and also his later discussions of the consequences for later philosophers who abandoned Aquinas’ subtle account of the soul-body relationship.

[7] To say we bring about evil does not imply we can put it right unaided – St Anselm explained the necessity of the incarnation by arguing that as humans had brought about the fall, humans should put it right; but humans were incapable of undoing what they did; so God necessarily had to become Man so that as a human he could make the amend that humans had to make.

[8] An echo St Francis of Assisi: death in the great Canticle of the sun is called on to praise God and described as ‘a gentle friend who takes us on the road Christ himself has trod.’

[9] And Harry Potter does not understand them – Hermione has to explain where they come from. A demonstration of the opening lines of this article.

[10] Curiosity about these passages is a invitation to give the interrogator a New Testament – there is something to be said for Nicholas King’s translation (published by Kevin Mayhew) which has what is unfortunately called ‘an interactive study guide’ but is actually short notes ending with questions for reflection after each passage. The translation is a close rendering of the original Greek – so can be presented as ‘an authentic text’ to somebody who is not (yet) willing to accept the idea of canonical works.

[11] The example he gave was the respect that Lutherans gave to the great Jesuit philosopher Suarez