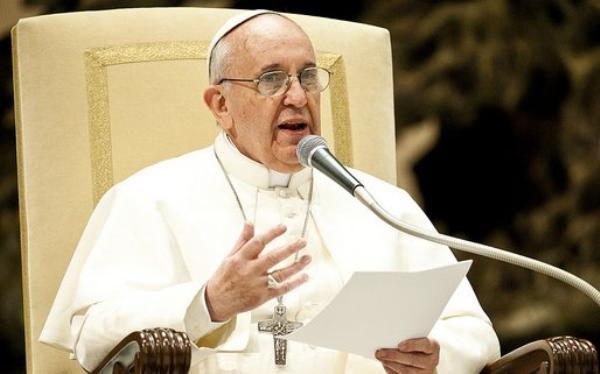

The first encyclical of Pope Francis was published on Friday 5 July. John Moffatt SJ highlights the key themes of Lumen Fidei in this guide to a document, ‘that continues a conversation with a sceptical modern audience, a conversation that Benedict XVI began and Francis is taking forward’.

Francis or Benedict?

Pope Francis acknowledges that this, the first encyclical to go out in his name, is indebted heavily to the work already done by his predecessor, Benedict XVI. ‘I have taken up his fine work and added a few contributions of my own’, he says in the introduction (§7).

Indeed, there are many hallmarks of Benedict’s style and concerns throughout. We find a close interest in the relationship between Greek and Jewish thought that gives Christianity both its intellectual language and its narrative foundations. The text is amply rooted in references to the Fathers of the Church. There are also references to modern thinkers and some familiar, delicate challenges to the assumptions of modern, post-Christian Europeans – and of modern Catholics. We also note a characteristic use of sustained metaphor throughout the work; watch out for ‘light’, ‘horizon’, ‘rock’, ‘reliability’, ‘journey’, ‘sight’ and ‘hearing’, for example.

One underlying theme is familiar from the years of Benedict XVI’s papacy: the modern world needs the Christian faith and turns its back on it at its peril. However, this is certainly not a message alien to Francis. He, too, is committed to the principle that humanity needs to know the love of God if it is to stay human. Nevertheless, in this encyclical we do find a balancing nuance – more familiar from some of Francis’ recent statements – that non-believers, too, can be seeking God in their own way (§36).

The introduction uses the voice of Nietzsche to lay down the challenge that faith, understood as a belief system, is an oppressive ideology that limits human freedom – it is a false light. In response to this challenge, the encyclical dismisses well-intentioned attempts to divorce faith from reason, attempts that lead to an individualistic or subjective faith. Reason, too, left to its own devices, eventually abandons the search for great truth, and that diminishes our humanity and we lose direction. ‘There is an urgent need, then, to see once again that faith is a light, for once the flame of faith dies out, all other lights begin to dim’ (§4).

Perhaps the richest theme, which is characteristic of both authors, is the positive message of a love of God that transforms all other loves and, out of that, all human action. And here we can notice in the encyclical a recurring emphasis that Christian belief and love lead to action that takes human suffering seriously. This was a theme of Benedict’s last encyclical, Caritas in Veritate, as well as Spe Salvi, as he responded to the criticism that Christianity does not care about human misery in this world. The urgent concern that Christians should serve the suffering poor also underpins much of Francis’ preaching.

In a sense, the precise authorship of different parts of the document is not that important. We are looking at a papal document that continues a conversation with a sceptical modern audience, a conversation that Benedict XVI began and Francis is taking forward.

Chapter 1: We have believed in love (cf. 1 John 4:16)

The title of the first chapter significantly connects ‘belief’ and ‘love’. The chapter introduces the twin ideas of the reliability of God and the trust of the man or woman of faith, encapsulated in the Hebrew root, ’emûnāh. It describes the fundamental idea of faith as personal encounter through the story of Abraham. The God who speaks to Abraham reveals himself as the source of life and meaning, and gives Abraham a horizon and a future that he otherwise would not have known.

The faith of Abraham becomes the faith of the people of Israel, mediated by the person of Moses. The theme of idolatry – the turning from God to false god – leads to a critique of the modern human condition: ‘Once man has lost the fundamental orientation which unifies his existence, he breaks down into the multiplicity of his desires’ (§13). This is certainly a claim that will provoke an interesting discussion with non-believers, and this theme is taken up again later. §14 explains how mediation does not diminish personal faith. This is an important building block in an argument that concludes at §47-49, explaining how the tradition of the Church guarantees a unity and a truth that transcends individuality.

Christ is the fulfilment of the promises made to Abraham – his death declares the utter reliability of his love, his resurrection the utter reliability of God’s word and God’s commitment to the world. In Christ we both ‘hear’ and ‘see’ something greater than our individual selves, which teaches us dependence on God’s grace rather than on our own righteousness. This changes our vision and changes our hearts. ‘Those who believe are transformed by the love to which they have opened their hearts in faith’ (§21). But again, the faith, which we must first ‘hear’, is mediated by a community, the Church.

Chapter 2: Unless you believe, you will not understand (cf. Is 7:9)

This chapter explores the connection between faith, truth and trustworthiness. Isaiah’s challenge to Ahaz to trust in God leads back to the theme of modern attitudes to truth and belief systems. In §25, the text struggles to articulate the idea that faith is the only answer to a destructive relativism because it is about the deep memory of something ‘beyond ourselves’. This glimpse into the ‘origin of all that is’ gives us a light by which to glimpse the goal and find the meaning of our common path.

This leads in turn to a more mystical meditation on the connection between faith, truth and love, and the necessity of truth in order for love to be real and constant. Further reflections show the biblical basis for faith as hearing, sight and touch, and lead to the idea that faith ‘opens us’ to the power of God’s love, to something that penetrates to the core of the human experience. Faith and reason – the search for truth – are thus deeply intertwined. Such truth cannot be the truth of an individual, yet the universal truths of faith are not oppressive, because they are truths of love and humility (§34). Here is an answer to one of the criticisms of Christian (and other) belief systems. These sections will merit close scrutiny in the conversation with non-believers who are interested in serious truth. §35 considers the journey of non-believers of goodwill as a journey of faith. The chapter concludes with a take on the relationship between theology and magisterium that is clear, though more eirenic than Pope John Paul II’s Veritatis splendor.

Chapter 3: I delivered to you what I also received (cf. 1 Cor 15:3)

This chapter builds on the social character of the transmission of faith and thus on the idea of the mediation of the Church as the living tradition. The encounter with God is mediated through Church and sacraments so that others can begin, and be sustained on. their faith journey. The assurance of faith comes not from the answers of a lonely, individual reason, but from the collective experience that takes us back to those who first encountered the risen Christ. ‘It is impossible to believe on our own’ (§39).

The chapter also develops the idea of what faith brings: an expansion of horizons into a new and enriching vision of the world and of human relationships. The faith that is communicated through the Church is more than an idea; it is ‘the new light born of an encounter with the true God, a light which touches us at the core of our being’ (§40). Meditations on the sacraments, the creed, prayer and the Decalogue affirm these as living activities of faith, the faith of personal encounter and commitment. These are, of course, the four strands of the Catechism and the chapter concludes with a reflection on the unity of faith, emphasising the need for ‘purity and integrity’ of belief – to deny one doctrine is to deny them all.

The big idea here is that there can be no separation between the doctrines of the Church and the lived faith of encounter, or between faith as personal trust in God and the doctrines that the Church asks us to hold true. This is because the tradition of the Church carries the memory of the journey so far and its magisterium gives us the assurance of truth.

Chapter 4: God prepares a city for them (cf. Heb 11:16)

The final chapter has in the background the continuing questions about the relationship between faith and society. The Letter to the Hebrews turns Abraham’s journey into the journey towards the heavenly city. Against this backdrop we find a positive apologetic for faith in society. ‘Precisely because it is linked to love, the light of faith is concretely placed at the service of justice, law and peace’ (§51). The light of faith enhances the richness of human relations, giving them trustworthiness and endurance. This is contrasted with constructing unity, ‘on the basis of utility, on a calculus of conflicting interest or of fear, but not on the goodness of living together, not on the joy which the mere presence of others can give’ (§51). There is a significant challenge here to impersonal political and economic decision-making, though people of faith do not have a monopoly on the spirit of human kindness.

In the papal tradition going back to Leo XIII, the faith-filled family is presented as the building-block of society, providing the first lessons in love, trust and openness to the action of God. This leads on to a critique of the enlightenment idea of brotherhood based on equality alone; we need the reference to the common Father. ‘Thanks to faith we have come to understand the unique dignity of each person’. And at this point we encounter a familiar Benedictine pessimism about non-Christian humanity:

Without insight into these realities [God’s love embracing all humanity, and the incarnation, death and resurrection of Jesus] there is no criterion for discerning what makes human life precious and unique. Man loses his place in the universe, he is cast adrift in nature, either renouncing his proper moral responsibility or else presuming to be a sort of absolute judge, endowed with an unlimited power to manipulate the world around him. (§54)

That this can be true is not in question; whether it has to be true is interesting material for debate.

The next paragraph is more positive, emphasising how faith can open up to a care for creation, to development that is not about utility or profit, and to government as service of the common good. An important element is the possibility of forgiveness – this arises from the assurance of faith that good is prior to evil. §55 ends with a challenge to Christians to profess their faith in public, for it illuminates life and society.

The concluding sections of the chapter consider faith and suffering, and affirm Christian solidarity with the concerns of all men and women ‘on that journey towards that city “whose architect and builder is God”’ (§57). Christian faith provides a horizon that leads us towards a greater truth and hope.

As in all encyclicals, the final section is a meditation on Mary, here as the fulfilment of the journey of faith begun by Abraham. She leads us to gaze on Christ, the incarnate Son of God.

Further conversations

This is a powerful and consoling read for committed Christians, and a vigorous encouragement to less-committed ones to open themselves again to an encounter with the liberating God of the Jewish and Christian traditions.

Not everyone will be convinced by the encyclical’s reading of Western history and of the role of Christianity in that history. However, one significant idea that runs through the text is that humanity needs the transcendent reality that we call God encountering us in our history, in order to open our horizons and to enable us to be fully human. This does provide the starting point for an important conversation with the many atheists and agnostics who are committed to a deeply ethical humanism and a better world.

John Moffatt SJ teaches Scripture at the Jesuit Institute, South Africa and is the author of the blog, Letting the Porcupine out of the Bottle.