What can a second century text about the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist tell us about care of creation today? John Moffatt SJ finds, in the writings of Irenaeus, some ideas about what it means to live in right relationship to everything of this world and be in communion with the natural order.

We sometimes see texts from the work Against the Heretics by Irenaeus, the second century Bishop of Lyons, quoted to prove the antiquity of Christian belief in the real presence. But some of those quotations are worth exploring in their wider context, because they form part of a much bigger argument. Irenaeus tells a story affirming God’s relation to the cosmos that binds the Eucharist into the goodness of the created order and the practice of social justice and care of creation.[1]

Irenaeus’s primary concern is anthropocentric, the salvation of individual humans through the death and resurrection of Christ. And that means specifically bodily resurrection and the life of the world to come. Nevertheless, his holistic depiction of the relation between creation and redemption, and therefore of the seamless nature of salvation, is still thought-provoking – particularly when we look at some of the ideas he was resisting, and recognise in them, too, some contemporary resonances.

His primary targets are various Gnostic versions of Christianity and the quasi-Gnostic theory of the Christian teacher, Marcion. The origins of Gnosticism are contested but its language and argumentation characteristically weave Platonising language in with concepts drawn from the Jewish and Jewish-Christian tradition, to form elaborate theories of the birth of the universe. These then provide a framework for a highly intellectualised narrative of salvation by knowledge (gnosis).

From the One, the serene source of all things, there emanates a sequence of cosmic beings, the last two of whom ‘sin’ and produce misbegotten and evil matter. It is left to an unfortunate demiurge (a second-order divine craftsman) to make the best of a bad job and try to turn the recalcitrant material on hand into something worthwhile. The messed-up world around us represents the best he could do. Salvation means escaping from this miserable place through a privileged knowledge granted to the chosen few, getting away from the world of matter into the world of spirit. It is a disembodied salvation for intellectual or spiritual selves who happen to be trapped in material bodies, from which they need to be freed.

Marcion offered a variant that was less extravagant in the number of cosmic beings required and used a closer reading of scripture (thus making him a more threatening adversary). The God of the Old Testament is the bad-tempered demiurge, who produces a flawed world of flawed humans reluctantly tamed by law and violence. Paul and Luke, however, proclaim the God of Jesus Christ as a loving Father, the ultimate source of reality, to whom the chosen can escape by listening to and accepting his words about love and grace. The world of the New Testament (or a sanitised version of it) must replace the world of the Old.

In all these variants, the words of Paul – ‘flesh and blood will not inherit the kingdom’ – have a challenging significance for the orthodox tradition. The doctrine of the Word incarnate is reduced to a symbol of the reality of the Word as divine messenger, in the appearance of fleshly humanity. The crucifixion is an illusion or an irrelevance. Death and bodily resurrection are an allegory for the journey of rescued souls, not realities of intra-mundane history. For there can be no union between matter and spirit. It is only in the spirit that we can be saved.

There are some modern understandings of Christianity that are not a million miles away from this, and they do not lend themselves to concern for the planet any more than ancient Gnosticism. But then we do not have to be religious to become caught up with our identity as intellectual agents ready to escape the flawed reality of our alien world as soon as we invent the warp-drive, and forget our identity as embodied beings, for whom the inescapable reality is that if we do not live in symbiosis with our environment, then we do not live at all.

When Irenaeus turns to presenting the orthodox view, it is crucial to him to affirm that the creator God of the Old Testament and the redeemer God of the New are one and the same. It is God’s spirit that pervades and guides the whole of creation. The Word of God then really entered the world made through him. He had a real fleshly body, really died and really rose, and all this so that our own embodied selves could finally enjoy the eternal life for which we were originally destined.

The Old Testament is far from irrelevant. The call to justice, the sharing of goods, a community that upholds the rights of the poor, all of which are so central to the Torah and the writings of the prophets – none of these is superseded in the New Testament. They continue to reveal the real meaning of all religious sacrifice and cult, namely, inner conversion and right living. It is only when these principles are observed that there is any point in going to the altar to offer sacrifice. Cain’s sacrifice was not acceptable to God because of his failure in communion, in sharing the goods he had received from the earth through his labour. The things of the world are valuable and its people matter in the new dispensation just as much as the old.

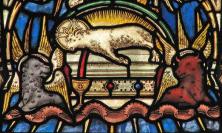

That imperative to right social communion applies just as much for a valid celebration of the Christian sacrifice of the Eucharist. And as Irenaeus begins to speak of this, he puts it into the context of creation, which entirely belongs to the God who made it and who guides it from moment to moment. We can offer him nothing that he does not already own. But what we can do is offer the first fruits of creation, as Jesus commanded us, ‘not because he needs it, but so that we may not be unfruitful or ungrateful’.[2]

The bread and the wine we offer are themselves the gifts that the Creator gives us to sustain our lives. This language of ‘nourishment’ and ‘growth’ is crucial in Irenaeus’s account of the Eucharist. The real, this-worldly nourishment through the bread and wine commutes with the real nourishment for the life beyond through the body and blood of the Lord. The work of the creator flows into the work of the redeemer, and the growth towards redemption flows through the divinely sustained growth of creation. And it is at this point that Irenaeus reproaches the Gnostic Christians who claim to celebrate the same Eucharist for their failure in logic:

How can they possibly claim that the bread over which the thanks are spoken is the body of their Lord and the cup, the cup of his blood, unless they acknowledge that he is the Son of the one who fashioned the world? That he is his Word, through whom the tree bears fruit, through whom the streams flow, and through whom the earth brings forth first the shoot, then the ear, then the full grain in the ear?[3]

And if this is so, how can they not acknowledge that the flesh can receive eternal life? Irenaeus presents a vision of continuity between our life here and the life of the world to come, in this moment where the heavenly and the earthly naturally and properly meet, in the action of the Eucharist. He makes the point more fully later:

If [our flesh] is not saved, then the Lord did not redeem us by his blood, and the cup of the Eucharist does not give us a share in his blood, nor is the bread that we break a sharing in his body. For since we are his limbs, and we are nourished through creation, and he himself provides us with this creation, causing the sun to rise and bringing the rain as he will, he acknowledges the cup, drawn from creation, as his own blood, from which he makes our own blood flow, and he affirmed that the bread, that comes from creation is his own body, from which he will make our bodies grow…[4]

How could we fail to acknowledge that these bodies of ours, Irenaeus asks, nourished by the Lord’s body and blood, are destined for eternity? Again, Irenaeus gives us a vision of death and the afterlife not as a rupture with our physical past, but as its organic completion in a new, eternal and embodied harmony.

Towards the end of the fifth book, he presents a vision of the new creation drawing heavily on imagery from Isaiah. Here (and elsewhere) he is, following Genesis 1, unashamedly anthropocentric. All the animals will be completely subject to the redeemed humans, the plants will vie with one another to provide them with more fruit.[5] The vine belongs both in this world and in the world to come, which is a recognisable, physical paradise, but renewed and liberated and in which relationships between the living creatures are restored to harmony. The new creation lies not in the intellectual construct of an unimaginable beyond, but is already glimpsed in the world of our experience. The old creation is not to be effaced as a failure; rather, it is to grow to completion as something greater.[6]

Irenaeus is not offering a programme for living in harmony with creation. After all, he lives at a time when, for all the real environmental degradation and exploitation that went into feeding the Roman Empire, most people are much closer to the land and much more aware of their vulnerability to nature’s whims. The idea of humanity’s being in a position significantly to control or subvert the natural order would be ridiculous.

Nevertheless, he does warn us against damaging narratives of creation and redemption, and offers an alternative that can spur our own reflections on what such a programme for care of creation might look like. And he gives us a vision of Eucharist as a liminal space in which communion (koinonia or ‘sharing in common’) binds us with the whole natural order, with one another and with the incarnate Word, as we are nourished on the journey to redemption.

John Moffatt SJ

[1] I’ll be drawing on passages from Adversus Haereses, IV.17–18, V. 1–2, 33–34, taking the text from Migne, Patrologia Graeca, vol. 7.

[2] AH IV, 17.5.

[3] AH IV, 18.4 (emphasis added).

[4] AH V, 2.2.

[5] AH V, 33–34.

[6] AH V, 36.1.